Why the CDC changed its Covid-19 quarantine guidelines

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested on Wednesday that some people who have been exposed to Covid-19 can quarantine for less than two weeks.

The agency said a 14-day quarantine, in which people stay home and avoid interacting with others, is still the safest option if they come into close contact — within 6 feet for at least 15 minutes — with someone who has Covid-19. Anyone who actually contracts the disease should self-isolate until at least 10 days after symptoms begin, and not leave isolation until their fever is gone for at least 24 hours.

But the CDC updated its guidelines — which are recommendations, not legal requirements — to offer “alternatives.” People who’ve been in close contact with someone with Covid-19 should still quarantine. But that quarantine can end after 10 days without a coronavirus test. Or it can last seven days if someone obtains a negative test result, which they’re advised to get as early as day five of quarantine. People should watch out for symptoms for 14 days after quarantine.

Public health experts described the change as a harm reduction move: It’s not ideal for people to cut their quarantine time short. But if the change lets more people quarantine for some period of time, that could be better overall.

“The new guidelines are an example of a harm reduction approach, or one that takes into account the challenges individuals might face in reducing risks,” Jen Kates, director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told me. “My main concern, however, is about potential confusion, and the need for strong, clear messaging. CDC is still recommending 14-day quarantine — that should not be lost here.”

The CDC hinted at that, citing the possibilities of “economic hardship” and “stress on the public health system” due to 14-day quarantines.

“CDC continues to endorse quarantine for 14 days and recognizes that any quarantine shorter than 14 days balances reduced burden against a small possibility of spreading the virus,” the agency said.

The incubation period for Covid-19 can be up to two weeks — perhaps even longer in rare cases — suggesting that people can’t say they’re fully in the clear until a 14-day quarantine is up.

But for most people, the incubation period is now believed to be “skewed toward the shorter end of that” 14-day window, Harvard epidemiologist William Hanage said. So most people likely can cut their quarantine time short without posing a risk to others.

The change comes at a particularly calamitous time. Cases in the US are continuing to rise, regularly breaking records. Hospitalizations surpassed 100,000 for the first time this week. The daily death toll is now regularly above 2,000 — levels of death not seen since the initial spring outbreaks.

And things are bound to get worse. Thanks to the virus’s incubation period, and the fact that most people are sick for potentially weeks before hospitalization or death, we still haven’t seen the effects of Thanksgiving gatherings last week. The US could have record-breaking levels of Covid-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, right as people go on to gather for Christmas and New Year’s — further spreading the virus in sustained, intimate settings. Meanwhile, a vaccine is likely still months away for most Americans.

The CDC’s new quarantine guidance is an attempt to get Americans to do something, even as many of them resist taking the other steps the agency has called for. If it works, it could help combat just how bad things get in the next few weeks.

The shortened quarantine time is all about harm reduction

In public health, “harm reduction” means acknowledging that people are going to take risks, but still trying to make their behavior as safe as possible. People could eliminate their risk of sexually transmitted infections, for example, by never having sex at all — but given that people are going to have sex, public health officials try to encourage people to do it safely, by using condoms and having fewer partners.

As we’ve gotten more evidence on how the coronavirus spreads, and as the public has become fatigued with the pandemic and more resistant to tougher measures, health officials have increasingly taken a harm reduction approach to fighting Covid-19.

“While we might like to imagine we can instantaneously halt all transmission, in reality we are working to prevent as much as possible, which can sometimes involve trade-offs,” Hanage said.

While it’s better if people from different households don’t socialize — since any interaction carries a risk of transmission — officials have tried to push people toward safer interactions in outdoor environments where the virus can’t spread as easily. The same impulse drives the push to wear masks: Maybe people shouldn’t get their hair cut at all if they want to eliminate the risk of Covid-19, but if they’re going to, they can at least mitigate the risk of transmission with masks.

At a press conference announcing the new recommendations, CDC officials were clear that they would still prefer people quarantine for a full 14 days after exposure. But given the constraints people can face, including the need to work, and the more recent evidence that the incubation period may not be two weeks for most people, the CDC is now trying to offer some flexibility.

“We can safely reduce the length of quarantine, but accepting that there is a small residual risk that a person who is leaving quarantine early could transmit to someone else if they became infected,” John Brooks, chief medical officer for the CDC’s Covid-19 response, said.

It’s not perfect. With the CDC’s new guidance, some coronavirus infections will likely sneak through that could have been prevented by a 14-day quarantine. But if the guidance stops more infections overall by getting more people to quarantine, even for a less-than-perfect amount of time, that’s still a net benefit in reducing transmission.

This is, in other words, about striking a balance between the ideal steps to stop Covid-19 and people’s willingness to actually follow those steps.

There are still risks with a shortened quarantine

A big risk with the CDC’s guidance is there’s still a lot we don’t know about Covid-19. We’re still learning a lot of the basics about the coronavirus and the disease it causes, from how long incubation lasts to the wide range of symptoms to its long-term effects. It’s still not certain how much transmission is driven by people who never experience symptoms, and that could pose a challenge for the CDC’s guidance if it turns out a lot of people leave their quarantine early — at the new 10-day cutoff, for example — but are able to spread the virus, unknowingly, to others.

On the other hand, there are also studies showing that people may not be infectious for as long as previously thought. So it could turn out that the CDC’s new guidance is too lax, just like it could also be that the agency’s guidelines are still generally too strict.

Some experts were critical about the CDC’s guidance, calling for more clarity or tweaks to the recommendations. Saskia Popescu, an infectious disease epidemiologist, told me she’s concerned that the agency said people can get a test as early as day five of quarantine and use test results to stop quarantining after day seven. “I would’ve liked to see testing on day six or seven and then end of quarantine when the result comes back negative,” Popescu said.

Still, experts were overall receptive to the change, with Popescu noting that “it can help get more compliance for quarantine.” But, she cautioned, the CDC and other officials should be clear about the limitations and a continued need for other steps, like social distancing when possible and masking.

The big risk, for now, is the US is still in the middle of a massive Covid-19 outbreak — one of the worst in the world. In that environment, every single interaction outside of your home is a potential risk for transmission. There’s simply too much virus out there, making it easy for people to spread it.

Despite these circumstances, public health officials have also had to wrestle with the fact that people aren’t listening. For weeks, experts and officials were advising people not to travel for Thanksgiving. Then the country set records for pandemic-era airline travel last week.

The same now seems likely to happen again with Christmas and New Year’s, bringing new superspreading events as the country deals with record highs for cases, hospitalizations, and deaths.

Given that reality, the CDC is trying to meet people where they are: If individuals are going to do things officials prefer they don’t do, they can at least take some measures — even a reduced quarantine time period — to help slow spread as much as possible. It’s not perfect, but it’s where the country is at.

You May Also Like

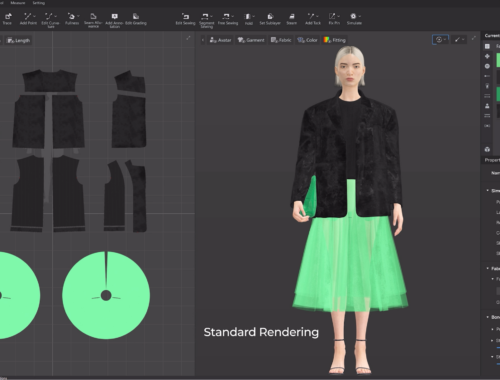

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

トレーラーハウスで叶える自由な暮らし

March 17, 2025