We're Inching Toward Equality for Women in Sports

There’s been a recent wave of new policies that support female athletes, with benefits like equal prize money, salary minimums, and maternity leave. Are these measures enough?

As the women’s professional-cycling season kicks off, all eyes will be on Lizzie Deignan. The former road world champion and 2012 Olympic silver medalist has her sights set on the 2019 UCI Road World Championships in September—which will run through the streets of her home county of Yorkshire, England—and, ultimately, the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo.

But Deignan won’t be on the starting line of the first or even the second race of the season. In fact, she likely won’t kit up until June—roughly nine months after giving birth to her first child.

That the 30-year-old British cyclist is plotting a return to the highest levels of racing is something even she didn’t expect. “I thought motherhood would be the end of my career,” she says. There aren’t many women in road cycling who have successfully combined being a mother and an athlete. Plus, she didn’t think it was feasible to step away from the sport and then come back. Many contracts contain clauses that allow for termination if a rider becomes pregnant. “I never thought I would be in a financial position to take a year off,” she says. After announcing her pregnancy in March 2018, Deignan and her team, Boels-Dolmans, mutually parted ways.

Deignan knew that news of her pregnancy might limit her professional options, but there was one team eager to sign her. Trek, the powerhouse U.S.–based bike company, wanted to invest in a women’s program alongside its men’s WorldTour team—and it was interested in bringing Deignan on board. “She’s an absolute champion of the sport, on and off the bike, and she can bring a whole organization to another level,” says Tim Vanderjeugd, Trek’s director of sports marketing. “The news of her pregnancy didn’t change our view at all.”

“I was really surprised Trek approached me, and their offer reflected my value as an elite athlete at my best, rather than a risk because of my pregnancy,” says Deignan. “They effectively covered my maternity before I even began racing for them.”

For Deignan, the stage is set for her return to racing. And soon other professional cyclists on the women’s tour won’t have to worry about taking time off to start a family or whether they’ll lose their salary if they make that decision: in November, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), the world governing body for cycling, announced new standards for its contracts for Women’s WorldTour riders. Beginning in 2020, female athletes will be entitled to a three-month paid maternity leave (plus an additional five months of leave at 50 percent of their salary) as well as a minimum salary of approximately $17,000 (still less than half the men’s professional minimum), which is slated to increase annually to reach roughly $34,000 by 2023. “I’m happy that [these policies] have been put in place. It shows that women in cycling are professionals, and the right of women to start a family doesn’t limit their careers,” Deignan says. “The fact that the UCI recognizes this is big.”

“Maternity leave is a basic right for every woman. It shouldn’t be different if you’re a professional athlete,” says Iris Slappendel, a retired pro cyclist and the executive director of The Cyclists’ Alliance, a women’s professional cycling union that was launched in 2017. “When women start to think about starting a family or not, when there is a minimum salary and good regulations on maternity leave, it’s better for riders,” she says. For young racers, it positions cycling as a viable career.

The new investments and measures in professional women’s cycling are a sign of changing times in a sport that has historically been dominated by male athletes. And it mirrors the movement of other sports that are also nudging the bar toward gender equality. This year, two of ultrarunning’s marquee races implemented a process for women to defer entry due to pregnancy. Women who are selected as entrants to the Western States Endurance Run or Hardrock 100 and become pregnant before race day can now postpone entry for up to three years. However, runners who defer will still need to meet all the standard application rules and requirements for each race. At Western States, women who become pregnant or give birth during the qualifying period can opt to skip up to three lottery cycles without losing their status. (In February, Western States also unveiled a new policy regarding transgender athletes.) In a sport that has been called out for its underrepresentation of women, with race-qualification requirements that reinforce these low participation rates, these pregnancy-deferral policies are a concrete step toward supporting female ultrarunners. (Major road marathons like Boston and New York City do not offer pregnancy deferrals.)

“We are getting more and more women who are interested, and it’s very hard to get in,” says Dale Garland, race director of Hardrock 100. “Our sport is so time intensive and takes a huge commitment. This [policy] is trying to acknowledge the value of being a mother and not putting your entry to Hardrock in danger if you become pregnant.” Garland says that the policy also fits the ethos of the Hardrock community and the board of directors’ desire to ensure that the race is inclusive. He hopes these changes will have a trickle-down effect and encourage more women to participate in the sport.

Surfing, another sport where women often come second to men, has begun to take steps that address its unequal treatment of female athletes. The World Surf League (WSL) was forced to address the sport’s gender pay gap after a June 2018 photo of the male and female winners of a junior surf contest in South Africa plainly revealed the discrepancy on the winner’s giant checks—roughly $565 to $280. Three months later, the WSL announced it would award equal prize money at its events starting with the 2019 season.

“As athletes, it shows that they value what we do. We dedicate time and energy just as much as the men on tour, and we’re now being rewarded for that,” says Stephanie Gilmore, a seven-time world champion. “To be part of a sport that has a governing body that wants to set the standard that equality should be normal, it’s an inspiration and motivation to get out there, to be a great leader, and to win titles.”

Recently, female surfers have been given a better platform to perform, too. In the past, while the men’s tour has competed on the best waves in the world, the women have been relegated to lesser spots and, at combined men’s and women’s events, lesser conditions. Last year’s women’s tour schedule saw the inclusion of world-class breaks like Keramas in Bali, Indonesia, and the return of Jeffrey’s Bay in South Africa, arguably one of the most pristine right-hand point breaks in the world. On the Big Wave Tour, women have finally been invited to compete at Mavericks in Northern California, after nearly 20 years of advocacy.

Policies regarding pay parity, pregnancy, and maternity leave aren’t just nice-to-have concessions. They begin to professionalize women’s sports and foster safe and fair working conditions, creating an environment that allows for equal opportunity—and success.

Runner Stephanie Bruce has benefited from a team that embraced her identity as a professional athlete and a mother. Her sponsor, Hoka One One, supported her through the birth of two children with no stipulations on when she needed to return to racing. Organizations like the New York Road Runners recognize her role as a parent, too. For example, her contract to run the 2018 New York City Marathon included payment for her children’s travel expenses.

Bruce returned to the sport in 2016, after taking two years off. Rather than motherhood symbolizing the sunset of her days as a professional runner, Bruce considers herself in the prime of her career: she ran a personal-best 2:29:20 for second place at the California International Marathon in December, sliced five seconds off her 5K personal record in January, and qualified for her second world cross-country team in February. “Everyone has been on board,” she says. “I was allowed to pursue my crazy dreams.”

Equal opportunity was also part of the motivation behind Trek’s move to start a women’s team. Vanderjeugd and executives at the company believed it was the right thing to do. Many professional women hold down part-time jobs, share housing, and pay for travel expenses out of their own pockets in order to compete, drawing attention away from their focus on training, racing, and recovering.

“We want these riders to be real professional athletes,” says Vanderjeugd. That means paying a living wage and offering resources like training camps, mechanics, equipment, clothes, and soigneurs on par with the men’s team. “On the men’s side, these are the basics. But on the women’s side, they’re a luxury,” says Vanderjeugd. “Our hope is that we won’t be the only team doing this. We hope that other teams will follow suit.”

While these initiatives are a long-awaited step in the right direction, there’s still a long way to go to achieve gender parity in most sports. “We should acknowledge when progress has been made but also all the spaces where work still needs to be done,” says Cheryl Cooky, associate professor at Purdue University and coauthor of No Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport and the Unevenness of Social Change.

Take the push for a minimum base salary for cyclists, for example. Only those riding for WorldTour teams—five of the 46 UCI women’s teams—are eligible for the new maternity and salary regulations. Non-WorldTour teams are left to decide what protections and pay to offer their riders. “It creates a two-tiered system,” says Slappendel. However, not all teams can afford to pay a minimum salary or provide resources like Trek. Some cycling advocates fear that imposing greater regulations will force some teams to fold, potentially reducing the overall opportunities for women to ride at a professional level.

Equal prize money, too, doesn’t tell the full story. It’s a public-facing number and an easy way for leagues and sponsors to tout their commitment to all athletes. Yet it represents only a portion of what athletes earn from their sport, which, in addition to salary, can include sponsorships and media opportunities—areas where women are still likely to make less than men.

Of course, there’s also a long history of structural and cultural barriers that stand in the way of women’s success in sport. Lack of media exposure is one of the biggest factors. According to the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport, 40 percent of all athletes are female, but female athletes receive only 4 percent of media coverage. “It creates a chicken and egg scenario. If you’re not covering women’s sports, you use that to justify not paying women as much or giving them as much support. But if there isn’t media coverage, people don’t tune in and ratings are low, so media doesn’t cover it,” Cooky says.

Female athletes also continue to struggle against stereotypes that may discourage their participation in sports in the first place. For example, our society celebrates brute power, strength, and speed centered around male bodies, leaving little room for alternative notions of athleticism. Plus, women still shoulder a disproportionate share of labor in the home and family, making it hard to dedicate the time and energy to excel athletically.

If we really want to level the playing field for female athletes, then we need to expand the conversation from gender equality to gender equity. Even if female athletes are awarded the same prize money and sponsorship dollars and are allowed to participate in the same competitions as men, as long as women must negotiate more obstacles to even get to the starting line for these opportunities, it’s not equal footing. Until there’s infrastructure in place that gives women the opportunity to dedicate the time and resources to excel in sports, and to be compensated fairly, women will always be playing catch-up to men.

“We cannot allow for regression,” Deignan says. “We cannot lose new races and initiatives like equal prize money and TV coverage. We must keep pushing.”

You May Also Like

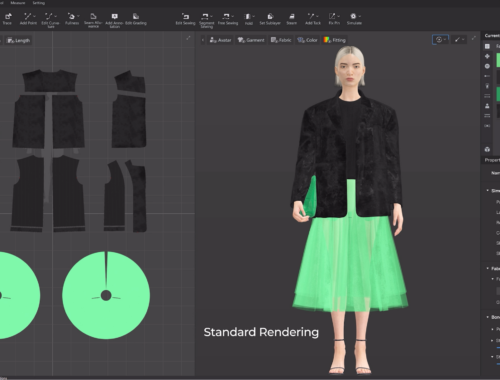

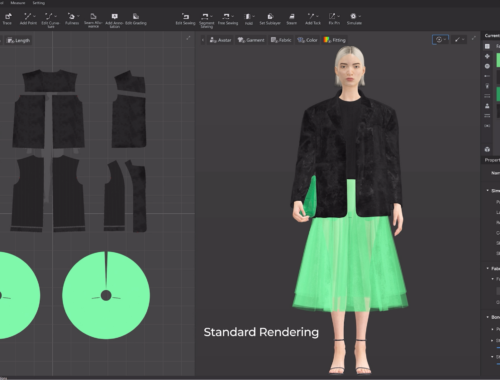

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

AWS Weather Station: Monitoring Environmental Conditions with Precision

March 17, 2025