Zinke and Trump Are Ignoring the Public

>

This December, the federal government will hold a sale of oil and gas leases across Utah. The sale, yet to be finalized, may include hundreds of thousands of acres and several areas that conservationists would like to see protected as wilderness. Yet when it was announced last summer, the Bureau of Land Management gave the public just 15 days to comment. And when the final list comes out later this month, the public will receive only ten days to weigh in.

If you don’t think that sounds like much time, you’re not alone.

Even as Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke has made noise about returning more decision-making power over federal lands to local people and away from D.C., the Trump administration and Zinke's Interior Department have taken numerous steps to limit public input. “What we’re seeing is the virtual elimination of public participation requirements across the public lands systems,” says Bobby McEnaney, director of the Dirty Energy Project at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Changes by the administration range from a reduction in time for the public to review upcoming energy sales on federal lands to a proposal to charge Americans who protest on the D.C. Mall.

The changes have left many worried that the federal lands agencies no longer serve average Americans. “‘Public,’ for this administration, seems to be mainly, or exclusively, oil and gas and extractive industries,” says Matthew McKinney, director of the Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Policy at the University of Montana.

One of the most notable changes happened in January, when BLM leadership issued a memo to all field offices nationwide about how to conduct quarterly oil and gas lease sales. During the Obama administration, when a lease sale was announced, BLM offices held a 30-day comment period, then another 30-day protest periodonce it finalized a list of parcels for lease. BLM’s January 31 memo eliminated the first mandatory 30-day requirement, giving state offices discretion to set the time period. The memo also reduced the protest period to just ten days.

The goal, the memo said, was to “simplify and streamline the leasing process to alleviate unnecessary impediments and burdens” in the expedited offering of lands for lease, as required by federal law. But the real effect, critics say, has been to muzzle the public’s ability to scrutinize what’s happening on its lands.

Many BLM offices have chosen to hold initial comment periods but have halved them to 15 days. They’ve also taken to calling them “scoping” periods and provide little information about the proposed sales—sometimes nothing more than GPS coordinates, says Sarah Stellberg, staff attorney for Boise-based Advocates for the West. This leaves the public scrambling to find out what’s on the ground and whether drilling will cause problems, she says.

The shortened time frame means that anyone—citizens, environmentalists, or municipalities—with concerns or questions about energy development on BLM lands has to act fast. “I just worked on this controversial drilling project, and we had 700 pages of material to review,” says Dennis Willis, a resident of Carbon County, Utah, and a board member of the Nine Mile Canyon Coalition, which works to protect the eponymous canyon. “And the review period was 15 days long.” Willis’s group is a tiny nonprofit with no paid staff, so it didn’t notice that the project’s information had been posted electronically on a BLM site until the shortened review period had already begun, he says, with evident frustration.

Driving this muzzling of the public is a desire to increase energy development, says Nada Culver, senior counsel for the Wilderness Society and director of its BLM Action Center. “Anything that could slow it down or modification of locations…is just presumed to be a burden,” she says.

Some argue that rules allowing enhanced participation and protest have been “weaponized” by environmentalists. But Culver says such avenues are vital for public input. “To me, that’s democracy.”

In September, opponents struck a small blow against the administration when a federal judge temporarily stopped the BLM from implementing the shortened comment periods on future oil and gas lease sales in the habitat of the greater sage grouse. The bird, which is imperiled in the interior West, often shares sagebrush habitat with popular areas to drill. The ruling would apply to hundreds of thousands of acres in December lease sales alone, according to the Center for Biological Diversity, which is one party in a broader court case. While the preliminary injunction was limited to sage grouse habitat, the judge’s action gives hope to opponents that the BLM’s memo could be vulnerable more generally.

Erosions of public input about decisions on public lands aren’t new. They also occurred under the Obama administration, says Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER). But Ruch and other watchdogs say the trend has been accelerating in the Trump administration.

Zinke and the Trump administration have stifled public participation in other ways, critics charge. Sometimes, lands agencies are not releasing the requisite public information, Ruch says. Controversial proposals to establish cellphone service in national parks, for instance, require the National Park Service to post a notice in publications such as the Federal Register and include coverage maps. “Generally, they’re not doing it,” Ruch says. “We had to sue Grand Teton [National Park] to find out about their plans for 11 towers.” The Interior Department’s inspector general is investigating the matter.

There’s also evidence that DOI officials dismissed millions of public comments. More than 99 percent of people who commented on President Trump’s national monuments review—out of some 2.8 million comments—asked for the monuments to be left alone. Yet unredacted comments obtained by the media earlier this year showed that, in its review of the national monuments, the DOI and the Trump administration ignored this feedback and shrunk the monuments anyway.

The GOP-controlled Congress also has been taking steps to restrict public input over what happens on public lands and environmental issues. In June, Representative Liz Cheney, a Republican from Wyoming, introduced a bill that would charge a fee to a person or group that protests an oil and gas lease sale. “Currently, no fee is required, and some groups have taken advantage of the ability to file protests for free by flooding the permitting agencies with frivolous protests that have severely delayed the federal permitting process and hurt our economy in Wyoming,” Cheney said in introducing the Removing Barriers to Energy Independence Act. Cheney called the fee “nominal.” But a protest filed by several environmental groups last year would have cost $1,510 had the bill been in place, according to news site WyoFile.

Last summer, Senator John Barrasso, another Wyoming Republican, introduced an amendment to the Endangered Species Act, which Republicans badly want to change. Barrasso said his changes would “increase state and local input and improve transparency in the listing process.” But Barrasso’s bill also would limit the public’s voice in several ways, according to PEER. It would shorten to 90 days a comment period for removing federal protections of threatened and endangered species. It also would further limit what documents are available to the public under the federal Freedom of Information Act, as well as limit court challenges.

Finally, there’s the Streamlining Permitting Efficiencies in Energy Development (SPEED) Act. The act “would simplify the process of responsibly permitting the least controversial drilling operations on federal lands,” according to Congressman John Curtis, the Utah Republican who introduced it last spring.

But as Willis of the Nine Mile Canyon Coalitiontestified in Washington, D.C., earlier this year regarding the bills from Curtis and Cheney, “These bills are a pure gift to the oil and gas industry.” Willis, a former longtime BLM employee in the oil and gas leasing program, told members of Congress, “The existing process, while not as fast as some would like, is effective at engaging communities, forging cooperation and results in a western landscape we can all thrive in.”

The Secret to Happiness? Hot Springs

You May Also Like

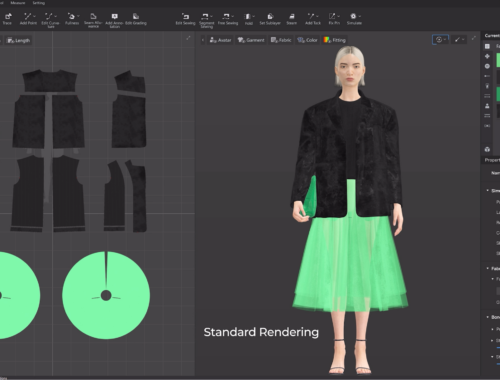

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

Wind Speed Measurement Instrument: An Essential Tool for Accurate Weather Monitoring

March 19, 2025