The untold story

Author Yang Hao is defying narrative convention with her clever, but discomforting fictional debut, Fang Aiqing reports.

Many of today’s authors write to encourage readers to believe in, and in some cases, even imitate the characters, plots and lifestyles laid out in their stories. However, Yang Hao, in her 30s, is not afraid to make them feel doubt and discomfort.

The readers’ uneasiness drawn from her fictional debut Novel Noir is what convinces her that she has achieved her goal in the way she wanted to shape the atmosphere, linguistic style and characters within her work.

“Who says literature has to bring pleasure?” she asks.

Initially, she saw the rating for her book on douban.com, a popular Chinese book review site, drop before eventually reaching a plateau.

“I think that it was because the readers had projected the illusion of literary and artistic fantasy to my work,” she says.

Obviously, that conclusion is not true, as, in her words, she’s created two characters “with problems”.

In the story, attempting to write a novel, medical student M remains in London after his doctoral enrollment at the University of Manchester.

He wanders around, encounters people and tries to research James Hamilton, the first Duke of Hamilton, out of curiosity about British nobility.

M tries to live like he imagines a writer might, but the process of starting the novel takes a long time.

W, majoring in art history, takes sick leave for half a year and rents an apartment in Mayfair, London, to study, coincidentally, the Duke of Hamilton and his art collection.

Though the two never really meet each other, she experiences things that echo M in some way. Both of these Chinese students in Britain, through their idle stay in London, and also their previous life in Scotland, have been dealing with the inevitable feeling of a void.

It serves the reader well to not expect too much drama, or a traditionally linear unraveling of a literary yarn. The plot is so fragmented that one can start reading from any of the 20 chapters.

“Every time I thought that something would happen, it just stopped abruptly,” commented douban.com user, Ye Ye.

Yang questions what literature and fiction means to us today. She deliberately eliminates a strong narration, considering the fact that visual entertainment, such as movies, TV and games, has already done very well in telling stories.

“Therefore, I prefer to apply a more fragmented approach to time and the mingling of my characters’ fates and the reality, in order to perform a literary experiment,” she says.

Both Chinese poet Wang Jiaxin and Thomas Girst, BMW Group’s head of cultural engagement, have referred to the novel as a recent example of Bildungsroman, a genre of novel that focuses more on the moral and psychological growth of the main characters.

Speaking about the work, Wang, 62, says: “In essence, M and W’s experiences abroad, and how they seeking to reinvent themselves, emphasize their inner conflicts.”

As for Yang, she says: “Our generation have been living so averagely that we barely got the opportunities to do great things,” adding that her character M, tries harder to pursue the lifestyle of a writer, rather than actually trying to become a real writer.

“Young people today are working hard and striving to achieve an imaginary goal or fantasy scenario, without which they would have no reason to move forward every day. This is a particularly contemporary fable.”

Yang first attempted to write screenplays-one about Shanxi province warlord Yan Xishan (1883-1960) and another centered around vendors selling petty wares in underground passages in Beijing-when she was a sophomore majoring in script writing at the Beijing Film Academy.

While she was simply trying to be ethical and deliver a socially responsible message, she would find that her version of the stories were either subliminally based on something she had previously seen on screen or, in her words, were “compassionate posturing”, because she could not legitimately feel the same hardships as those she was seeking to portray.

“I could only start with things that I’m familiar with,” Yang says.

“It had to be something related to me, but that was not me. I’m not going to write anything that makes others feel I’m projecting sympathy.”

Embedded in the novel is also her disillusionment with the world of art.

Yang studied art history at the University of St Andrews and art business at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London and has built a private collection that includes works by Giovanni Bellini, the Bruegel family and Eugene Delacroix afterward.

Her thesis at St Andrews was about the Duke of Hamilton’s art collection.

In November 2017, 11 woodcuts by German Renaissance figure, Albrecht Durer, collected by Yang, were being exhibited at the German embassy in China.

“It’s my love for art that makes me blame it more,” she says, believing that people these days have overestimated art.

“I’d like to explore the significance that art has played throughout history and the progress of human civilization, and the complexity and contradiction of human nature presented in literature.”

Yang adds that, in some way, literature is her redemption.

“I have to either dissect myself or people around me for my writing. That’s a totally different thing, and I might lose control if I devote too many emotions to it.”

It is not unusual for her to burst into tears, before calming down and returning to her keyboard.

Yang didn’t start writing immediately after returning from abroad in 2016. Instead, she introduced three albums, published by Phaidon, covering the work of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Tiziano Vecellio and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, respectively, and called the Chinese translation of the series, Time Immemorial.

In 2017, she introduced the A to Z of Contemporary Art, a collection of 59 articles published in London-based contemporary art and culture magazine, Frieze.

Influenced by the sound knowledge and academic systems of art in the West, her first reaction was to bring them back home. Yet, she soon realized that such an ambition could not be realized on her own.

She then turned her focus to art and aesthetic education and, last year, Yang published Into Renaissance that is based on her lecture notes from a course for freshmen at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing.

“Finally, I realized I’m not the kind of person with strength in management who is able to control things. I could only step back to something I’m really good at, and that is writing.”

To play her role as a publisher, she wore slim-cut clothes and high heels at the launch of the Chinese translation of the Frieze collection in 2017. Then later, she presented classical and intellectual beauty at the launch of her short Renaissance art history and also at a lecture about Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride at the Netherlands embassy in Beijing in 2018.

At many recent events to promote her novel-which she is currently translating into English-she has preferred casual, neat outfits.

“I feel more and more comfortable these days and am less afraid of showing my antagonistic side.”

Now, one can easily read her through the glint in her eye on the poster for the novel-“I can present my sarcastic side now.”

Click Here: cheap kanken backpack

You May Also Like

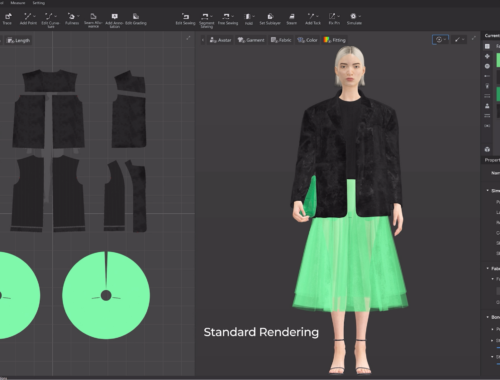

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability

February 28, 2025

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025