What the West Can Learn from Florida About Forest Fires

Fire has always been a part of the landscape. The mistake we made was trying to stop it—something Florida never did.

Joe O’Brien, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service, tucks his helmet into his chest, steals a breath of clean air, and steps closer to the fire now engulfing a $23,000 camera. Overhead, a drone that sounds like angry bees is darting in and out of the smoke column. A flock of nearby scientists are radioing to each other as they drag a boxy gadget on a pulley through dancing flames. O’Brien is one of several dozen scientists who traveled from around the country to a half-acre plot of longleaf pine forest north of Tallahassee, Florida, for the privilege of burning it all. He and all the scientists here are trying to answer the complex and poorly understood question of how fire burns. If they succeed, they hope to set more of America ablaze.

“All of the soil here is essentially beach sand,” O’Brien says, leaving his cameras to shoot infrared video of the fire. He tugs up a recently burned grass clump and shakes the sand from it with the sort of delighted disbelief you’d expect from a toddler discovering fountain drinks. “And yet there are as many 50 plant species per square meter here—richer than anywhere else on the planet!”

O’Brien, who studies rare plants and their relationship to fire in the Southeast, says the incredible plant diversity isn’t because of differences in the sand these plants grow in—it’s differences in the frequency, duration, and intensity that the forest burns. “Fire’s got this mojo about it,” O’Brien says. “It does a bunch of things that no other treatment, mechanical or chemical, can. It changes the chemistry. It volatizes compounds. It sterilizes the soil in some parts and adds nutrients to others.”

For years, fire scientists intuited this. But fire itself wasn’t fully quantifiable until the past couple decades, when Department of Defense scientists perfected infrared cameras that allowed them to shoot explosions at 1,000 images per second. When O’Brien trained those cameras on a forest fire, he found he could measure how temperature changed over time and space. With that information, he could determine how much energy the fire was putting back into the sand, even at the scale of a single clump of grass. Now, by mapping the energy distribution, O’Brien can predict which plants will spout where. Fire diversity creates biodiversity, and this longleaf pine forest is at its most biodiverse when it’s burned every year.

“When the flames go, the biodiversity follows,” O’Brien says, clearing his lungs with a cough. He says fire is an ecologic imperative—as important to the forest as water and sunlight. If these woods don’t burn for as little as two decades, they become too dense and wet to burn at all. Eighty-five percent of American forests are fire-adapted, but removing fire from most of those places produces a more familiar result: The forests grow thicker, and when the unavoidable fires return, they come as firestorms like those that are right now prompting the evacuations of thousands in northern California. O’Brien and all the scientists here think there is a universal “silver bullet” to America’s fire crisis: more fire.

You might call Kevin Heirs the Billy Graham of controlled burning. Heirs is a wildland fire scientist with Tall Timbers, the most evangelical prescribed-fire organization on the planet. He’s also the incident commander overseeing this research burn. “So it rained two inches two days ago, and we’re still gonna burn this afternoon,” Heirs told a room full of scientists wearing agency T-shirts tucked into green pants. It was the morning before the fire began. Tall and trim with a buzz cut, Heirs was standing at a dais at Tall Timbers Research Station. The fire-focused think tank sits on a former cotton plantation across a lake from Tallahassee. He wore a T-shirt that read “Wildland Fire Lighter!” On the wall beside him was a framed front page from the Tallahassee Times with the headline “It Seems Smokey the Bear Was Wrong!”

Though no work has been done to catalog all the land in the country that needs fire or thinning to restore it to its pre-European conditions, the Forest Service estimates that significantly more than half of the 193 million acres the agency manages is in a “disturbance deficit,” a calculation that also includes the average annual area either thinned with chainsaws or burned by wildfires over the past century. According to Nicole Valliant, a fire application specialist who wrote the report for the Forest Service, that number will only increase if nothing changes. And for much of that land, that means the risk of high intensity fires ratchets up. Heirs had invited around 90 different land managers and scientists from a dozen different state and federal agencies to this burn. He wanted them to approach prescribed fire-lighting with the same collaborative spirit that land management agencies take to firefighting. “Better science,” Heirs told the crowd, “will lead to more burning.”

The researchers had spent the past three days setting up more than $1 million in scientific equipment in the plot they’d burn that afternoon. In addition to O’Brien, one scientist had come from the University of Idaho to study pyro-aerial biology—microbes released by fires. Using a drone rigged with filters to capture particulates in the air, she was studying whether smoke can spread disease to people and crops. A scientist from the EPA was sharing that same drone to measure whether the smoke from megafires is unhealthier for people than smoke emitted from low-intensity burns like today’s. Another scientist from the Missoula Fire Lab was sampling gases released by the fire using “a seven-foot-long fishing pole.” Still another scientist from Florida State University had a crate-sized device developed by the wind turbine industry to measure wind speeds from 200 feet above the canopy to the forest floor. He wanted to measure fire’s feedback on the atmosphere.

Of these projects, the one Heirs found most promising for decreasing the risk of prescribed fire was by Rod Linn, a physicist from Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. Linn was funneling the results from these studies and more into a model that could predict how prescribed fires burn. Coarse models for forecasting a wildfire’s spread already exist, but none can predict a fire’s effect on the land: how placing more fire in one place might change the fire intensity in another; how heat released from the flames influences the atmosphere and how that feedback affects the fire; where the smoke will go, what’s in it, and how far it will travel. If he does his job, Linn can help land managers engineer their fires so they achieve exactly the results they'd hoped for. “If we can capture the physics correctly on small flames, the big flames get easier,” Linn says.

On the dais, Heirs, who calls prescribed burning an art and says that everywhere he goes, he imagines setting the woods ablaze, was twitching like he’d had three too many cups of coffee. For a certain type, setting the woods ablaze is joy. “Now let’s go see some fire!” he said.

For years, Florida’s fires were renegades. In the 1900s, Gifford Pinchot managed to squash American wildfires everywhere but in the Panhandle. For about 20 years, Floridians tried his ideas. Then hunters noticed that the quail they loved disappeared, so they flipped Pinchot and his suppression mandate the bird and brought torches back into the woods. The quail returned, and Floridians haven’t stopped since. Today, controlled fires are as cultural as NASCAR.

“The Thomas Fire burned 280,000 acres in Los Angeles and was front-page news for weeks,” Heirs tells me on the drive out to the research burn. That fire burned 1,000 homes. “In a 30-mile radius around Tallahassee, we burned the equivalent land, and it never made the news because we didn’t lose a single house.”

There are more fires in America than just disastrous ones. Last year, 202,250 prescribed fires burned approximately 12 million acres; 160,000 of those burns (8 million acres’ worth) were in the South. Ranchers, hunters, and homeowners all burn because it’s faster than raking and better for their pastures and woods. They usually skip the fire-resistant clothes and opt for blue jeans. At about 3,500 lightning strikes a day, Florida is our most electrical state, but fire and smoke are so common there that when a bolt does ignite a wildfire, it can burn for weeks and never cause a problem. “We really don’t have a good handle on how many acres burn in Florida each year. It’s a huge concern, because we want to know what hasn’t burned so we can know where to focus our efforts in the future,” Heirs says.

If it is a problem, it’s a palatable one because the fires are usually nonthreatening. Florida’s forests are damp and gridded with roads (“We never build hand line”). It’s flat (“Not many hills for them to run up”). Rain is forever on the near horizon (“We burn 365 days a year”). Even still, Heirs estimates Florida should be burning 1 million more acres each year than it does. He blames the state’s fire deficit, in part, on prioritizing suppression over ignition. When wildfires are burning, firefighters are shipped from every corner of the country to the front lines, leaving the forests that depend on prescribed fires without the workforce they need to light them. “We are creating problems where they didn’t exist by focusing exclusively out West,” Heirs says. Take, for example, the 2016 fires in southern Appalachia that destroyed 2,400 buildings and killed 14. Tennessee hadn’t seen that brand of fiery chaos in generations.

For many fire ecologists, “fire breeds fire” sums up their ideal exit from the fire trap. By letting wild flames burn, igniting more prescribed fires, and tying both of these into existing burn scars, land managers could knock bigger holes into monocultural forests. Controlling the fuel the fire burns checks the fire’s intensity.

As it is, the national strategy for thinning and burning prioritizes the 1.5 million homes and $50 billion in property built in areas designated as extreme fire risk. And very little gets done. Out West, fewer than 1 million acres see prescribed fire each year. The reason for this is partially that each national forest acts as a fiefdom, burning whatever acreage it can with whatever limited personnel are available before the fire season sucks them into triage. Heirs thinks we’re plugging a dam breach with Scotch tape. “Those are deployment sites,” he says, meaning a place where firefighters can survive a last stand beneath fire shelters. “How does a few hundred acres of treated forest protect a town from a fire that’s throwing embers two miles ahead of itself?!”

His is a risqué stance. (“That thinned forest is an anchor point, a place that gives firefighters a place to start protecting the communities and protect themselves,” says Valliant, the Forest Service’s fire application specialist. “Why wouldn’t you want that buffer?”) But Heirs believes the workload is too great and the workforce too small for all the towns and cities in the path of future megafires to simultaneously manage their way to safety. A better way, he says, is to triage extreme fire prevention just as we triage firefighting. Money and firefighters from around the country could come together and restore healthy fire to large chunks of one national forest at a time, then move on until the islands of fire-adapted woods once again become continents. And in the short term, brace for more of the same. “It took us 100 years to get into this problem. It’s gonna take that long to get out,” Heirs says.

We’re a long ways out. In the West, prescribed fires burn just 1 million acres a year. The woods are dense and often drought-stricken, which means to keep prescribe fires from becoming wild, burn plots first have to be thinned with chainsaws or tractors. Then there are budgets. In California’s Sierra Nevada alone, the backlog of land that needs either fire or thinning is about the size of Kentucky. Restoring that would cost between $6 billion and $8 billion. This year, the federal government made a record investment in fire mitigation, which includes prescribed burning. That was $430 million. Money and forest conditions are nuts-and-bolts challenges: knotty but solvable. “I’m not sure we could get it all done with a blank check,” says Jeremy Bailey, director of the Nature Conservancy’s fire program. The bigger problems are social. Westerners don’t like smoke and have good reason to fear fire.

After decades of industrial abuse on public lands, laws that protect clean water, clean air, and rare species intentionally slow management. Prescribed burns must meet National Environmental Policy Act muster. That can take years. Get through NEPA, and then air-quality boards have to sign off on smoke pollution that is unhealthy and unpleasant. Then a week must come when it’s dry but not too dry and windy enough to transport the smoke but not too windy to fan the flames. A 1,000-acre prescribed burn in Sequoia National Park took the incident commander a third of an almost 40-year career to find a window when all the various factors lined up. In the meantime, megafires, like those that for weeks inundated the Sacramento Valley with the worst air on the planet, turned 3.5 million acres of what was pine forests into brush fields. In many cases, the pines in California, like in New Mexico, aren’t likely to return.

“What we need is rapid conservation,” says Tim Male, director of the Policy Innovation Center, a nonprofit working to modernize environmental legislation. “We either act now or we lose species or forests permanently to climate change.” That will almost certainly require loosening the restrictions that slow prescribed fires, a difficult conversation. But if we do nothing, megafires will quickly lead us into whatever comes next.

Not surprisingly, Heirs thinks the model for the way forward is happening right here outside Tallahassee. “I mean, look at that,” he says, pointing out the window. A long strip of flames was several dozen feet from a home and near a major highway barely 15 miles from the capitol building of the country’s fourth most populous state. Nobody perceived a threat, and not a siren could be heard.

Back on the line with O’Brien comes the satisfying whoosh of gas catching fire. A few men and women in green and yellow fire-resistant clothes are pouring flames near O’Brien’s cameras to give him a bit more to work with. Pine needles near the ground begin to shake in the updrafts of rising heat, and the tiny lights on instruments blink out their confirmation that science is happening.

“There’s a legacy in the country of environmental nihilism, that everything humans do to the land is bad,” O’Brien says, stepping across the three-foot-wide swatch mowed into the forest to keep the research burn in its half-acre box. He spins off a story about the recent discovery of a 14,500-year-old mastodon tusk, the marrow “scooped mechanically” as he put it, in a nearby limestone stream. The evidence of human-lit fires in the geologic record appears around the same time, which strongly suggests to O'Brien that the plants in these forests evolved to fires lit by people to cultivate food, make travel through the woods easier, or, as native Hondurans who still use fire today told O’Brien, “because it looks better.” Historically, America’s lands were structured by human ignitions.

That’s as true today as it's ever been. In the Flint Hills of Kansas, ranchers burn more than 2 million acres a year to restore grasslands. If a ranch owner doesn’t want their lands burned, it’s their responsibility to keep the flames away, not the burners’. In Orleans, a tiny town in Northern California, the population of mostly Karuk Indians proactively burn around their homes so the Forest Service doesn’t have to fight the fires that come to their backyards every summer. Naturally or unnaturally, one new study found that people, by starting wildfires with our cigarettes, campfires, and dangling trailer chains, have tripled the length of the modern fire season. O’Brien shrugs at this, then bristles at the fact that we fight to the death any fire not lit by lightning. He says we shouldn’t judge a fire by how it started but by what it does for the land. “At what point did we become unnatural?” O’Brien asks. “We should be asking the same question people have always asked, which is what do we want the land to look like?”

Smoke from the tiny fire lifts and disperses, and the drone buzzes off to somewhere else, leaving O’Brien amid the pop and crackle of grass that burned this year and will burn again next year. O’Brien knows burning and thinning challenges modern environmentalism: Man isn’t nature, and nature can handle itself. He’s OK with that. As a conservationist, O'Brien doesn’t like the alternative.

“Whether we plan the direction it goes in a thoughtful and sophisticated and reasonable way or just let it happen, nature marches on,” O’Brien says. “But I’ve got a little girl now. I hope we go the planned way instead of letting the chips fall as they may.”

You May Also Like

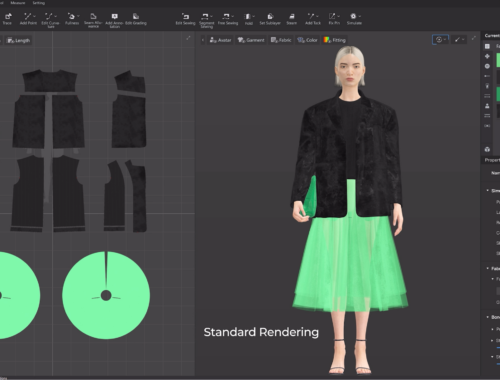

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

February 28, 2025

Block Blast: The Ultimate Puzzle Challenge

March 19, 2025