Why These Guys Slacklined Across the Mexico-U.S. Border

>

On January 25, the last day of the government shutdown as politicians played a game of tug-o-war over President Trump’s demand for a border wall, Corbin Kunst was on a rope strung between Mexico and the United States. The 27-year-old ropes-course technician from Petaluma, California, balanced on a slackline connecting Big Bend National Park with the Mexican Parque Nacional Cañon de Santa Elena, hundreds of feet above the Rio Grande. His friend, 26-year-old Bend, Oregon-based filmmaker Kylor Melton, directed the filming of this feat. On Monday, the team released this footage, a trailer for a longer film about the highline to come out soon.

In addition to Kunst and Melton, the team included several other Americans and Mexican nationals, including one more slackliner, Jamie Marrufo, who also completed the walk between the two countries. We had questions about the project, so we caught up with the young duo.

CORBIN KUNST: I first saw a picture of the canyon, Santa Elena, a couple of years ago actually, and it was always kind of a pipe dream. I thought, "How cool would it be to break this epic highline over the Rio Grande and it connecting two countries?" From the beginning the idea was to always have a Mexican team and a U.S. team working together and have that harmony—have it be this symbol of trust. When you rig a highline, you're literally putting your life in your team’s hands. I always thought that would be really beautiful, simple, and a really powerful project. As things developed in our current times—tension with Mexico politically going as far as it’s gone—I told my idea to Kylor.

KYLOR MELTON: This was like three weeks ago. Corbin hit me up with this idea and was like, "Hey, I have this super distant idea that I'm thinking about doing." And I was like, "Bro, can you be at my house tomorrow?"

CK: The Mexican team rigged their anchor and we rigged our anchor and it was completely up to them. I know everyone on the Mexican team, and I helped form that team. I already had trust in them—I knew that they knew what they were doing. No one had to guide them or guide us. We just kind of split up and worked together, which is really cool.

So, we threw a tagline, which is just a thin piece of paracord, and strung each side down into the river and a team member connected the two lines at the river. That tagline goes up and then the actual slackline is fed across that. I think that trust is a very powerful message. It about us coming together, working together, on all those levels.

KM: The trust is inherent. The message is that we wanted to come together. Be two groups of people coming together to accomplish and stand for what they believe.

KM: Our team consisted of friends. We had a small group—I think there was five of us on our side.

CK: Including filmmakers.

KM: So our side was pretty small. The Mexican side was something like six people. From all across Mexico, Chihuahua, Mexico City …

CK: … Monterrey …

KM: … There was like a really diverse group of friends there. We had a filmmaker on the Mexican side that was helping document that part of the story.

KM: So our laser pro-pointer broke somehow, but, if we had to gauge, about 100 meters long.

CK: We're estimating that we were about 400-plus feet from the canyon floor. This wasn't your average slackline walk because we were filming, but if we were just walking across it, it only takes a few minutes.

KM: It’s like a 100 meters, so you could walk that in 45 seconds. Not on the highline, like on the ground—highlining takes a little bit longer. But they crushed this line. I don't even think they fell. I mean they fell like once or twice.

CK: Highlining is actually a very safe sport—we were always tethered to the line. Just like in rock climbing—how most people are using protection, very few people in the sport free solo—it’s the same thing in slacklining. So free soloing is not what highlining is all about. Most the time when we highline, we're tethered.

CK: I don't like thinking of it as a stunt. It was much more than that. I mean for me it was the most important slackline I have ever walked. It had so much power in it. That so many people came together and wanted to do this idea with me. The idea wouldn't have gone anywhere unless people also felt that this was a powerful message. So, for me, as I was walking the line, that's what was going on in my head the whole time. Everything in my whole life had led up to that point of people trusting me and trusting this idea and believing in it enough to actually show up and do this. After I finished, I was pretty blitzed out. I was ecstatic.

KM: You only need permits to film in the park if your doing a commercial shoot and by all standards this is a passion project, right now. So we didn't have a permit, and the government was shut down so even if we tried to get a permit, we wouldn't get one because there were no resources to accept, acknowledge, or give us a permit. Also, the drone itself was all flown from the Mexican side. It's an interesting area. The government says as long as you’re outside the park boundaries, they don't have any control. So you can be on the border and fly into a national park.

CK: We did everything, to our knowledge, legally. The fact that the Mexican team rigged their own anchors, we rigged our anchors, we floated down the river with a river permit. Everyone that goes down the river is basically taking the same risk as we were. We were on a river trip. We did the slackline. All of us are proficient riggers and I talked to a lot of lawyers, attorneys, before the project to make sure we were actually doing everything legally.

KM: It may not be perceived as safe—you hundreds of feet up, dangling on a wire—but there's actually very few injuries, deaths or anything like that in highlining.

CK: On the U.S. side, we were not allowed to bolt.

KM: Bolting meaning drilling hole…

CK: … And put a bolt in and a hanger and rig off those bolts, which is very common in rock climbing and slacklining.

KM: But we did not do that.

CK: We respected the park's rules by rigging it naturally. So I just literally slung massive boulders with a rope. In that way, we were trying to do our due diligence of respecting the park's rules. They bolted on the Mexican side and there's no rules against that in the Santa Elena National Park.

KM: In every way we respected the laws and regulations. This isn't about disrespecting those laws, this isn't about fighting a war with Trump, this is about people coming together. These people from different lands to tell a story of bringing people together rather than separating us with that fear-based division mindset.

KM: That’s a good question. Right now I am deep, deep in the editing cave cranking away at it. I’m doing everything in my power to essentially channel energy behind this idea, to get eyes on it, and to begin to have people care about it. I'm hoping I’ll have this film ready very soon.

CK: Something that I would like to add is we also want to give voice to our Mexican friends, who were the whole other half of the team. The more and more that we reveal of this story, the more it's going to be in Spanish. We want that perspective shown too. We want this to inspire people and be a catalyst for conversation about bringing people together. I know people are going to start getting political and being like, "Oh, why are you trying to divide us? Why are you trying to put out a political video? Why are you trying to polarize us?" And I really want to bring it back to the fact that this was was a Mexican team consenting with an American team to come together to be one team. This is us being a symbol and connecting, and learning about each other, having a cultural exchange using our passion of slacklining as that medium. We want to show others, "What are you doing with your life to build bridges?”

For updates on the project, sign up for a newsletter on Melton’s website.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

You May Also Like

トレーラーハウスで叶える自由な暮らし

March 17, 2025

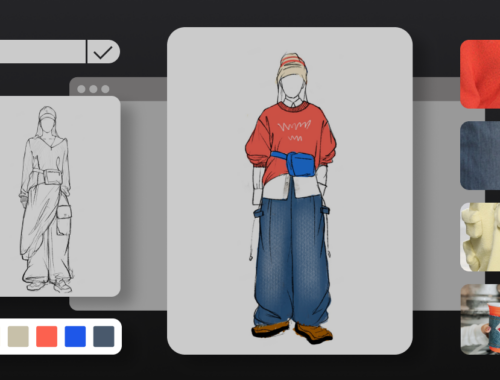

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025