Your Guide to Layering This Spring

>

Spring: The wettest and most unpredictable of seasons. How should you dress? Fortunately for you, the basic approach is the same whether you’re backpacking, skiing, or just commuting to work.

You read Outside, and you recreate outdoors, so you know this already. But just to make sure we’re all on the same page, let’s recap: Base layers keep you dry, midlayers provide insulation, and outer layers keep out the weather. Mixing up the three and stripping some of them off allows you to stay comfortable across varying weather conditions and through different levels of exertion.

Let’s say it’s 40 degrees and misty. If you’re standing still, you’ll want base layers, a warm midlayer, and a water-resistant shell. If you’re running, you might just want the base layers and shell. If the rain stops, you might want to ditch the shell. Carrying all three and tailoring them to your environment is the key to staying comfortable no matter what you’re doing or what the weather throws at you.

This approach applies no matter the occasion. Obviously your clothes will look a little different if you’re going mountain climbing instead of having a (cold) night on the town, but you should approach both challenges the same way. Here’s how.

The base layer’s job is to wick moisture away from your skin, spread it out, and allow it to evaporate. It also provides a little warmth. Think of base layers as your foundation for cold-weather layering.

Base layers can be made from a few different materials. Let’s look at the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Polyester

- Cheap (There’s no need to buy fancy layers—the Army surplus polypropylene stuff is just as good as anything more expensive.)

- Warm

- Wicking

- Stink horrendously after one wear

- Always warm (Don’t plan to wear these layers inside a hot building or during exercise.)

Silk

- High warmth-to-thickness ratio

- Can be layered even under skin-tight jeans

- Comfy

- Not warm when wet

- Expensive

Merino Wool

- Comfortable across a wide temperature range

- Can be worn for days without stink

- Warm even when soaking wet

- Wicking

- Expensive

- Some people find merino itchy

- Higher care requirements

Cotton

- Cheap

- Comfortable

- Will literally kill you if you get them wet. Literally. Kill. You. Dead.

- Please never wear cotton outdoors.

- See above.

Since we’re talking spring, which means higher activity levels in less-frigid conditions, the obvious takeaway here is that you should be wearing thin merino base layers (and matching socks, duh); 150-weight is about right. Brands like Smartwool and Icebreaker have great options for both men and women. Silk is a good option around town—it works especially well under jeans and as sock and glove liners. Synthetic is best kept for frigid winter conditions and low-output activities.

As the season progresses and temperatures rise, I’ll often wear an ultralight merino T-shirt as my top base layer and either a 150-weight merino base layer on my lower half or none at all, depending on what I’m doing. Especially for days with cold mornings and warm afternoons, this allows you strip down most effectively as temperatures rise or you enter warm buildings. Trew makes great T-shirts from NuYarn, a merino fabric that’s more durable.

Insulation. The thicker it is, the warmer it is. You can (and likely do) wear more than one midlayer. These are your wool sweaters, your fleeces, your puffy vests, and your down jackets.

Wool

- Warm when wet

- Often thin, making layering easy

- Lots of styles and varieties; can look good in any environment

- Resists light rain

- Lasts forever

- Warmth-to-weight skews heavy

- Can be expensive

- Moths eat it

Puffy Synthetic

- Affordable

- Lots of varieties; can be tailored for specific conditions if you do your homework

- Handles wet conditions better than down

- Heavier and less packable than down

- Most varieties don’t last more than a few seasons

Fleece

- Breathable

- Comfortable

- Downright cheap

- Resists light rain; doesn’t soak up water when submerged

- Limited warmth

- Lightweight, but not very packable

Down

- Greatest warmth-to-weight and packed-size ratio

- Most down jackets are finished in weather-resistant fabrics or coatings, so they can be pressed into soft-shell duties if needed

- Breathable

- Lasts for years and years

- Expensive

- Loses loft, and therefore insulation, when wet (Modern down treatments limit this effect.)

- You’ll need to do your homework to find the best values and performance.

There is just a ton of variety in midlayers. A heavy wool zip-up with a high neck might be all you need, or a lightweight, close-fitting crewneck might work great under a down jacket or vest for added warmth. Puffies are the warmest and most packable option. Fleeces layer well and are all-day comfortable across a variety of conditions. Learning what works best for you will be a case of gaining experience and utilizing what you already have in your closet.

This is also where you can find most of the variability you’ll need for spring conditions. Two thin midlayers—a wool crewneck and an ultralight down sweater—often work better than a single, heavier layer because they’ll be very warm when combined and provide you progressively less insulation as you strip down.

One item everyone will appreciate in spring is a good puffy jacket. They pack so small and so light that there’s virtually no penalty for throwing one into your pack or even a cargo pocket on your pants. And if conditions do turn for the worse, having a puffy with you is just the best insurance you can have. I’ve been wearing Patagonia’s new Micro Puff for a few months now. It’s filled with a new synthetic insulation that took Patagonia ten years to develop. It’s just as light, packable, and warm as down and should last just as long, but it also stays warm when wet and is more ethical than most down sources. That insulation is housed in an ultralight Pertex Quantum shell that breathes well but is wind and water resistant. This combination of the latest insulation with the best possible shell fabric is a winner.

Go back to that description of base layers where I explain that they wick away sweat and facilitate its evaporation. Extrapolate that process as the water vapor moves out of the rest of your clothing, and you can see why allowing water to escape is as important as keeping it from getting in. Which brings us to outer layers.

Soft Shells

- Extremely breathable

- Stretchy, quiet, and comfortable

- Affordable

- Not waterproof

- Waterproof

- Less breathable

- Often noisy

- Expensive

In everything but steady rain, you’ll benefit from being in a water- and wind-resistant yet breathable soft shell. With the stretch, breathability, and softness, they’re just that much more comfortable. Having said that, there’s no beating a proper hard shell in a rainstorm, and recent advances in waterproof-breathable technology are making them more comfortable to wear.

The most breathable waterproof-breathable membrane out there is Polartec NeoShell, which also features four-way stretch. My all-time favorite hard shell, the Westcomb Apoc, is made using that membrane and is a great technical option for skiing, backpacking, and other mountain activities. The brand makes two women’s jackets with that membrane. Filson just released a more casually styled men’s option made from it that has a heavier, stretchier face fabric, fits athletic bodies extremely well, and will be ideal for hunting, fishing, or just wearing around town. Also of note is The North Face’s Apex Flex range, which employs a soft, stretchy face fabric that feels like a soft shell but works like a hard shell. Several jackets in the line are made from the material, all of which work, look, and feel great. Just note that Apex Flex is pretty heavy—you probably don’t want to haul it along on a human-powered overnighter.

Want the function of a waterproof-breathable jacket in a less technical-looking package? Don’t get scared off by the cotton in waxed cotton—the wax fills the fibers, rendering them waterproof, while the microscopic gaps between threads are rendered too small for water droplets to pass through, but are large enough for water vapor to escape. Fjällräven, Barbour, and American firm Vanson all make excellent options.

Most technical outdoor pants can be considered soft shells and are fine for anything up to hard, persistent rain. Virtually every outdoor brand makes a range of pants. Pick the ones that fit you well and are designed for the activities you enjoy. The Fjällräven Kebs remain my favorite option for both men and women.

If you do need a hard shell for very rainy days spent outdoors, then you’ll be best served by an overpant that won’t soak up any water and that you can strip off once the storm finishes. The Marmot Precip is a good, affordable option, or if you’re really on a budget, Frog Togs.

Even if you’re staying in town, you’ll benefit from jeans with a hydrophobic coating and fabrics designed to shed water. I wear Patagonia’s Performance Jeans, which benefit from a healthy amount of stretch, helping them fit them over base layers.

On Monday, I’m taking off on a backpacking trip that will see daytime temperatures reach 70 degrees, nighttime temps into the 30s (if not colder), and possibly heavy rain from an inbound atmospheric river. The final day involves a 6,000-foot climb. I’ll be in the gear detailed above: 150-weight merino base layers, the Trew ultralight merino T-shirt, the Patagonia Micro Puff, the Westcomb Apoc, and the Fjällräven Kebs. I’m not taking any other clothing at all, but I know with totally surety that I’ll be comfortable the whole time. I just hope the first-timer tagging along will be, too.

You May Also Like

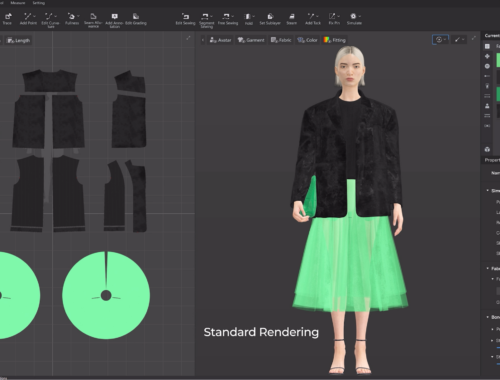

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

Escape Road: A Journey to Freedom

March 21, 2025