Track and Field’s Hall of Shame

Every sport has moments it would rather forget

The 2017 IAAF World Championships came to a close on Sunday in London. As with the 2012 Olympics, which also took place in the English capital, the latest installment of the biennial event appears to have been a success. In terms of ticket sales, it was the most well-attended track and field world championships in history: 900,000 spectators turned out in droves to witness the grand finale of the Usain Bolt/Mo Farah era. With Eugene, Oregon, slated to host in 2021, TrackTown USA can only hope to inspire similar levels of enthusiasm four years from now.

Not that the IAAF wasn’t dealt a few wild cards last week. Some were minor, like the streaker who warmed up the track for the finalists in the men’s 100 meters on the eve of the first full day. In the subsequent race, alleged former doper Justin Gatlin won the 100-meter final, causing London Stadium to erupt in boos and IAAF president Seb Coe to admit that a Gatlin victory was hardly “the perfect script.” A few days later, gold medal contender Isaac Makwala was involuntarily barred from the men’s 400-meter final on the grounds that he had contracted a contagious virus—a decision that BBC commentator Michael Johnson suggested was “horribly wrong.” In the men’s 4×100 meters, Usain Bolt’s illustrious career came to a disappointing end as the sprinter suffered a cramp in his hamstring and crashed to the track in agony. His team blamed event organizers for allowing too much time to pass between warmup and the start of the race.

Embarrassing as these moments were, the sport of track and field has seen much worse. Here are some historical highlights.

Down Goes Decker

To a veteran athletics enthusiast, the boos that rained down on Justin Gatlin after the men’s 100-meter final might have brought back memories of another incident when the crowd was less than charitable to an athlete on the track. In the women’s 3,000 meters at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, Mary Decker was the clear favorite—both to win the race and in the hearts of those in the stands. After all, Decker was the local girl, having grown up within 50 miles of the Los Angeles Coliseum. South African Zola Budd, meanwhile, had grown up on the other end of the world.

Competing for Great Britain (South Africa was barred from the Olympics because of its apartheid regime), Budd ran barefoot and hung at Decker’s side for the first half of the race. With just over three laps to go, Budd cut in front of Decker, who, moments later, would clip the South African’s heel, trip, and tumble off the track, injuring herself in the process. The degree of Budd’s culpability for taking out the hometown favorite remains debatable (watch the race below), but to the thousands who were present that day, Budd was the villain. Such was the intensity of the audience’s booing that it may have affected her race; she faded badly on the last lap and finished in seventh place. “The main concern was if I win a medal,” Budd said in a 2009 Runner’s World article, “I’d have to stand on the winner’s podium, and I didn’t want to do that.”

Marathonus Interruptus

The marathon-themed nightmare isn’t uncommon among dedicated runners, but most are spared the experience in waking life. Vanderlei de Lima wasn’t so lucky. With less than five miles to go in the men’s marathon at the 2004 Olympics, the Brazilian was having the race of his life. On the streets of Athens, de Lima was leading by half a minute when he was accosted by eschatologist wacko Neil Horan—the Irish “priest” whose other contributions to the world of sport include running onto a Formula One track toward oncoming traffic. A fan was able to help free de Lima from his kilted tormentor, but the attack cost the Brazilian a good portion of his lead, and he was noticeably shaken up afterward. De Lima ended up finishing third and was awarded the Pierre de Coubertin medal for sportsmanship in addition to the bronze. At the time of the attack, an Australian TV commentator spoke for most: “That is just the worst thing I have ever seen at the Olympic Games.”

The Steeplechaser You Love to Hate

One of the unexpected highlights of the just-concluded world championships was Hero the Hedgehog, perhaps the most versatile mascot in history. Fortunately, Hero never entered the crosshairs of steeplechaser and self-styled enfant terrible Mahiedine Mekhissi-Benabbad. Following his win at the 2010 European Athletics Championships, the Frenchman made the mascot kneel in front of him, and then promptly pushed him to the ground. At the European Championships two years later, Mekhissi-Benabbad did it again, this time violently shoving what turned out to be a 14-year-old girl. Lest anyone should think Mekhissi-Benabbad’s résumé is limited to roughing up costumed cheerleaders, he is also known for engaging in post-race fisticuffs with fellow athletes, as well as premature shirtless celebrating. After a fourth-place finish last summer in Rio, Mekhissi-Benabbad helped get bronze medalist Ezekiel Kemboi disqualified for (literally) one misstep during the steeplechase.

A Violation of Privacy

The next development in the controversy surrounding Caster Semenya—the allegedly hyperandrogenic South African 800-meter runner who won the gold medal in London on Sunday—is expected to come sometime in September or October. At that time, the IAAF will once again attempt to convince the Court of Arbitration for Sport that athletes like Semenya must artificially reduce their atypically high testosterone levels in the name of a “level playing field.” “This is an incredibly sensitive subject,” IAAF President Seb Coe told the Guardian last week. Unfortunately the IAAF didn’t do enough to treat it as such when, during the 2009 World Championships, the organization revealed that Semenya had been asked to undergo a gender verification test, leading to a media frenzy. The disclosure was widely condemned as a careless violation of an 18-year-old’s privacy (sports scientist Ross Tucker recently referred to Semenya’s “outing” as a set of “almighty screwups”), the fallout from which the IAAF is still dealing with today.

Tainted Golds

All doping scandals hurt professional athletics, but when an Olympic gold medalist is involved, the pain is most acute. Nothing is more delegitimizing for a sport than when the athlete standing on the top of the podium in the premier competition turns out to be a fraud. Unfortunately, this regrettable circumstance has only become more common in track and field. The first high-profile case came at the 1988 Games in Seoul, when Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson was disqualified for steroid use a few days after winning the 100 meters and setting the world record. More recently, U.S. sprinter Marion Jones had her remarkable five-medal (three gold) performance at the Sydney Games stricken from the record after she confessed to steroid use in 2007; her abrupt retirement from track and field at the time was followed by a six-month jail sentence. No fewer than six track and field athletes from the 2012 London Olympics have since been stripped of their gold medals. Last April, Jemima Sumgong, winner of the women’s marathon in Rio, tested positive for EPO—prompting LetsRun.com co-founder Robert Johnson to ask, “What’s the point of being a fan anymore?”

11 Great Deals at REI's Winter Sale

The Death of Road Riding

You May Also Like

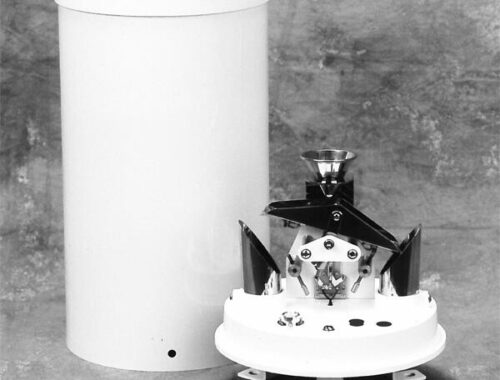

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025

Automatic Weather Station: Real-Time Environmental Monitoring and Data Collection

March 14, 2025