Why Runners Are Obsessed with Time Barriers

They might seem arbitrary, but benchmarks help define the sport

For fans of U.S. track and field, one of the more crushing moments in recent memory came during the men’s steeplechase at the 2015 Paris Diamond League meet. After outkicking Kenyan Jairus Birech for most of the final lap of the race, Evan Jager was a few strides away from becoming the first American to win a Diamond League steeple. What’s more, Jager looked poised to dip under the magic eight-minute barrier—a feat only 11 men have accomplished to date. You can probably see where this is going.

Alas, after clipping the last hurdle on the home straight, Jager landed awkwardly and tumbled onto the track. Birech, who surely thought that he’d been beat, motored past for the win. Despite his fall, Jager ended up improving his own American steeplechase record. His time was eight minutes, and .45 seconds. Bummer.

“There are so many things that define our sport: whether you can break ten seconds in the 100-meters; if you can break thirteen [minutes] in the 5K; if you can break eight in the steeple,” a dejected Jager said afterwards in an interview with the IAAF. “Being one-hundredth of a second on one side, versus the other, shouldn’t make as big a difference … but it does.”

In competitive running, performance is always quantifiable—especially on the track, where variables in course profile don’t apply. It’s an aspect of the sport that can be either uplifting or oppressive. After all, if Jager had run half a second faster in Paris and come home in under eight minutes, his loss would probably have felt like a triumph. Instead, it was all the more devastating. Why, one might wonder, do such seemingly arbitrary benchmarks carry so much weight?

One answer is that they aren’t really arbitrary at all. As Jager says, there are certain milestones that define professional track and field. For the few individuals who manage to achieve them, such accomplishments can mean everything.

“My career has taken me all over the world,” the Canadian runner and 3:52 miler Nathan Brannen recently wrote. “But to this day, only 1,497 humans have ever broken four minutes in the mile, compared to 4,638 who have summited Mount Everest during the same decades.”

As it happens, the newly retired mid-distance runner Nick Symmonds has just stated his ambition to become the first sub four-minute miler to also summit the world’s tallest mountain. His website puts it with characteristic modesty: “Love him or hate him, Nick Symmonds is the perfect person to do the impossible, make history, and close the loop on the Bannister-Hillary saga that began nearly 70 years ago.”

Most people, I’m guessing, will have been unaware that the Bannister-Hillary saga was a loop that needed closing. But Symmonds has always had a knack for this kind of self-mythologizing and, to be honest, his former profession could take an example. Professional track and field, as fans have lamented ad nauseam, needs to find more compelling narratives. Celebrating the significance of certain performances is one way to do it.

Case in point: Last year, in an op-ed for Outside, Oiselle CEO Sally Bergesen wrote that women’s track and field needed its own equivalent of a four-minute mile and suggested that a 4:30-mile might fit the bill. Elevating a specific benchmark, Bergesen argued, would be a way to enhance the tradition of women’s track since, as Bergesen writes, “milestones and lore give sports fans and participants something to look toward, celebrate, talk about, and even shoot for.”

Unsurprisingly, the allure of specific milestones isn’t limited to elite runners: a 2014 study with a data set of over nine million marathon finishing times found that there was “significant bunching” around round numbers—e.g. 3:00, 3:30, 4:00, and so on. Even more tellingly, the study found that runners who were very close to sneaking in under a round time barrier tended to slow down less in the final two kilometers of the marathon than other finishers.

On the elite end of the spectrum, a potential downside is that an excessive emphasis on race times can detract from the excitement of a strategic (read: slow) race. In the worst case, it may even incentivize doping. These are legitimate concerns. Nevertheless, it’s difficult to overstate the appeal of having a clear objective on race-day.

“It’s no wonder time goals are attractive to runners,” Lauren Fleshman, a multiple USATF national champion in the 5,000-meters with a PR of 14:58, wrote in an email. “They’re specific. It’s easy to know when you’ve accomplished them, or not. And while you can certainly make it a team effort, you don’t have to report to or rely on anyone but yourself if that’s what you crave. This doesn’t exist in a lot of people’s jobs. Or lives. The simplicity is intoxicating.”

More than anything, I think that’s what is so enticing about the pursuit of the sub 4:30-mile, or the sub eight-minute steeple, or, for that matter, any time goal to which recreational runners may apply themselves. As others have noted, it’s a rare luxury to have such clarity about what constitutes success. Regardless whether you’re aspiring to run a sub four-hour marathon or a sub four-minute mile, you’ll always know where you stand.

As for Evan Jager, he hopes to finally knock the sub eight-minute steeplechase monkey off his back at the Herculis Diamond League meet in Monaco later on Friday. The setup for the race looks promising, as Olympic gold medalist Conseslus Kipruto has stated his intention to go after the world record, which currently stands at 7:53:63. If Jager can hang on until the last lap, he should be in a good position to put Paris behind him once and for all.

You May Also Like

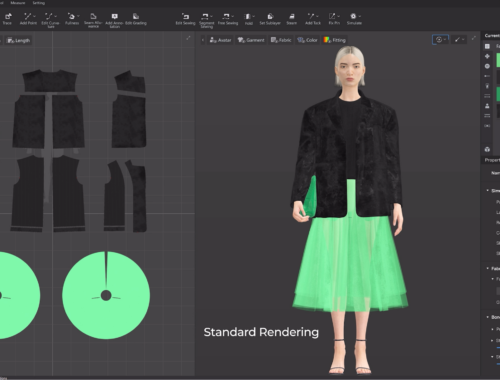

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025

Escape Road: A Journey to Freedom

March 21, 2025