What I Learned from a Month on the Carnivore Diet

This fall I joined the ranks of Shawn Baker’s all-meat cult for 30 days. Here’s what happened.

“Only 30 days,” I whispered to myself. “It’s only 30 days.”

This spontaneous pep talk happened at my parents’ house on September 1, opening day of my monthlong plan to turn nutritional orthodoxy on its head. For the third time in barely an hour, I rushed with the urgency of an Olympic race walker to the closest bathroom. Let me be emphatic: I was not urinating.

That morning I had embarked on a dietary mission to eat only meat for 30 days. Later that afternoon, after my wife and I arrived at my parents’ place for a visit, my first meal hit me. I braced myself on the toilet in a state of disbelief—first, at what a single steak breakfast was doing to my body, and second, at my mother for failing to discover the virtues of two-ply toilet paper.

I initially heard about the carnivore diet in late 2017, when Shawn Baker was a guest on Joe Rogan’s popular podcast. For two years, the 52-year-old weight lifter and trained orthopedic surgeon has eaten an average of four pounds of meat every day. No fruits, vegetables, bread, or sugar, although eggs and fish were fair game. “If you would’ve asked me two years ago, I would’ve said, ‘That’s fucking crazy,’” Baker told Rogan while explaining his daily menu. “I did it for a month and thought, Man, I feel pretty good.”

Since then, a cult-like following has branded Baker the unofficial Carnivore King. Men and women of all ages get in touch to share their dietary transformations: there’s a formerly vegan mother of three whose before and after photos Baker reposted, and a bespectacled amateur bodybuilder who dropped 210 pounds after jumping on the carnivore bandwagon. For his nearly 60,000 Instagram followers, Baker routinely posts success stories of folks who embraced animal protein and found nutritional nirvana. “I’ve been 98% carnivore since May 2018. I’m now down 42lbs,” one woman posted in early November. “My inflammation is pretty much gone. My brain is back. My energy is returning. I just bought my first size 6 jeans since I was 20 years old. I haven’t worked out one time.”

While Baker is generally viewed as the all-meat diet’s chief evangelist, a robust online community of fellow carnivores has emerged. There are more than 25,000 members of the World Carnivore Tribe group on Facebook. About 125 novice and longtime dieters have shared their stories at MeatHeals.com, a website Baker publishes. And a simple search for #MeatHeals on Instagram yields some 50,000 posts. Two other high-profile devotees of the lifestyle are Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson and his daughter, Mikhaila Peterson, who credits carnivory for sending her severe arthritis, depression, fatigue, and itchy skin into remission. Baker and his followers also claim the diet improves sleep, eliminates joint pain, increases energy, decreases weight, and pumps up libido. “I have no intention of saying I’m never going to eat anything else for the rest of my life,” Baker told me in September. “But as long as I’m feeling good and performing well, I don’t want to eat anything else.”

It all sounded wonderful. But would it work for me? I had to find out. Listening to Baker, I couldn’t help thinking about my own poor eating habits, which are at least partially a result of the frenetic nature of my job as a freelancer. Among my staples: pizza, burritos, burgers, and coffee—sometimes as many as five cups a day. I’m fortunate to have been blessed by genetics: I’m a 125-pound ectomorph with a fast metabolism, but as I inched closer to 30, I noticed that I had less energy.

Health professionals have many concerns about the diet—both for what it omits (vitamins, fiber) and for the rising risk of longterm diseases that can result from excessive red-meat consumption. There’s also the fact that the claims made by Baker and his followers are mainly anecdotal.

Still, I wanted a change, so I purchased 40 pounds of steak. Not being a seasoned carnivore, I simply loaded up my cart with what I thought would sustain me for a month. With $170 worth of meat in hand, I kicked off my 30-day journey with a steak and eggs breakfast. I felt fine: full but not bloated, sated but not groggy. And then came the diarrhea.

Baker discovered the carnivore diet in 2016, not long after he began noticing the effects of middle age. He had always been a big weight lifter, breaking records by deadlifting 772 pounds and winning contests predicated on feats of strength, including the 2010 Highland Games in Colorado, where he chucked a pitchfork hooked to a 16-pound bag of straw 34 feet into the air. A brawny man with a thick neck and a square jaw, and usually tank-topped, he looks abundantly healthy.

By age 45, Baker found himself maxed out at the gym. Despite being a medical professional—he completed his residency in orthopedic surgery at the University of Texas in 2006—he didn’t know how to curb his high blood pressure or manage his weight. So he began experimenting with diet. First he went paleo, consuming only meat and produce, and followed that up with a stint on a low-carb diet. Then he tested out a high-fat ketogenic diet. By that point he had lost 50 pounds but still felt sluggish. After reading about various diets online, he discovered Vince Gironda, a bodybuilding great from the 1950s and 1960s who advocated a curious approach: steak and eggs with a minimal amount of carbs mixed in. Baker was hooked, and Gironda’s diet became his gateway into full-blown carnivorism.

“I felt best when I was just doing steak and eggs,” Baker said during a video chat in September. When I reached him by Skype, he was animated and engaging, and very open to talking about how much carnivory had changed his life. “Then I kind of stumbled across these people that had been doing a carnivore diet for a long time,” he said. That included Joe and Charlene Andersen, a married couple seemingly lifted from the pages of a fitness magazine, who claimed to have lived on a diet of rib eye steak and spring water for nearly 20 years. (They declined to comment for this story.)

In 2016, Baker tried the carnivore diet for a week, then two weeks, then a month. Out of curiosity, he went back to his ketogenic diet, which included greens and dairy, but he didn’t feel as good. “It was like, I don’t really enjoy all this salad anyway. That was essentially the difference. It didn’t taste that good to me,” he said. Beginning in 2017, he returned to the all-meat diet for good.

Baker’s enthusiasm for the diet soon spread beyond his own life. While working as an orthopedic surgeon in New Mexico, he began discussing diet with patients suffering from osteoarthritis and other conditions. “I was basically practicing lifestyle medicine instead of strictly performing surgery,” he told me. A dispute with the hospital ensued, and in 2017, Baker was forced to surrender his medical license pending an independent evaluation, which occurred at the end of 2017. “The evaluation said there’s nothing wrong with me. I’m completely competent to practice medicine,” he said. He now lives in California and expects to have his medical license reinstated in February.

It was during this time that Baker became known as the Carnivore King, something, he said, that happened gradually after he joined Instagram in early 2017. “It’s been organic and spontaneous. I just started telling my story, and people got interested in it,” he said. Baker has supported himself financially by offering online diet consultations at $190 a pop, selling T-shirts, and doing the occasional public-speaking gig. (He’s also tried his hand at writing: his cookbook, The Carnivore Diet, will be published in April.)

While Baker is a happy convert, he’s not a zealot. He doesn’t push an all-meat diet on his three kids, for instance; he allows them to eat fruit and dairy but very little processed sugar. When I spoke to Baker in September, he had been on a carnivore diet for more than 18 consecutive months. He enjoys fatty cuts of steak like rib eye but incorporates eggs, bacon, chicken, salmon, and shrimp. Every so often, he’ll throw in a piece of cheese. Most of his diet is beef, but if it’s meat, he’ll eat it. Normally, people consume about 100 grams of protein per day. On a diet like Baker’s, that number skyrockets to nearly 500 grams, flouting the sorts of food guidelines groups like the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommend.

“There’s a lot of people that earn a living by making nutrition complicated,” Baker told me. “When I say, ‘Just eat a damn steak and you’ll be fine,’ that offends a lot of people.”

Eating a damn steak sounded simple enough. But prior to beginning my all-meat-all-the-time grubfest, I asked Baker if he had any advice.

His instructions were basic: don’t worry about weight, and eat whenever you’re hungry. “Kick those carb and sugar cravings,” he said. “It’s about changing your relationship with food.” No vegetables, no fruits, no bread, no sweeteners, no milk—and no beer. I drank whiskey and red wine, but only in small quantities, as Baker prescribed. The general rule, given my weight, was to eat about two pounds of meat a day. I ate mostly steak, but also chicken, salmon, and brisket. My wife, a veteran CrossFit participant, isn’t a big fan of steak, but she does like salmon, brisket, and chicken, so I’d cook up several steaks along with some chicken or fish. (Fortunately for us, our house has two bathrooms.) For snacks I ate venison and chicken protein bars. According to Baker, red meat tends to be favored by carnivore dieters: after all, a fatty rib eye is more flavorful than bland chicken.

Every day, I checked my weight, my blood pressure, and my fasting-glucose level—the amount of blood sugar in my body—with a glucometer. I also weighed the meat I ate and tallied the glasses of water and the cups of coffee I drank. (If you’re interested in the TL;DR version, check out this spreadsheet of my September diet. Yes, it includes a column for bowel movements.)

Like a lot of diets, the most difficult part is sticking with it when you aren’t near your own kitchen. Away on a reporting trip early in the month, I found myself sitting in a roadside motel room, using a plastic fork to pick the protein out of a ten-inch steak sandwich. Initially, the desire to cheat was strong. A diet of meat and eggs gets boring pretty quickly.

But after a week I was pretty well acclimated and enjoying a satisfying mix of chuck, strip, and rib eye steak. My guts were playing nice, too; no more power-walking to the toilet. I noticed that I was sleeping better, and I felt less sluggish each morning and more energetic in the afternoon, which is normally when I’d be pouring my third or fourth cup of coffee. For most of the month, I drank only two cups a day without deliberately trying to cut back. And while I lost several pounds—a result of the water content in my body shifting as I got used to a diet without carbohydrates—I never felt famished. In the gym, I was soon benching 130 pounds with ease. (Hey, it’s a lot for me.) My cravings for other foods subsided. Blowing up my diet forced me to focus on how my meals were prepared, how much I ate, and whether I felt nourished or bloated afterward. For the very first time, I cared about what I put in my body. I really did feel good.

And then came a fresh onslaught of diarrhea.

Frankly, it surprised me. I’d read articles before starting the diet that noted constipation as the main problem of carnivorous living. That seemed to make sense: you’re not getting any fiber. But when I started searching for answers, and a possible treatment, I turned up numerous carnivores who mentioned diarrhea. In an interview she did on Rogan’s podcast in August, Mikhaila Peterson said that her bloating and diarrhea persisted for weeks before it sorted itself out.

The reason has to do with how the body absorbs and digests fat, according to Teresa Fung, a professor of nutrition at Boston’s Simmons University. Glucose is the body’s preferred fuel, but in the absence of glucose-rich carbs, it turns to the fattiness of meat for energy. Usually, once fat hits the small intestine, signal molecules tell the pancreas to secrete lipase, a fat-digesting enzyme. The body normally produces enough of the enzyme to process the fat. Not so on a carnivore diet, at least at first. The amount of fat I was eating had surpassed my body’s ability to break it down. My colon had become a biodome of water and undigested fat. It got so bad that eventually I had to take lipase supplements—two capsules before every meal. That, along with some Imodium, improved matters. (“If you keep this up, I would be very worried about you,” Fung told me during our interview, which took place at the end of my 30-day test.)

“The diarrhea thing is very common,” said Baker, who also recommended that I stick with the diet for 60 to 90 days.

Later on I encountered another snag. During the final week of September, I noticed consistently rising fasting-glucose readings: 95, 106, 96, 100, 102. Fasting-blood-sugar readings above 100 indicate prediabetes; score 126 or higher on two separate tests and you have diabetes. (In May, some online critics singled out Baker after he publicly shared bloodwork revealing that his fasting-glucose level was 127.)

To help me distill this information, I turned to Stanford University School of Medicine professor (and vegetarian) Christopher Gardner. He said that while the human body can store a few pounds of carbohydrates and boasts an endless capacity for holding on to fat, it doesn’t store protein. Over the course of the day, protein helps make and repair cells, produce enzymes, and complete various other tasks. By the end of the month, I was regularly eating hundreds of grams of protein per day, way more than I needed. As a result, my body was trying to convert that excess protein into energy.

“As soon as you’ve met your capacity for other things, amino acids from protein will turn into glucose,” Gardner said. “That’s probably why your blood glucose is going up.”

While Baker allows that not everyone should be a strict carnivore, he does wear the mantle of Carnivore King proudly, using Instagram to poke at the vegans and vegetarians who fault his relationship with food.

“My goal is not to necessarily denigrate anyone,” he told me. “It’s to expose as many people to this diet as possible, because it’s potentially helpful.”

Unsurprisingly, it’s not hard to find doctors and nutritionists who object. “We have no evidence that this is a good idea,” John Ioannidis, a clinical epidemiologist and professor of health research and policy at the Stanford School of Medicine, told me. “We have mostly indirect evidence that this is a bad idea.”

Animal protein tends to throw the balance of good and bad cholesterol in our bodies out of whack, which can lead to cardiovascular disease. According to the World Health Organization, red meat is associated with higher long-term risk of diabetes and colorectal cancer. Questions remain about the carnivore diet’s effect on the gut microbiome (the healthy bacteria that live in the colon, aid in immune response, and subsist on fiber). There’s also an insidious, unseen risk that comes with heavy meat consumption: meat is highly anabolic, which stimulates cell growth and boosts metabolism. Repeated studies show that such stimulation can make us age faster.

The lack of dietary fiber is of particular concern to personal trainer (and known self-experimenter) Ben Greenfield, who points out that the prebiotics and probiotics necessary to feed the gut microbiome—which plays a role in the long-term health of the immune system—aren’t present in significant quantities in meat like they are in vegetables. Last May, he offered a critical assessment of the carnivore diet on Rogan’s podcast.

“This points to a bigger cultural issue,” Greenfield told me over the phone. “So many people have distanced themselves from a healthy relationship with food that all of a sudden they’re saying, ‘Fuck it, I’m just going to eat one food group.’”

Opponents of the diet also bring up the environmental hubris of focusing on a food group that contributes to 14.5 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions, according to the United Nations. The figure cited by the UN is a so-called life-cycle assessment number, which takes into account the feed, fertilizer, and land required to raise not just cattle but other meat-yielding livestock such as pigs and chickens. In the U.S., beef contributes only 2 percent of overall greenhouse-gas emissions, according to Sara Place, senior director of sustainable beef production research for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. But research from 2017 argues that substituting beans for beef could provide three quarters of the emissions reductions needed for the U.S. reach its 2020 goals.

But perhaps the biggest question mark is why exactly some people’s bodies seem to respond so well to the carnivore diet. “It’s really hard to tease out whether it’s the presence of meat or the absence of other things,” said Gardner, noting that eliminating sugar, junk food, and wheat products—especially white-flour products like pizza, bagels, and cereals—makes us healthier.

Baker parries these concerns. When I brought up his higher fasting glucose, he pointed out that he’s not diabetic, citing a study that suggested high-performance athletes who wore continuous glucose monitors routinely registered very high blood sugar levels. And a recent coronary-artery calcium scan, one of the best predictors of cardiovascular risk, showed zero calcification of his arteries, he noted. As for the World Health Organization, Baker pointed to its own literature, which allows that estimating cancer risk associated with red-meat consumption is difficult to do because the evidence that red meat causes cancer isn’t as clear-cut as the evidence that processed meat (your fast-food cheeseburger) does.

“I think it’s fine to be skeptical,” Baker explained. “I would have been skeptical, too. But if you’re overweight, you’re tired, you have no libido, your joints hurt, you’re depressed, and you go on a diet and all of that gets better, the question is: Are you healthier?”

On the final Saturday of September, I ate four eggs for breakfast and a bunless bacon burger for lunch, then showed up at my brother-in-law’s house with a can of sea salt and ten pounds of meat: four thick strip steaks and four fatty rib eyes. I immediately called dibs on a strip and a rib eye, two juicy pounds we cooked to medium rare on the grill.

When I first announced to my family in August that I was going to eat meat for 30 days, the only real reaction I got was from my mother, who was convinced I would become violently ill. Granted, the stretches of time I spent in her bathroom on September 1 did nothing to assuage her fears. Yet I’d be lying if I said I didn’t like being a carnivore for a month. I like steak, and 30 days of almost nothing but meat did little to ruin my enjoyment of it. I relished the simplicity of mealtime, despite the challenge of finding diet-friendly options on certain restaurant menus. (Socially, too, it could be a bit awkward; several times I had to explain to curious onlookers what lipase was.) Once I figured out my bowel troubles, continuing with the diet was a cinch. Aside from my slightly elevated fasting-glucose levels, my blood pressure and weight both remained normal.

I relayed this to Baker when we spoke at the end of September. Even then, he told me, I was looking at the diet the wrong way.

“We have to realize we’re not individual lab data—we’re an entire complex system,” he said. “The more important lesson here is to realize that meat is human food, human nutrition, and it’s probably what we need to make the basis of our nutrition.”

Since completing my 30-day experiment, I’ve become more methodical about what I eat, returning to foods I’ve long enjoyed, like broccoli, rice, and black beans, and adding others I rarely ate in the past, like asparagus and sweet potatoes. I used to eat a sandwich for lunch, but I’ve abandoned that, only because it made me sleepy, which led me to drink more coffee. The clarity I gained from eating a limited diet has made me more discerning. In December, I ate pizza for the first time in months, but I didn’t feel bloated, groggy, or sick—probably because I had two slices instead of six.

“I’m always up for someone who finds a new eating pattern and tailors it to their own needs,” Gardner told me. “I truly believe that there isn’t one diet for everybody.”

There certainly isn’t for me. I don’t think I will ever go full carnivore again. But for one month, I was very deliberate about the food I put into my body. I thought about how it was prepared. I made sure I ate it in the right quantities. I limited how much my work schedule interrupted the meal patterns I was establishing. Now when I sit down to dinner, I eat what I need. I’m less tired. I’m more active. I still eat a steak every now and then. And I feel good.

You May Also Like

WHY ELECTRIC TRICYCLES FROM CHINA ARE TRANSFORMING GLOBAL TRANSPORTATION: A GUIDE TO CHOOSING THE BEST MODEL

December 31, 2024

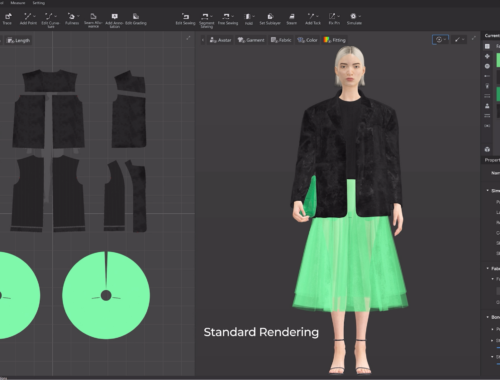

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025