What Shark Experts Really Think About Shark Week

>

Discovery Channel’s Shark Week kicked off July 22 for the 30th summer in a row. While millions of Americans are reliably entertained by the documentaries and celebrity specials, marine biologists will often spend the week on social media, freaking out about distortions and myths put forth by Shark Week programming. Perhaps the best example of this came from shark conservation biologist David Shiffman in 2014, as he live-tweeted his reactions to every single Shark Week show that year—“pseudoscience,” he wrote; “dangerous and disrespectful.” “Watch as Shark Week slowly drives this shark scientist insane,” Vox summarized.

Discovery has made conscious efforts to improve its Shark Week content since then. We called up Shiffman—who is a scientist at Simon Fraser University and writer for a blog called Southern Fried Science—and several other scientists to talk about what to expect from this year’s programming, and whether Shark Week is good or bad for sharks.

Also on the line: Jim Wharton, the director of conservation and education at the Seattle Aquarium; Vicky Vásquez, a graduate student with the Pacific Shark Research Center at Moss Landing Marine Labs; and Lucy Howey, a marine biologist specializing in oceanic whitetip sharks, who also works for Microwave Telemetry, Inc., which makes satellite tracking tags for birds and sharks.

JIM WHARTON: I was approached by Shark Week a few years ago, after years of advocating for Alien Sharks online. Alien Sharks [a program about deep-sea shark species], in my opinion, is one of the best programs Shark Week has ever produced. It’s one of the very few that emphasizes other sharks rather than great whites and bull sharks and tiger sharks.

In 2015 I did commentary for Ninja Sharks [about species that have evolved to become very effective hunters]. It was a mixed bag of an experience because the content of Ninja Sharks sounded really good, but the title was atrocious. From the beginning I was trying to get them to alter the title and a little bit of the approach. I managed to have some impact—they sent me an early edit of the show, and there was some very unfortunate fear-based messaging, and to their credit they were willing to soften and change it a little bit.

LUCY HOWEY: I’ve done maybe three shows with them at this point. I have mixed feelings about it. It’s nice to get our work out there. One of the big things is just getting the public interested in sharks, and I think Shark Week is great for doing that. But I tried to get them to change the title, Monster Tag. I told them, “You’re cheapening this show by calling it this.” And they kept the name. I must have given them 50 other names. We fought them on the content and didn't get anywhere. At the very beginning, we wouldn’t sign the papers to film with them because the non-disclosure agreement was ridiculous. There was a line in it that said something like they could present us however they wanted, even if it wasn’t accurate, or even if it was slanderous. I was like, “This is my career. I’m not going to sign something that says you can defame me.” They changed the agreement, in their defense.

(A representative from Discovery responded, “Participants sign agreements sometimes with us and sometimes with producers. We don’t comment on legal agreements.”)

DAVID SHIFFMAN: I have not, and likely will never be, on an actual Shark Week program. But I’ve had lots of productive conversations with people behind the scenes that have started off with “Hey, you’re so critical about this. What would you like to see?” So to their credit, they approached me with that, and I gave them a long list of things, and they have followed up on several of them. There has been a real shift in programming in the last few years. It was really bad in the days of Megalodon, Wrath of Submarine, and all of that nonsense. The Alien Sharks and Ninja Sharks programs have been some of my favorites. I’ve been very critical of programming overall but those are the really interesting ones, focusing on species that don't get enough attention, with an emphasis on real behaviors.

VICKY VÁSQUEZ: Moss Landing has been featured on Alien Sharks, just about every one of those shows I believe, and I got a chance to be on Alien Sharks: Stranger Fins last year. I feel really lucky to be a part of the show that I was on. I know that a lot of people have had bad experiences with Shark Week and it’s left a bad taste in their mouth but for me, it’s just been so positive, so special. I did not expect myself to become a Shark Week cheerleader over time.

VÁSQUEZ: After going to the Sharks International Conference in Durban, South Africa, four years ago, there was just this clear representation of diversity. It was amazing seeing so many women scientists, so many people of color. One thing that had bothered me about Shark Week was, when you look at the Shark Week shows, you're not necessarily seeing that representation. So for Southern Fried Science, I wrote a piece saying how it would be nice if they looked for this, because it's not necessarily about trying to meet a diversity quota—it's about the fact that diversity is already there. You can basically trip on it. I think that's rare in a lot of fields in science. The producer of Alien Sharks: Stranger Fins told me when we were out in the field that he actually had read that article and it was one of the reasons why he wanted to include me.

SHIFFMAN: This year, Shark Week did something that annoyed me a great deal. On their official press release listing all the shows, any time there's a male scientist in the show, it lists them by name in the promo. But any time there's a female scientist, it lists "a team of scientists"and not their name. And in some cases there was a male scientist listed as “Dr. so and so” and a woman scientist where it listed their name without “Dr.”

(A representative from Discovery responded, “Because of the sheer amount of scientists on our air during Shark Week, we rely heavily on the information we get from the production companies.”)

HOWEY: This is just speculation, but [with Monster Tag], I really felt that. My collaborator, Ed, did nothing to get the attention on him but they were really focusing on him. He was like, “I don’t know the answer to this, ask Lucy.” I thought maybe I was imagining it.

SHIFFMAN: No, you’re not. It’s an issue. And they are absolutely trying to improve. But either one year or two years after Vicky wrote that great blog post, they had a series of little three-to-five minute webisodes focused on women scientists and scientists of color, but they were on the website, which no one looks at—not on the most widely viewed cable news science and environment show in the world. It's nice to see that they're trying, but the American Elasmobranch Society (a non-profit professional organization for shark scientists) is more than half women, and you see Shark Week lineups are almost all men. If you’re looking for shark researchers and finding all men, at a certain point it’s not accidental.

(A representative from Discovery responded, “We have made a concerted effort to have more woman scientists on our air and our numbers are up (getting a count). And we are working on continuing in that direction. We are working to make sure that more female scientists represented, and this year we had 12 female scientists on shows. The goal is to keep growing that number.”)

HOWEY: On Monster Tag, they had celebrities paired with scientists. They had me with Lindsey Vonn, who loves sharks, and is super brave. They were trying to get her to act more scared, and she was just like, “Whatever. I fly down a mountain at 120 miles per hour.” She wasn't biting. I have seen the show and I will say they definitely sensationalized a lot of it.

SHIFFMAN: It’s not just limited to Shark Week, but Shark Week absolutely perpetuates the idea that this is an old boys’ club, and there's macho nonsense associated with it. We worked with a bunch of film crews [not related to Shark Week] during my Ph.D. experience. On one occasion, I was the senior scientist onboard and I was reeling in a large shark and it was too heavy for me. So I handed it to a graduate student on our team who is a young woman, about five foot three, and is a member of a sorority, perhaps not a stereotypical field researcher, but is one of the hardest-working and strongest people I’ve ever met. A producer for this show pulled me aside and said, “Why did you let that little girl reel in the shark instead of you?” And I said, “Because she's a lot stronger than me.”

SHIFFMAN: A few years ago they aired, I believe, seven different episodes featuring a team of non-scientist shark enthusiasts. They’d have a basic question about shark behavior that scientists had answered 30 or 40 years ago. They didn't ask any scientists, they assumed no one had ever answered it, and their solution was, “Let's go cage diving with great white sharks in Mexico and see if we can observe this behavior.”

WHARTON: I don't know if it's the 30th anniversary thing, but they really have gone all in on the celebrity guests this year. It's a little nuts—it’s almost like they've run out of interesting things to say about sharks and so they’re distracting us with celebrities. You'd think in an entire week of programming, you could go with enough of the stuff that works but still have plenty of room to take risks. I feel like Alien Sharks was one of those risks that obviously paid off.

Why not try to broaden your experience instead of just falling back on the same thing for every single show? There are always about two or three shows at minimum that are just straight attack porn. They’re either recreating attacks, or they're talking about shark attacks being on the rise or being an epidemic. It’s unfortunate, because it’s the least important topic to discuss with sharks.

HOWEY: I think they feel trapped by what they perceive to be what will sell. If a program does well and a personality is well received, then they want to bring that individual back over and over again. It’s funny to think that a network that’s producing a week about sharks is risk-averse, but that definitely seems like that is one of their criteria. They just want to do things that they know are going to work. We filmed an amazing story for the show about pregnant oceanic whitetip sharks. We were doing ultrasounds in the field on them, and then tracking them. But they were very concerned about getting the sensational shots. You know, “We want to see Lindsey in the water with a shark.” And I worked with her on what to say about the sharks, and I think she did a really great job. I think that they cut out a lot of footage that shows the real science that happened. That’s disappointing, but it could be worse.

(A representative from Discovery said, “We are an entertainment network and our goal is to expose as many people as possible to the importance of shark conservation, on our air, online and in all of our outreach. It’s science first, but mixed with entertainment to keep the audiences engaged. Discovery gives sharks and the men and women who work to protect them a platform to highlight the importance of conserving these beautiful and greatly needed creatures of our ocean’s ecosystem.”)

WHARTON: It’s funny that the titles sometimes are not indicative of the content. For example, with Alien Sharks and Ninja Sharks, the titles keep a lot of people away. Shark advocates, people who are interested in conservation—I get a lot of feedback from Twitter from people who have written Shark Week off, and used the titles as a reason not to come back.

SHIFFMAN: Back when I was much more against what Shark Week was doing, before they made serious efforts to improve, I cultivated some sources within Discovery, and one told me the story of how they come up with the titles. I’ve been unable to confirm, but this is perhaps worth looking into: The producers have no input at all into their show titles.

HOWEY: That’s true. I can confirm that for sure.

SHIFFMAN: They can propose a title, but then the Discovery marketing team and science education team sits around and watches all of them in a boardroom, allegedly while drinking. And comes up with the titles. Later in the viewing party, the titles get progressively more ridiculous.

VÁSQUEZ: A little thought on the names of the titles might help people get a better picture. I think that helps people go and want to watch that show because they know what they're going to get.

(A representative from Discovery responded, “Production companies are consulted but ultimately it’s up to the network on what the show names will be.”)

VÁSQUEZ: The audience needs to remember their power. Shark Week is constantly looking for feedback, and what they do with it is unfortunately out of our hands, but the one thing that we can do is encourage audiences to watch the shows that we know are going in the right direction. I’m the deputy director of a group called the Ocean Research Foundation, and in the past we've put out little Shark Week schedules [with commentary] tipping the audience: “We think this show is going to have strong science content, we think this show might be more fear-based,” and so on. I think there are a lot of people out there who are hungry for the right stuff, in terms of content and diversity.

SHIFFMAN: I try to come up with an annual list of what to watch and what not to watch. What I've been suggesting is that people watch the good shows and enthusiastically share on social media, tagging Discovery and Discovery's execs, to let them know that they're watching.

VÁSQUEZ: I do know that the execs are looking at a lot of this in real time. If audiences want their voices to be heard, the best thing would be to say something while that show is premiering. That's what they're really looking for. If you write your opinion two weeks later, when you're watching a rerun, it’s still helpful, in my opinion, but the people that make decisions may not notice it.

HOWEY: A couple years ago I read that one of the most Googled questions of all time was “What would it be like if dinosaurs were still around?” We don’t want to get to the point where we’re saying, “What would it be like if sharks were still around?” If there is anything good that can come out of Shark Week, people protect what they love, and they love what they know. So, whether you love it because you like to watch the horror, or the conservation tree-hugger kind of shows—either way, they’re getting exposure for sharks. Again, I really disagree with some of things that they’ve done and how they’ve portrayed sharks, but I think just getting exposure is a powerful tool.

WHARTON: I know dozens of marine scientists and advocates who grew up on Shark Week and were inspired by it. In the same way that Jaws is often decried as the worst thing that ever happened to sharks, it also inspired a lot of shark enthusiasts. I have VHS tapes of some of the first years of Shark Week because I used to watch them over and over again. For all of the frustration that we might feel for the way they present sharks, there’s still a clear signal of that enthusiasm that people embrace during Shark Week. This is the one time of year when we’re all talking about sharks. So to totally write it off and just pretend that it’s not this great opportunity is foolish.

VÁSQUEZ: Yeah. I grew up watching Shark Week too, and I used to take notes.

SHIFFMAN: Shark Week represents the largest temporary increase in how much Americans pay attention to any science or nature or environment topic at all, of the whole year, and has for decades. Scientists and environmentalists can use this temporary increase in public attention to get real information out there, regardless of the content of the actual shows. It would be great if the actual shows had better content.

You May Also Like

Essential Pool Supplies for a Perfect Swimming Experience

March 18, 2025

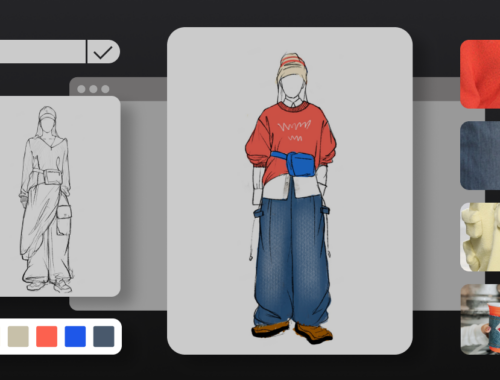

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025