The Worst Thing About Environmentalists

>

Of all the threats that our environment faces, one of the most insidious is voter complacency. According to the Environmental Voter Project (EVP), around 15 million “super environmentalists”—which the group defines as those citizens who rank protecting the planet as one of their top priorities—didn’t vote in the 2014 midterms. That stat baffles Nathaniel Stinnett, founder of the Boston-based nonprofit. “Maybe the environmental movement doesn’t have a persuasion problem,” he says. “It has a turnout problem, and nonvoters are a low-hanging fruit.”

Indeed, the numbers suggest that, as a voting bloc, engaged environmentalists could make a difference. Six out of ten Americans think climate change has a direct impact on their community and believe it is a problem the government should address. So why don’t they take that knowledge—and anger—to the voting booths?

According to Kevin de León, the Democratic president pro tempore of the California Senate, it’s because the environmental movement has a messaging problem. “Historically, climate change and the environment have been aligned with elites,” he says. “We must democratize the issue so everyday families can get access to the latest and greatest green energy technology. It can’t just be a boutique industry for those who have the financial wherewithal.” Messaging around the issue has also been framed as an either-or problem, pitting the economy against the environment, says Sean Casten, an Illinois Democrat running for a House seat next month.

Then there’s the futility factor. It’s hard to convince people their votes will have any impact. “We don’t have rivers catching on fire anymore,” says Emily Norton, executive director of the Charles River Watershed Association and a city council member in Newton, Massachusetts. “When you can’t always smell it, you can’t see it, you can’t taste it, it has to be pretty bad before people act.” The right may have its climate deniers, but the left has its share of climate despair, says Alice Hill, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama and National Security Council member. That despair can be just as dangerous. “When I talk to people about climate change, it can feel quite overwhelming to them,” says Hill, who now serves as a research fellow for Stanford University’s Hoover Institute. “They have a sense of hopelessness. It’s easier to engage on other issues that they can influence.”

In short, the best way to get people to vote for the environment might be to not mention the environment at all. After all, just 4 percent of voters say they want candidates to talk about the environment in the upcoming election, according to a June poll by the Pew Research Center. Even among Democrats, just 5 percent said the environment was the most important problem facing the nation.

Stinnett doesn’t want the EVP to proselytize; he just wants people who already say they care about the environment to show up next month and prove it on the ballot. He has a simple three-part plan to activate environmentally focused voters: emphasize that voting is a societal norm, make them pledge to vote, then remind them close to the election that they promised to vote. The guilt works, according to the group’s 2017 election efforts. When the EVP was able to connect with targeted environmentalists through at least two methods of communication—calls, texts, direct mail, email, in-person canvassing, or digital advertising—voter turnout in that group increased anywhere between 2.8 percent and 4.5 percent. The EVP and its 1,800 volunteers will target 2.4 million environmentalists with poor voting records in Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Pennsylvania this month for November’s elections. In those six states, Stinnett ambitiously expects to add as many as 108,000 people to the electorate through calls, texts, and door-to-door canvassing.

The EVP isn’t alone in this initiative. The League of Conservation Voters will target swing voters with the goal of convincing them that their votes can directly affect their communities, from public land access to clean water and air protections. Pete Maysmith, the league’s senior vice president of campaigns, says he’s targeting four Senate races with $3.1 million and 25 congressional seats with $15 million—four times the amount the league spent in 2012. “We want to turn out all voters who support pro-environment initiatives, no matter if it’s their top priority or at the bottom of their list,” Maysmith says.

Not everyone believes in this if-you-register-them-the-policies-will-come approach. Jamie Henn, a co-founder of climate change advocacy group 350.org, admires the EVP’s efforts but thinks it will take a lot more proselyting to enact progress at the federal level. Groups and individuals who want to see actual laws passed to protect the planet, Henn argues, must build movements among broader coalitions and start iconic fights—like those against ExxonMobil or TransCanada—to get people organized and fired up. “We can’t wait around for politicians to suddenly see the gospel and start preaching it,” he says. “We can do it ourselves and pull politicians—and, by extension, voters—with us.”

The Trump administration’s anti-environmental actions have brought new focus to the movement, Maysmith says. “People are taking to the streets, they’re so concerned,” he says. “Now that we’ve done that, what’s the next thing we can do? Vote.”

You May Also Like

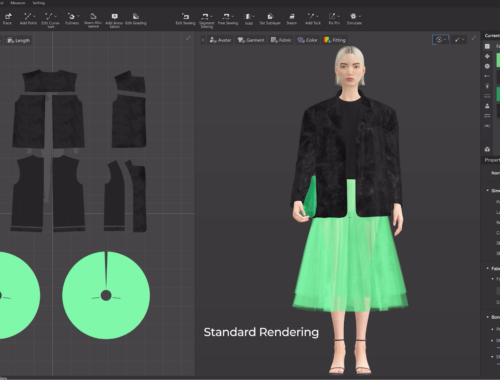

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Sustainability, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025

ユニットハウスのメリットとデメリットを徹底解説

March 20, 2025