Want Kids to Care About Conservation? Take Them Rafting

Bobby Kennedy Jr. has spent a lifetime protecting rivers, an ethos born on childhood expeditions

On a Tuesday morning in late October, Bobby Kennedy Jr. was riding a dusty, decommissioned school bus through the Rio Grande Gorge in northern New Mexico. The bus, like all river buses, had bad shocks and half-drifted, half-bounced along the narrow turns. A gray-bearded river guide named Cisco stood up in the front, swaying in time with the bus.

“Raise your hand if you’ve never done this before!” Cisco called out to the 20 or so passengers. We had come to raft a four-mile section of river with Kennedy, whose global conservation organization, Waterkeeper Alliance, had just named the Rio Grande to its list of more than 350 protected rivers worldwide. Behind me, Bobby Kennedy’s hand shot up.

Cisco grinned mischievously. “So, the most important thing is keep your hands inside the bus windows, or else they might get chopped off!”

Slouching sideways in his cracked vinyl seat, Kennedy lowered his hand and mumbled sheepishly, “Oh, I thought he was talking about rafting this river.” A few moments later, when we arrived at the boat launch, two guides handed out life jackets. Kennedy put his on, fumbling with the zipper, while the guides tugged at the side straps to adjust the fit. Kennedy laughed. “It takes four people to put on my life jacket,” he said, beckoning to two passengers nearby. “You want to help?”

Kennedy’s self-effacement is deceiving. He’s been rafting since he was 12, when his father, the late Senator Robert F. Kennedy, started taking him and his siblings on trips down all the big western rivers. In the decades since, Kennedy, 63, has kayaked whitewater all over the world and, through his work as an environmental lawyer, established himself as an ardent river steward. As legal counsel to Riverkeeper in New York, he helped restore the Hudson into a living river. He fought against proposed dams on the Bio Bio in Chile. (“We blocked all but one, but that one destroyed the river,” Kennedy said sadly. “I would cry if I went back.”) Most recently, he helped defeat a dam on Chile’s Futaleufu.

The October morning was bright and blue, but the sun still hadn’t crawled down the 800-foot-high canyon walls, and it was not quite 50 degrees. Kennedy wore a pair of perfectly faded Levi’s 501s, a neoprene wetsuit top he’d put on over his Waterkeepers T-shirt, and a borrowed Arc’teryx cap pulled low over his ears. Kennedy climbed into the raft while Cisco oared us off the bank and into the gentle, bottle-green current.

The Rio Grande flows 1,885 miles from its source in the San Juan Mountains in Colorado to Brownsville on the Gulf of Mexico, though by the time it reaches the delta, it’s a trickle of its former self. The section we floated through, in the rugged Rio Grande Gorge, was designated a Wild and Scenic River in 1968, one of the first U.S. rivers to receive federal protection. Now it’s part of the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument, one of the country’s newest and most embattled national monuments, currently under review by the Trump administration.

Waterkeepers has its work cut out for it. Together with the environmental group WildEarth Guardians, it will work to defend the river from dewatering, pollution, and climate change. The lifeblood of the Southwest, the Rio’s water is in high demand from farmers and ranchers and thirsty municipalities that have quadrupled in size since the antiquated Rio Grande Compact was signed in 1938, parceling water to the three states through which it runs. Seasonal runoff is restricted by 20 dams along its length, and climate change is predicted to reduce flows by 20 to 25 percent over the next century. Upstream, copper mines jeopardize the water quality; that very morning, Cisco told us, a team of scientists from Los Alamos National Laboratory had launched a four-day expedition to test the river for toxic runoff.

Kennedy is clearly at home on moving water. He was soon draped over the raft, his feet propped up on the bulwark, hands clasped behind his head, watching the basalt walls slide by. Like all river trips, it was an occasion to remember previous river trips—of which he’s had many. There was the time Kennedy rafted the Middle Fork of the Salmon with his father, legendary boatman Dee Holliday, alpinist Jim Whitaker, and astronaut John Glenn. There was the summer camp he ran with his brothers, on the Kennebec in Maine, in the years after his uncle and father were assassinated. There were the outlandish misadventures, like the time the bush plane he was riding in clipped a wing and crashed on takeoff from the Magpie River in Quebec, and a first descent in Venezuela where Kennedy had a near-drowning experience and he and his team had to be rescued by the Venezuelan air force.

“My whole life has been rivers,” said Kennedy, who dates his love of wild places to his childhood roaming free on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and the ponds near his home in Washington, D.C. “I was always out catching tadpoles. My parents never let us inside during the day,” he said. It was, in many ways, a lost, idyllic boyhood. “It’s so hard nowadays to get kids away from screens.” Kennedy takes his kids into the wilderness as often as possible, most recently on a raft trip down the full length of the Green River.

We rounded a bend, startling a trio of ducks in an eddy. “Mallards,” Kennedy said, smiling. The tamarisk and cottonwoods blazed gold, and Cisco pointed out petroglyphs etched onto a small boulder above the river. The sun had warmed the morning, and Kennedy had shed his hat and neoprene. All too quickly, we came to the take-out. No sooner had Cisco pulled the raft onto dry land than Kennedy snapped into action. He had a book to finish writing—his 14th, on foreign policy—and a plane to catch. He posed for a few pictures, ate a couple carrots off the lunch buffet laid out in a plastic tray on the picnic table. The river trip, like the best river trips, had been a respite—all too brief—from the frantic pulse of daily life, but now it was time to rejoin the flow of humanity.

“Stewardship is in the DNA of river people, but we have to get more people out on these beautiful rivers,” Kennedy said, waving his hand at the Rio Grande, easing on toward the bosque and irrigation ditches downstream, and somewhere beyond that, to its beleaguered delta. “You have to see it to save it.”

You May Also Like

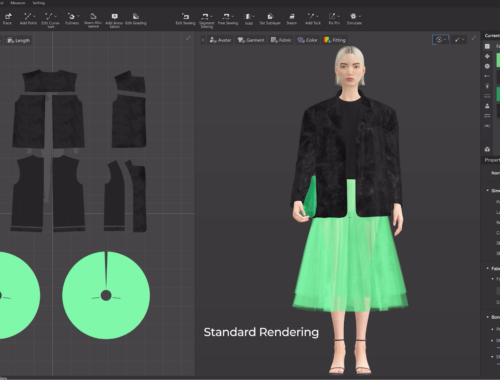

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Sustainability, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025

Dino Game: A Timeless Classic in the World of Online Gaming

March 21, 2025