There’s New Data on the Cardio vs. Weights Debate

A mixed workout program produces the best heart health outcomes, a new study finds

Back in 2011, I published a fitness science book with the enigmatic and highly regrettable title Which Comes First, Cardio or Weights? The main problem with the title was that it meant that every one of the dozens and dozens of radio interviews I did following its release started with the obvious question about whether cardio or weights is more important—to which my answer was something along the lines of “Well, both… or neither… I mean, it depends.” Then there would be a long pause, punctuated in my imagination by the clicking of thousands of web browsers snapping shut as listeners decided they didn’t need to order this book after all.

(The other option was to explain that the title wasn’t actually about which was better, but which you should do first, based on the results of new molecular signaling research. Okay, the host would gamely reply, so which should we do first? “It depends.”)

These painful memories came flooding back with the publication of a new study in PLOS One that tackles, once again, the eternally contentious question of whether cardio or weights is better. Researchers at Iowa State led by Duck-chul Lee (whose previous epidemiological research I recently wrote about here) put a group of volunteers through an eight-week head-to-head matchup—and the good news is that the results validate my waffling.

I should probably start by acknowledging that there are plenty of contexts where the choice between cardio and weights is perfectly clear. If you want to get really big muscles or lift heavy things, then some form of resistance training is required. If you want to minimize your marathon time, you’re going to need a large dose of sustained aerobic training. But there’s a broad and murky middle ground where people have hazily defined goals like being healthy, feeling good, and living for a long time. Which one triumphs then?

The particular situation investigated in the new study involved a group of 69 older adults, with an average age of 58, all of whom were at elevated risk of heart disease because they were overweight, had high blood pressure, and didn’t exercise regularly. They were then split into four groups: a control group that didn’t exercise; a cardio group that did treadmill or indoor cycling workouts; a weights group that did a standard circuit of 12 resistance exercises; and a combination group that did a mix of both. The latter three groups exercised three times a week for an hour at a time, for a total of eight weeks. The combo group did 30 minutes of cardio and 30 minutes of weights.

Each of the three exercise groups had its advantages. The cardio group had the biggest increase in aerobic fitness, and was also the only group to see a significant decrease in body weight (by 2.2 pounds) and fat mass (by 2.0 pounds). The weights group had a significant increase in lower body strength, as well as a slight decrease in waist circumference.

But the main goal of the study, given the participants, was to reduce heart disease risk. The primary outcome the researchers were interested in was blood pressure, and the only group to see a significant reduction in blood pressure was the combination group—though it was only a small reduction of 4 mmHg in diastolic pressure (the smaller of the two numbers that describe your blood pressure). This group also saw an increase in aerobic fitness, like the cardio group, and increases in upper and lower body strength, like the weights group. And in a composite score of cardiovascular risk, which summed the contributions of blood pressure, cholesterol, lower body strength, aerobic fitness, and body fat percentage, the combo group was the only one to see a significant improvement compared to the control group.

When you read a paragraph like the preceding one, a few alarm bells should go off. With more than a dozen different outcome measures in a study where each group has barely more members than that, you’ll inevitably find some seemingly significant changes. The statistical analysis in this paper did apply a correction factor to account for the large number of outcome variables, but the fact remains that most of the observed changes were relatively small. It’s surprising, for example, that the aerobic exercise group didn’t see any improvement in blood pressure, in contrast with quite a bit of previous research. That’s probably mostly a result of the fact that eight weeks simply isn’t long enough for a relatively moderate exercise program to produce dramatic changes.

So let’s not write these results in stone just yet. I remain confident on the basis of other evidence that aerobic exercise is a powerful way of improving cardiovascular risk factors like blood pressure. Still, the overall pattern here makes sense. Yes, cardio training gives you the biggest cardio boost, and strength training gives you the biggest strength boost. Duh.

But the combination of both may have some unique powers for more general goals like heart health. This doesn’t necessarily imply any sort of mysterious alchemy—“muscle confusion,” say—between the different types of exercise. It may simply be that everyone has a different mix of relative strengths and weaknesses, and everyone responds differently to various types of exercise, so a mixed workout routine ensures that in a large group every individual gets some exercise that hits them where they’re most likely to respond. If you want to improve public health (or if you’re doing a radio interview about your new fitness book), maybe that’s not such a bad place to start.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.

You May Also Like

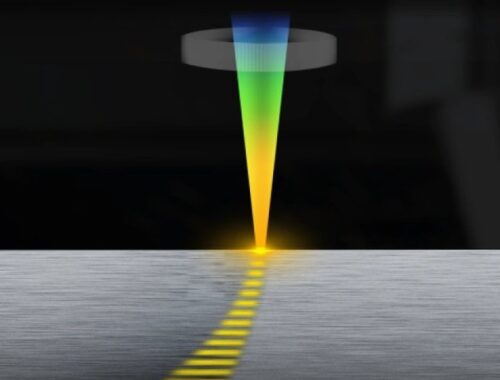

HOW TO IMPROVE PRODUCTION EFFICIENCY OF A LASER PLATE CUTTING MACHINE

November 22, 2024

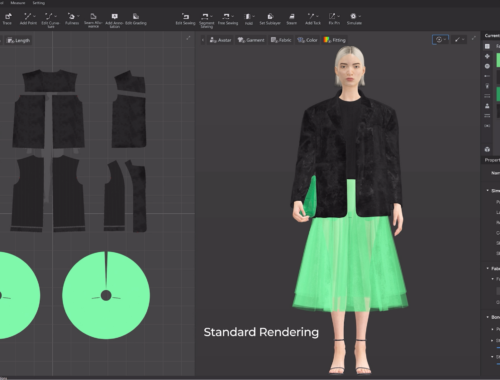

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025