What the New York Times Got Wrong About Female Runners

The recent story about Katelyn Tuohy perpetuates a dangerous narrative: that normal physical development is a hurdle to overcome

On Friday, The New York Times published an article on its website about star high school runner Katelyn Tuohy, with the headline “America’s Next Great Running Hope, and One of the Cruelest Twists in Youth Sports.” (The print edition of the article, which appeared the next day, had a slightly more subdued title: “Toughest Part Is Ahead for a Distance Running Phenom.”) The piece, written by frequent Times sports contributor Matthew Futterman, began by highlighting some of Tuohy’s accomplishments: although she is only a sophomore, Tuohy has already set national records in the 3,200 and 5,000-meters. The article quickly changes tack, however, in order to make the point that many top female high school runners fail to live up to their early promise because of changes to their physique. One of the “cruelest twists in youth sports,” it seems, is that girls become women.

Not everyone was enamored with this thesis.

Two-time 5,000-meter national champion Lauren Fleshman spoke for many when she tweeted:

In another tweet, Fleshman added that we should abstain from gushing about “child prodigies” until these young runners are actually vying for medals on the world stage.

Others criticized the author’s decision to cite Mary Cain, another high school standout from New York, as an example of a former teenage star whose career has “largely stalled.” Cain, as more than one person noted, has only just turned 22 and hence still has several years to develop and improve. Cain’s fellow ex-Oregon Project member Mo Farah, to give just one example, was a fairly “average” professional until breaking out in his mid-to-late 20s. Farah is now arguably considered the best track runner of all time and his example should suggest that sometimes it takes time for talent to develop, for men as well as women.

Which isn’t to suggest that the development process is going to be the same for both sexes.

As Kara Goucher put it to me: “The typical female experience is a bumpy one. But talent never goes away. Once these women/girls adjust to a mature body the talent can come through again. The obsession with labeling these girls the ‘next big thing’ is part of the problem . . . Katelyn is very talented. She will grow, and possibly slow. But once she adjusts, if she still has the love, her talent will still be there.”

In fairness, one thing that stands out when reading Futterman’s article, in light of the backlash it received, is that he makes an attempt to voice the very same concerns as his critics. This is particularly apparent in a section on Melody Fairchild, who in the early ’90s was called the “greatest high school runner ever,” and whose career subsequently went “off course.”

“Looking back on those years, Fairchild said she, like so many other young, talented runners, failed to understand that the ups and downs she experienced as her body evolved were normal,” Futterman writes. “Nature was doing what it is supposed to do for young girls as they become women—add fat and prepare the body for reproduction. That otherwise healthy development, however, does not help an elite runner maintain her speed.”

Elsewhere, Futterman cites Fairchild saying that it is a “dangerous” to send the message to young women that they should “fight to regain their high school physiques.” She goes on: “We want them to embrace being in a strong woman’s body.”

The obvious irony here is that whole premise of Futterman’s piece is to highlight the idea that the healthy development of young women’s bodies can, at least temporarily, impede their athletic progress. This may not be the same thing as encouraging young women to regain their high school physiques, but it does emphasize the notion that these physiques might be advantageous when it comes to competitive distance running. Without putting this claim into further perspective by, say, stressing that women’s track and field world records are held by (brace yourself) women—as opposed to girls—the article seems to inadvertently push the same “dangerous” message that it decries.

It’s similarly ill-advised to describe any performance decline that may be the result of the normal maturing of young women’s bodies as a “cruel puzzle,” as Futterman does at one point in the article.

It’s not a cruel puzzle. Certainly not any more than any of the other ostensibly unpredictable developments that beset elite runners. As a number of commentators have already noted on Twitter, no running career is a linear progression towards success. Why did Mo Farah suddenly start to blossom in his late 20s? Why did Ryan Hall suffer such a precipitous decline at an age when most marathoners peak? How did Jordan Hasay, who won the national high school cross-country championships as a freshman(!), somehow manage to avoid the bane of womanhood to become the second fastest U.S. marathoner ever as a 26-year-old?

As for Tuohy and her fellow high school runners, I think Fleshman and Goucher are right in that we should forswear speculating about their future potential. (I’ll be the first to admit that this is easier said than done.) Unless these young talents are already throwing down world-class times—like 17-year-old Norwegian world-beater Jakob Ingebrigtsen—their accomplishments should be celebrated within the context of their current athletic level. Who knows? Maybe Katelyn Tuohy will eventually decide that she doesn’t have any interest in becoming a professional or collegiate runner. For now, she can savor being a 16-year-old who holds two high school national records. There’s nothing cruel about that.

You May Also Like

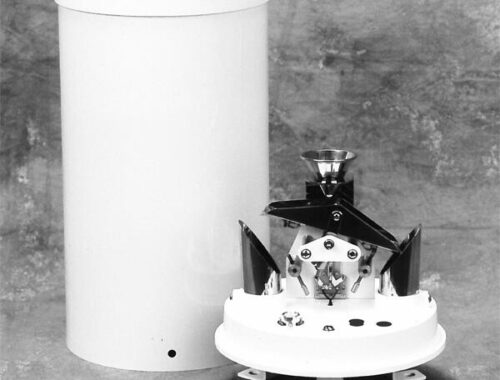

Automatic Weather Station: Real-Time Environmental Monitoring and Data Collection

March 14, 2025

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025