Why People Go Out Of Their Way To Mispronounce My 'Foreign-Sounding' Name

“It’s pronounced Nan-DIH-nee,” I tell him. I’m sitting across from a client in my counselling office. He looks away, shaking his head. As he turns back, he repeats “nan-DEE-nee,” then tells me how people in my country live in poverty because of earthquakes and government corruption. As a counsellor, what else can I do but tolerate his ignorance?

When you have a non-English sounding name, it’s virtually impossible to avoid having someone mispronounce it. Often at issue are power dynamics which put marginalized people in the position of having to defend an important part of their identity. Along with Canada, the U.S. has a history of forced assimilation, imposing Anglicized names upon Indigenous and Black people. Even today newcomers must decide whether to adopt an English name or truncate their name. East Asian and Eastern European immigrants have experienced pressure to Canadianize their names upon entering school or applying for jobs.

Sometimes I imagine having a name that people can say without hesitation is like winning the lottery. When I have to correct someone, I usually face one of four reactions:

“I’m sorry, how do you say it?”

“That’s an unusual name.”

“How about I just call you, ‘Nan?’” or “That’s not the way it’s pronounced back home.”

I appreciate the first reaction from people who don’t get defensive and are willing to learn. It gives me a chance to correct them and perhaps share that Nandini is a Hindi derivation of my dad’s name, and means “daughter and joy.” It becomes exhausting when I’m asked to repeat my name over and over, and they still get it wrong.

I take exception to the second and third reactions. My name is not common, but claiming that it’s “unusual” is an example of othering. So, too, is abbreviating my name because it’s “too difficult.” I have been renamed “Nancy” or “Nadine,” and introduced to other people using this newly anointed moniker.

The fourth reaction concerns non-majority cultures and how these communities decide what constitutes a proper pronunciation. I say my name the way my parents do. But in talking to West Indians or South Asians, I’ve been told that I’m supposed to pronounce the letter “A” in my name like a “U.” Twitter users raised this very same issue about U.S. Vice President-elect Kamala Harris’ name, using terms like “white washed” and “bastardized” to describe the apparent Anglicization of her name as “Comma-la.”

Inevitably, I find myself caught between my apparent duty to adhere to ethnic tradition and the internalized pressure of assimilating into the majority culture. My sister got tired of correcting her friends and teachers, and decided to forgo both ethnic tradition and my parents’ pronunciation of her name. In high school, I would tell people to call me “Nan” to make it easier for them. As an adult, I want to be called by the name that reflects my personal and professional identity.

Othering by any other name

In the opening example, the client had made assumptions about my ethnic background. His deliberate effort to mispronounce and exaggerate my name was no mistake. Hyperforeignization occurs when a person misapplies foreign speech sounds — like saying Beijing with a “zh” sound or habanero with a “ñ” sound — to words they perceive as foreign.

Examples abound in U.S. politics. In an attempt to otherize vice president-elect Harris, Sen. David Perdue said “Kamala” three different ways to a crowd of supporters before dismissing her with a derisive “whatever.” President Donald Trump and Fox News hostTucker Carlson have feigned inability to say her name while also claiming that Harrisdoesn’t know how to say her own name. It’s clear that they don’t put the same effort into pronouncing Harris’ name as they do with uncommon names like Melania, Ivanka and Giuliani.

One explanation for the hyperforeignization of Harris’ name — and mine — is that it’s meant to signal to others that our names are foreign, un-North American, un-Western and unlike us. Researchers Rita Kohli and Daniel G. Solórzano have referred to these instances of mispronunciation as racial microaggressions, “subtle daily insults that, as a form of racism, support a racial and cultural hierarchy of minority inferiority.”

The impact of these purposeful mispronunciations, according to Dr. Kohli, is “deprofessionalization and othering.” This happened to me when a person in a position of power repeatedly addressed each of the white email recipients as “Dr.” and me as “Ms.”, even though I also have a PhD.

Regardless of intention, racial microaggressions, according to Dr. Kohli, reinforce the idea that we’re not from here and we’re not to be taken seriously. Microaggressions contribute topoor self-esteem and negative perceptions of one’s culture, as well as missed job opportunities,lower earnings and housing discrimination.

As with names, pronouns signify how we exist in the world and how people identify us. Misgendering is a regular occurrence for people who are transgender, nonbinary or gender nonconforming. Misgendering can be intentional or unintentional. I once had a client whose previous counselor had misgendered the perpetrator of their assault. Although the client felt the pronoun use wasn’t deliberate, they withdrew from counseling and didn’t return for over a year. This shows just how painful misgendering can be when it undermines confidence in health professionals.

Other clients described experiencing deadnaming. One client recalled how a professor refused to call them by their affirmed name, which was on the attendance list. Whether intentional or not, deadnaming can result in a person being outed before they are comfortable sharing their identity. The news coverage and social media response toElliot Page’s Twitter post about being transgender includedinstances of deadnaming, even when messages were intended to be supportive.

Imposing binary categories on people who expressly identify their pronouns is not only disrespectful, but also harmful. Transgender Canadians are more likely to experience violence, inappropriate behaviours publicly and online, poor mental health, suicidal ideation, and employment discrimination, compared to cisgender Canadians. Misgendering can be avoided by asking people what their pronouns are — in other words, treating them as the experts on their own identity.

People from the majority culture are quick to claim that instances of mispronunciation, misgendering and deadnaming are unintentional. Others, like author Jordan Peterson, use freedom of speechto justify their refusal to use gender-neutral pronouns. But it’s not up to the majority culture to decide whether something is intentional or offensive. Intention is immaterial when actions cause harm to a person’s life.

RELATED

- ‘Work Culture’ Is Code For White And Western. So Where Do People Like Me Fit?

- Tucker Carlson's Pronunciation Of 'Ottawa' Has People In Stitches

- Kobe, Kamala, And Other Popular Baby Names For 2020

Disrupting power dynamics means correcting mistakes and not letting wilful microagressions go unchecked. A refreshing example is comedian Hasan Minhaj, who appeared on The Ellen DeGeneres Show and insisted that the host pronounce his name correctly.

Names and pronouns are just a starting point. We can afford to stretch ourselves and learn about a person’s identity. What it comes down to is basic decency and respect.

Have a personal story you’d like to share on HuffPost Canada? You can find more information here on how to pitch and contact us.

You May Also Like

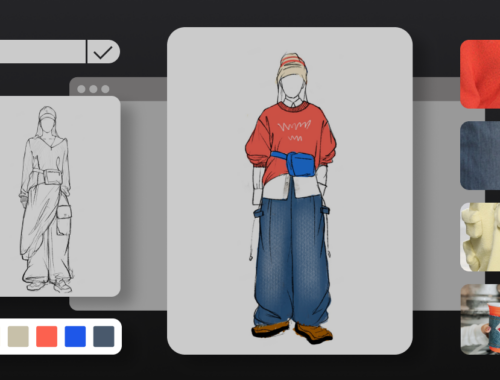

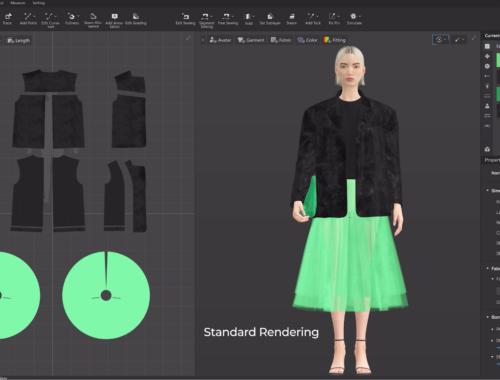

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

**AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability**

February 28, 2025