Your Outdoor Pursuits Make You Better at Your Job

In an era of specialization, a new study argues for diversifying your interests.

At the top of the journal Ophthalmology’s most-read list is a commentary about something called the “Temin effect” by two non-ophthalmologists: David Epstein, author of The Sports Gene, and Malcolm Gladwell, the bestselling author and podcaster. The two men, who famously tussled over the interpretation of the “10,000-hour rule” of talent development, reflect on the implications of a new study in the same journal that involved sending first-year medical students to a local museum to be trained in the art of observing art. What does that have to do with, say, the science of endurance? Well, the answer to that question is exactly what the Temin effect is all about.

The study involved 36 medical students from the University of Pennsylvania, half of whom were assigned to attend a series of six 90-minute art observation sessions at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Using a teaching framework called Artful Thinking, they were taught how to describe, observe, compare, and interpret images. The punchline: After this training, they became better medical trainees, with superior powers of observation, as assessed by blinded medical experts.

To successfully diagnose a retinal hemorrhage with a central hemorrhagic cyst, for example, the test involved noticing 18 distinct features in the image of an eye. Are there spots? Are those spots red, black, or blood-colored? Are they circular or oval? How are they distributed? Are there different shades and depths? Is there one central spot that’s larger than the others? Are there red or white lines around it?

Prior to the art training, both groups recorded a mean score of 35 or 36 on a clinical observation test. Afterward, the art-trained group scored 47.9, while the control group got worse, scoring just 30.4. (It may be, the authors speculate, that the control group was less motivated the second time around because they didn’t get the art training. Or, they add, “the initial medical school curriculum, with its intense focus on mastering the biological and molecular foundations of medicine, may actually inhibit the development of good observational skills.”)

It’s a neat finding. But to Epstein and Gladwell (who, full disclosure, wrote the foreword for my new book), its implications aren’t limited to med students. They named their effect in honor of Howard Temin, a biologist with famously broad interests who shared a Nobel Prize for his dogma-altering discovery of an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. Temin, they point out, wasn’t alone among Nobelists in his intellectual promiscuity. According to an analysis of the biographies of all Nobel laureates between 1901 and 2005, prizewinners are far more likely to engage in serious arts-related hobbies than other scientists or the general public and to have more of these hobbies. In fact, they’re ten times more likely to have this type of hobby than the eminent scientists inducted into the National Academy or Royal Society and 29 times more likely than the general public.

There are two contrasting ideas that I think are worth taking away from this discussion. One is that the hours you spend hiking through the mountains or honing your front crawl have value beyond the merely physical, and perhaps even beyond the emotional or spiritual. Sure, wilderness appreciation is not on the curriculum at fine arts schools, but I think the parallels are strong. The lessons you learn and the perspectives you gain from outdoor hobbies inevitably inform your approach to challenges in other areas of your life. Running a marathon or climbing a peak will make you a better scientist or businessperson.

On the flip side, in your pursuit of mastery in whatever hobby you’ve chosen, a narrower focus isn’t always better. Sometimes, to be a better runner, you need to get on the bike. Or, like Roger Bannister did amid the tumult of his final preparations for an assault on the four-minute-mile barrier in 1954, head to the mountains:

Chris Brasher and I drove up to Scotland overnight for a few days’ climbing. We turned into the Pass of Glencoe as the sun crept above the horizon at dawn. A misty curtain drew back from the mountains and the “sun’s sleepless eye” cast a fresh cold light on the world. The air was calm and fragrant, and the colors of sunrise were mirrored in peaty pools on the moor. Soon the sun was up and we were off climbing. The weekend was a complete mental and physical change. It probably did us more harm than good physically. We climbed hard for the four days we were there, using the wrong muscles in slow and jerking movements…

After three days our minds turned to running again…We had slept little, our meals had been irregular. But when we tried to run those quarter-miles again, the time came down to 59 seconds!

Less than three weeks later, Bannister became the first person to run a sub-four-minute mile. Call it the Temin effect.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available! For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.

You May Also Like

AI in Fashion: Redefining Creativity, Efficiency, and Sustainability in the Industry

February 28, 2025

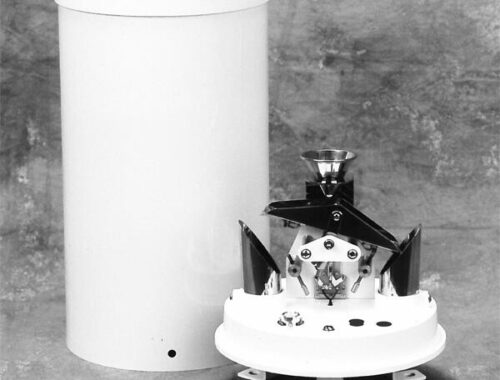

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025