Washington's Bold Plan to Save Its Orcas

>

The last time I saw Scarlet alive, rain from a dismal September sky was pattering the Salish Sea. Despite the weather, dozens of people lined the cliff of San Juan Island’s Limekiln Point State Park, the best place to watch killer whales from land. It was as if they’d turned out to pay their respects to a funeral train.

I was on a NOAA Zodiac with a team that included a University of California at Davis wildlife veterinarian who was hoping to dose the sick three-year-old orca with an antiparasitic solution. As we approached Scarlet, she was struggling to keep up with her mother and three older siblings, all members of the Pacific Northwest’s critically endangered Southern Resident killer whales. The vet shot two darts filled with medication, but up close it was obvious that this and the other unprecedented attempts to save Scarlet weren’t going to be successful.

Scarlet’s once white eye patches had turned bilious orange, and instead of highlighting the Rubenesque form of a healthy killer whale, they wrapped tightly around the shape of her blubberless skull. She’d lost so much of her buoyant, insulating fat that it looked like just surfacing for air was an effort.

Less than a week later, after her mother had been seen several times without her, Scarlet was officially declared dead. The little orca likely just slipped away and sank forever into the cold, green water.

Losing Scarlet dropped the Southern Resident’s population to 74, its lowest level in 35 years. Since she was a female with breeding potential, her death nudges the whales that much closer to extinction.

The Southern Residents are sliding toward oblivion for three main reasons: fish, fish, fish. Chinook salmon makes up at least 80 percent of their diet, but many Chinook runs are also endangered. Man-made noise from vessels makes it harder for the orcas to communicate and hunt for what few fish are left. When they do catch a fish, it’s loaded with industrial and agricultural toxics.

The attention garnered by Scarlet and, last summer, by her podmate, Tahlequah, who carried around her dead calf for 17 days, spurred some government officials to action. Canada curtailed salmon fishing in several known orca feeding grounds, continued a noise-reduction program for ships heading to and from Vancouver, earmarked some funding for salmon recovery, and finally matched the U.S. requirement to stay at least 600 feet from killer whales.

On the Washington State side of the Salish Sea, governor Jay Inslee formed the Southern Resident Killer Whale Task Force and challenged the group to come up with a package of “bold” proposals to save the orcas.

After a series of meetings and surveys that generated more than 18,000 public comments over six months, the task force delivered its report and 36-point plan on November 16. As an in-depth primer on the Southern Residents and Chinook salmon and the complex anthropogenic impacts that both have faced for more than 100 years, the report is an excellent read. As a set of actions to save both linked species, it’s a strong push in the right direction including, as advertised, some bold and contentious ideas, such as a moratorium on whale watching the Southern Residents.

Governor Inslee, who’s eyeing a run for president in 2020 on the strength of Washington’s burgeoning green economy and his attention to climate change and other environmental issues, kept up the task force’s momentum by turning its recommendations into more than $1 billion worth of items in the state’s proposed 2019–21 budget, which will be up for approval with the legislature this spring.

Much of that funding would go to enforce existing regulations protecting habitat and to continue or accelerate restoration projects, all aimed at increasing Chinook salmon, because no Chinook equals no orcas. It also includes money to support the sounds-good-at-the-end-of-the-bar fixes, such as culling seals and sea lions and increasing salmon-hatchery production.

Sea lions will die because they’re smart enough to take advantage of the dam bottlenecks we created that block spawning salmon, serving them up at all-you-can-eat buffets for the pinnipeds. People forget that, to protect salmon populations, Washington long had bounties on seals and sea lions ($1 and $2.50 a scalp, respectively, back in 1903; $8 a nose in later years, before the bounties finally ended in the 1960s), and all that time the Chinook numbers still crashed due to overfishing and habitat destruction.

The damage and disruption we’ve done to natural systems out West means we do need salmon hatcheries in the short and medium term, even though they threaten wild-run fish via competition and genetic dilution. (It’s the wild salmon that reproduce more successfully and have the resiliency needed to better face climate change.)

Along with the bounties on predators, we also forget that before we adopted the Northwest’s orcas as beloved icons, they were killed by fishermen because they, too, competed for salmon. The orcas were also shot by the military just for target practice. And we had no problem letting them be rounded up, driven into nets by explosives, calves separated from mothers, and shipped off to marine parks to entertain us.

Our attitudes toward orcas have evolved quickly, but only after we set in motion a clear path to extinction for the Southern Residents, who can’t evolve fast enough to save themselves from us.

Reading through the task-force proposals and governor’s budget, what’s apparent is that nearly all the beneficial orca and salmon actions will also serve to create a healthier, more productive environment for humans. Cleaning up toxics, preventing oil spills, letting rivers run more naturally, rebuilding fish stocks, and other steps to restore the ecosystem are all no-brainers, even if you don’t care about killer whales. The Washington State legislature should see it that way when it votes on the budget.

This billion dollars is not going to save the orcas, though. That will take decades of continuous effort at the state level as well as federal action on dams and mixed-stock salmon fishing outside Washington State waters. But it’s definitely movement in the right direction and a sign that the people of Washington are willing to invest, and maybe even inconvenience themselves, to help save a bellwether species that’s dying in order to show us what we’re doing to ourselves.

The task force’s stated recovery goal is to add ten Southern Resident orcas in ten years. Around the same time Scarlet was declared dead, aerial photos showed that one female from each of J, K, and L pods that make up the Southern Residents was pregnant. On January 11, researchers spotted what they estimate to be a three-week-old calf with one of those whales, L77, Matia. Designated L124, the baby looked healthy, and all three pods came together that day in a “superpod,” which is a gathering of the clans accompanied by lots of socializing and playing—something we’d recognize in our culture as a celebration.

Unfortunately, according to the Center for Whale Research, two adult orcas, including Tahlequah’s mother, J17, look thin, and there’s serious concern whether they’ll make it through the winter. Despite the federal government shutdown, NOAA just recalled its West Coast marine mammal stranding coordinator on an emergency basis, and wildlife veterinarians are making plans to conduct a health assessment on the two whales as soon as possible.

With two orcas in poor health and the Southern Residents’ recent rate of failed pregnancies, the odds are long against the population growing more this year. But then the odds weren’t good that Tahlequah would carry her dead calf around long enough for the world to take notice of the orcas’ plight, or that Scarlet could hang on long enough to ensure that the public and political will was strong enough to act.

The new baby and new actions means there’s hope for the Southern Residents. Hopefully it’s not going to take a continual procession of dead whales to keep us pursuing positive steps to fix the ecosystem both we and the orcas depend on.

You May Also Like

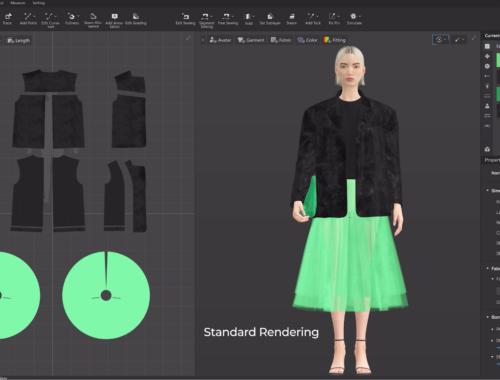

**AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability**

February 28, 2025

Wind Speed Measurement Instrument: An Essential Tool for Accurate Weather Monitoring

March 19, 2025