This New Fund Will Help Climbers Cope with Death

>

“Hayden and Inge died.” (October 8, 2017)

The text lit up my phone late one night, four words that seared themselves into the back of my skull. The texter, my friend Leslie, called a few minutes later to relay the details. Renowned climbers Inge Perkins and Hayden Kennedy got caught in an avalanche while skiing in Montana. Perkins died, and unable to bear the loss of his love, Kennedy returned home and killed himself. I had met Inge a handful of times, a sweet and lovely young woman who quietly climbed circles around everyone. I didn’t know Hayden, but I had followed his impressive career for almost a decade and knew him to be a thoughtful and brilliant person.

After getting off the phone, I sat in the dark of my van, wondering what to do with this pain. It was an ache that made me uncomfortable by its very existence. I didn’t know either of them very well; do I even have a right to be this upset? Is my sorrow valid? Parked in the middle of the woods just south of Meyers, California, I was alone and didn’t know anybody within a six-hour drive. It was after 11 p.m., too late to call other friends. Hayden and Inge were so loved by so many. All I could do was get in bed and cry. As much as I wanted the night to be over, I dreaded waking up to the heartbreak that would be sweeping the rest of our little climbing community.

“Did you hear about Savannah?” my friend Shelma asks. I say no, assuming Sav has done something super cool I should know about. Shelma continues, “She died in a climbing accident yesterday.” (March 29, 2018)

I sat in front of my laptop at Black Sheep Coffee Roaster in Bishop, California, the work I’d come there to do now forgotten. Savannah Buik, a 22-year-old climber from Chicago, was leading a route at Devil’s Lake State Park in Wisconsin. She fell, and the two pieces of protection she placed came out. She hit the ground and died on impact.

I met Savannah six years ago in Horse Pens 40, Alabama, at a boulder problem called Genesis. As the only two girls among a sea of climber boys at the crag that day, she and I struggled with the problem’s huge crux move. In between burns, I overheard her telling a friend about her efforts to get better at climbing writing, and that she hoped to intern at Climbing magazine one day. At the time I was an editor there, and the person in charge of hiring interns, so I mentioned this to her. Even though she was only in high school, I admired her stoke and drive. We talked for a long time at that boulder, the conversation carrying over into countless emails exchanged for years afterward. She would send me links to her recent work; I would send her feedback and encouragement.

After hearing the news, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I got up and walked around aimlessly outside. I called a few friends, then my mom. I walked back in the coffee shop and stopped near the cash register, unsure of what I was doing there. Shelma approached me, and I just put my head on her shoulder and cried.

“Can I call you? One of my best friends from Bend died yesterday in a climbing accident at Smith.” (April 11, 2018)

Another text, this one from my friend Bobby. His buddy Alex Reed was unroped on easy terrain, scoping new-route potential in Smith Rock. The 20-year-old climber slipped and fell 300 feet. On the phone, Bobby told me about Alex, a loving and genuine person who’d become a bright fixture in the Bend climbing community. Unsure of how to deal with his sorrow, Bobby decided to drive ten hours from Bishop to see Alex’s Astrovan one more time, to go to Smith Rock and be with mutual friends. He texted me again a few days later: “What’s one thing you would tell someone who just lost a friend? People are really hurting.” I responded as best I could—say you’re sorry, listen, be there for them—but it felt pathetic.

Because what do you say? How do you tell someone you’re sorry a hundred times and not feel like a useless piece of shit? How do you deal with your own grief, let alone someone else’s? We do what we can by turning to friends, posting tributes on social media, and analyzing what contributed to the misfortune. Maybe if we look at the scenario and what went wrong, we can avoid the same fate. Death doesn’t discriminate, but it sure does seem to like climbers.

Like a building thunderstorm, the risk of death follows climbers throughout our vertical lives. At first we view the clouds from afar—we’re aware of their presence but they don’t affect us directly, like a well-known alpinist disappearing in the big mountains or a rappelling accident at a faraway crag. Time passes, you climb more, and the clouds grow larger and darker with each “Oh, my buddy was friends with her…” Then crack—lightning strikes, the bottom falls out of the sky, and death strikes someone close to you.

Pro climber Madaleine Sorkin has been climbing for almost two decades, but a slew of accidents last year hit really close to home. In August, Sorkin and climbing partner Kate Rutherford helped a woman out of the Wind River Range in Wyoming after the woman’s partner died in a rappelling accident. Kennedy, whom Sorkin was close with, and Perkins died in early October, and a few days later, Quinn Brett, a longtime climbing partner of Sorkin’s, took a 100-foot fall on El Capitan and was paralyzed from the waist down.

“There was raw grief for me with these losses and changes,” Sorkin says. “I felt stunned and depressed. I wasn’t finding climbing fulfilling and didn’t know how to process the pain that I was feeling related to climbing. And as I looked around our climbing community I didn’t see much guidance or resource for how to process this grief.”

So Sorkin teamed up with the American Alpine Club to create the Climbing Grief Fund, a resource for climbers affected by the death. The idea is to help the climbing community, as a whole and on an individual level, cope with trauma and grief. It will start with a grief resource webpage, individual counseling grants, and group therapy sessions at climbing events, like the nationally touring festival AAC Craggin’ Classics—all coordinated by the AAC with plans to expand as more funding comes in.

Right now the fundraising page’s goal is set at $12,000, and Outdoor Research has agreed to match the first $5,000; they are hoping to grow the fund in the coming years through individual/private, corporate, and organizational donations. To raise money for the Grief Fund, Sorkin and climber Mary Harlan have planned a 24-hour link-up of three big routes in Colorado’s Black Canyon of the Gunnison, calling the attempt 24 Hours into the Black. Originally she was going to attempt the link-up in late May, but a large portion of the canyon was closed indefinitely due to a shifting football-field size flake in the area called The Flakes. The climb has been postponed to September.

The only way to truly avoid the tempest of death is to stop climbing altogether. Since most of us won’t stop climbing, eventually the thunder and lightning will find us. The aim of the Grief Fund is to provide some shelter from the storm, just enough protection to get us through the heaviest part of the downpour and into the bright sunlight that follows.

You May Also Like

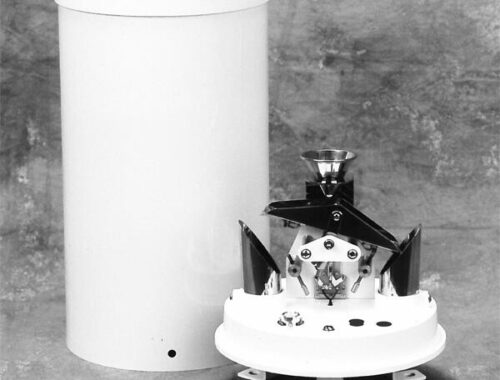

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025

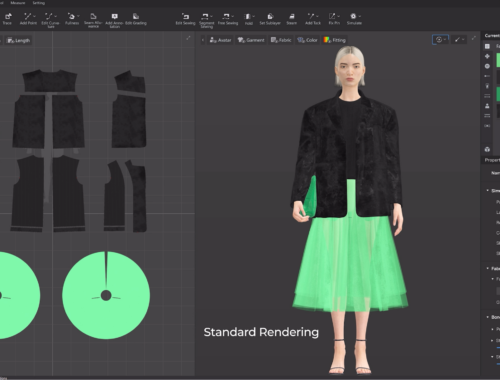

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

February 28, 2025