The Science of Why We Fall on Mountain Trails

It’s called accidentology. Yes, that’s a real word.

It’s understandable that the headlines we see about death in the Alps tend to focus on climbers plunging off glaciers or cows goring hikers. These are, of course, real dangers, which is why Austrian authorities have produced a safety guide warning visiting hikers to avoid making direct eye contact with cows. (“Only in an absolute emergency,” the guide adds, “should a well-placed blow be delivered to the cow’s nose.”)

But most of the emergency calls that flood into the Austrian Alpine Police each summer are far more mundane. Someone is hiking, generally on a well-used trail, and they fall and hurt themselves. Between 2006 and 2014, according to a recent study in BMJ Open Sport and Exercise Medicine by researchers at the University of Innsbruck, Austrian police fielded 5,368 such calls from hikers. That doesn’t include climbers, skiers, wingsuit flyers, or any other activity that you couldn’t comfortably do in lederhosen. It also doesn’t include heart attacks or avalanches—just falls. Of those falls, 331 were fatal.

The apparent perils of hiking are mostly a numbers game, of course. The estimate quoted in the Austrian study is that about 40 million people a year visit altitudes above 6,500 feet in the Alps each year. Most of them are there to hike, some with very little experience and poor physical conditioning. The sheer numbers mean that even though hiking is comparatively safe, the number of low-probability accidents adds up.

For example, a study of mountain accidents in France last year found that only 4 percent of on-trail hiking accidents where mountain rescue is called result in death. In comparison, 15 percent of off-trail hiking calls, 20 percent of snow mountaineering calls, 35 percent of whitewater calls, and 47 percent of BASE-jumping calls involve a fatality. But because of the differences in participation, hiking is actually the leading overall cause of sport-related deaths in Switzerland, accounting for 25 percent of the total, compared to 17 percent for mountaineering, 8 percent for ski touring, 2.7 percent for rock climbing, and just 1.8 percent for BASE jumping.

All of which is to say that it’s worth taking a moment to parse the breakdown of all those calls to the Austrian Alpine Police. Who called? When? Why? Here are a few patterns they noted:

- Downhills are riskier. Just over 75 percent of the falls occurred during descents, compared to 20 percent on ascents and 5 percent on level ground. Several factors probably contribute to this: You’re going faster on the downhill, you’re pounding your quads with unfamiliar eccentric muscle contractions, you may have had a beer at the summit lodge, and you’re already fatigued from the ascent. (On that note, it would be interesting to find comparable data from, say, Grand Canyon, where the descent precedes the ascent.) This isn’t a big surprise, but it’s worth reminding yourself.

- External conditions aren’t a big factor. The accidents we’re talking about here mostly weren’t the cliché of the foolish hiker wandering off the trail at dusk in a thick fog or heavy rainstorm. In fact, 90 percent of accidents took place during good weather, with no precipitation, fog, or darkness. Moreover, 81 percent of the accidents took place on marked trails or paths, though those paths were passing through rocky terrain in 61 percent of the cases. For the most part, the hikers were doing what they were supposed to do when they fell.

- Men are idiots. Okay, that’s a little harsh. In fact, women accounted for more than half the accidents overall—but they were less likely to have serious ones. Women had 55 percent of the nonfatal accidents, but just 28 percent of the fatal ones. Possibly related: Men were significantly more likely to have an off-trail hiking accident than women.

Since we don’t know the gender breakdown of the total population of people who were hiking in the Austrian Alps, we can’t make exact calculations of the probability that a given woman or man will have an accident. On the basis of a previous survey-based study, the researchers assume that there’s a roughly 60-40 split, with men outnumbering women. On that basis, the new injury data suggests that women are almost twice as likely to call in to report a nonfatal accident but only half as likely to suffer a fatal accident.

That finding jibes with other data on risky behavior in the wilderness. In another recent study, observers staked out two high-risk areas along the Merced River in Yosemite—near a footbridge and above a waterfall—where more than ten people have drowned over the past decade. Over the course of 32 days of observation, they saw 1,417 people enter the high-risk areas, which in some cases meant hopping over or going around a fence. The most common offenders: “males, teens, and people who were alone.” Since they also observed how many men and women didn’t enter the high-risk areas, they were able to calculate that men were more than twice as likely as women to take the risk.

What’s the moral of all this? Many of the findings are pretty much what you’d expect, but it’s always useful to check your assumptions against the actual data. The main surprise was the predominance of accidents in good weather and good light on marked trails. Your spidey sense tells you to slow down and watch your step when you sense danger. The trick, I guess, is to stay alert even when you don’t.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.

You May Also Like

ユニットハウスのメリットとデメリットを徹底解説

March 22, 2025

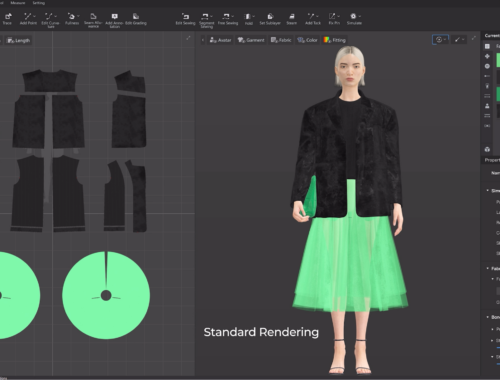

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025