The Stop-and-Frisk Approach to Anti-Doping

Can a controversial new form of statistical profiling weed out cheaters?

On July 8, 2016, in the obscure town of Zhirovichi in Belarus, two Iranian hammer throwers had the best day of their lives. Neither had ever come close to the Olympic qualifying standard of 77.0 meters before, but at a track meet on this day they both managed to heave their implements to massive personal-best distances a hair’s breadth beyond the magic line: 77.4 meters for one athlete and 77.18 meters for the other. It was onward to Rio for both of them—where they finished third-last and second-last with throws of 69.15 and 65.03, respectively.

This stroke of incredible (or uncredible) luck is one of the incidents flagged by a new and controversial approach to rooting out dopers and other cheaters in sport. “Performance profiling” is, in a sense, the stop-and-frisk of sports policing, relying on superficial appearances—in this case, an athlete’s sequence of performances—to identify suspicious activity. If a hammer thrower in his thirties records yearly bests of 71.43, 69.88, 71.14, 77.40, and then 69.75 meters, it’s time to start frisking.

The Miracle of Zhirovichi (where, in addition, a Belarusian athlete beat both athletes with a 77.41 that he too has never matched before or since) appears to be a case of “obvious result manipulation,” according to a new journal article on performance profiling, published in Frontiers in Physiology by Sergei Iljukov, of the Research Institute for Olympic Sports in Finland, and Yorck Schumacher, of the Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital in Qatar. When a result seems too good to be true, it might just be one of those magical days—or it might be a rigged measurement, a moved start line, or a telltale sign of doping. Sports officials already watch for these sorts of smoke signals in an informal and ad hoc way to trigger further investigation, but Iljukov and Schumacher argue that it’s time to bring performance profiling into the age of big data and make the process formal, quantifiable, and objective.

Of course, it’s impossible to prove anything with performance profiling, so critics say that it risks tarring innocent athletes with suspicion. Particularly in cycling, attempts to identify maximum possible drug-free power outputs on notable climbs during the Tour de France have been highly controversial. But Iljukov and Schumacher argue that the rise of comprehensive online results databases makes it possible to track athlete progress over the course of many years and identify suspicious jumps. Crucially, identifying such jumps marks the start, not the end, of a more thorough investigation, including initiating targeted surprise testing.

Here’s what four years of performance data looks like for 24 hammer throwers who qualified for the 2016 Rio Olympics. Each year between 2014 and 2017 is represented by a different shape:

The Iranian throwers are numbers 6 and 16. But the researchers also flagged throwers 21 and 24, who notched unusually good performances in 2015 that aren’t backed up by any other performances before or since. These athletes, the authors suggest, would be worth targeting with a few extra unannounced tests.

Beyond identifying individual athletes, performance profiling on a broader scale may also yield insights on how well anti-doping efforts are working and whether new drugs are arriving in circulation. As an illustration, here’s how women’s discus performances evolved after the introduction of anabolic steroids in the 1960s and the subsequent introduction of out-of-competition drug tests in the late 1980s. Black squares are the yearly best performance; white circles are the average of the top 20 performances:

Iljukov and Schumacher also analyzed a decade’s worth of times from the women’s 800 meters at the national championships of a country identified only as “Country X.” (I can deduce which country it is, but have chosen not to identify it to reduce my risk of having my email hacked or being drowned in a butt of vodka.) The depth and quality of performances dip markedly after the introduction in 2009 of the biological passport program, another form of indirect anti-doping in which blood values are monitored over time. Worryingly, however, times have started to get faster again in the past year.

The logic here seems impeccable. Anti-doping officials already do rudimentary targeted testing when they see suspicious patterns, ordering more tests when “particular sudden major improvements in performance” are noted. So making this approach systematic and quantitative would likely catch more cases and lessen the risk of bias in targeting. But logic isn’t the only consideration. When someone is flagged as “suspicious,” it can be very hard to shake off that label, even if there turns out to be a perfectly reasonable explanation for the original anomaly. Of course, the process should be confidential—but that didn’t help the athletes whose biological passports were flagged in preliminary analysis as “likely doping” or “passport suspicious” in data leaked by the Fancy Bears hacking group last summer.

The Zhirovichi hammer throwers highlight another drawback to performance profiling. As seemingly damning as the circumstantial evidence may be, the Iranian throwers took spots at the Olympics, and their performances are still recognized. Unlike the hand-in-a-cookie-jar evidence provided by a positive drug test, the inherently probabilistic nature of performance profiling means you can’t convict anyone—though Iljukov and Schumacher suggest that at least you can flag suspicious meets and officials so you don’t get fooled twice.

The practical difficulties in catching cheaters, whether dopers or otherwise, can sometimes make the whole mission seem hopeless. But to me, the goal shouldn’t be to eradicate doping completely, since that’s virtually impossible. It should be to make it really, really hard to get away with. It’s like shoplifting: We do everything we can to minimize it, but we don’t have existential crises about the pointlessness of anti-theft rules just because it still happens. So, for all its flaws, I hope performance analysis can add another weapon to our anti-doping arsenal. Judging by the results from Country X, we’re going to need it.

Discuss this post on Twitter or Facebook, sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter, and check out my forthcoming book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

You May Also Like

Dino Game: A Timeless Classic in the World of Online Gaming

March 22, 2025

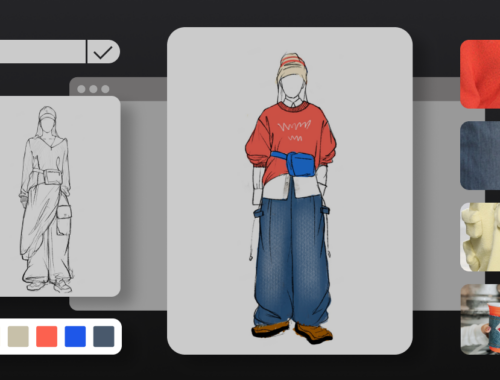

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025