The New Science of Training Your Gut

Testing the idea that you can improve your ability to eat on the run

There is both an art and a science to the pursuit of sporting excellence, and it’s not uncommon for devotees of the former to argue that egghead scientists simply don’t understand how races are run in the real world. One of the places where this chasm yawns particularly wide is race nutrition. Science says that endurance athletes can and should ingest up to 90 grams of carbohydrates—three to four gels—per hour for exercise lasting three or more hours. The harsh and flatulent reality, according to field studies, is that marathoners and ultramarathoners typically manage to choke down barely a third of that goal.

The main reason is pretty simple. If you wake up one morning and decide to try downing 90 grams of carbs per hour on your run, you have an extremely good chance of developing what the eggheads call “exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome.” The longer you exercise, the more likely you are to run into trouble: 73 percent of 24-hour ultramarathoners report “severe” GI symptoms, as do 85 percent of multistage ultrarunners.

What exactly does this syndrome entail? Well, if you insist, it may involve:

[G]ut discomfort, upper-gastrointestinal symptoms (gastrooesophageal and gastro-duodenal originated: projectile vomiting, regurgitation, urge to regurgitate, gastric bloating, belching, stomach pain, and heartburn/gastric acidosis), lower-gastrointestinal symptoms (intestinal originated: flatulence including lower-abdominal bloating, urge to defecate, abdominal pain, abnormal defecation including loose water stools, diarrhoea and blood in stools), and other related symptoms (nausea, dizziness, and stitch).

The standard advice for surmounting this problem is, as sports nutrition research Asker Jeukendrup put it in a Sports Medicine review paper last year, to “train your gut.” If 30 grams of carbohydrates per hour is all your stomach can tolerate right now, then start by trying 35 grams in training for a while. Eventually, according to theory and anecdotal report, you’ll learn to tolerate higher levels, thanks to a variety of adaptations like decreased perception of fullness and increased activation of the transporters that move carbohydrates from your gut into your bloodstream.

As logical as this sounds, there hasn’t been much evidence to demonstrate that it really works. That’s why a paper in this month’s Scandinavian Journal of Science and Medicine in Sports from a group at Monash University in Australia is particularly interesting. The researchers tried a two-week “repetitive gut challenge” to train the gut, and as predicted, they found improved absorption of carbohydrates and improved running performance.

The study involved 18 trained runners who had to complete a test scenario that involved two hours of steady running while consuming 90 grams of carbohydrates (in a two-to-one glucose-to-fructose ratio) per hour followed immediately by a one-hour time trial. Sure enough, this protocol wreaked havoc on their guts: 100 percent of the subjects experienced at least “moderate” GI symptoms and 67 percent experienced “severe” symptoms. In addition, 61 percent of the runners had signs of carbohydrate malabsorption, as indicated by the hydrogen content of their breath. In addition to exacerbating GI discomfort, that malabsorption means some of the fuel wasn’t getting to the muscles where it was needed.

The next stage was two weeks of gut training, which included ten days of one-hour runs. Some of the participants took in 90 grams of carbohydrates in gel form during those runs, just as in the initial gut-challenge test. The others received placebo gels matched for taste and texture but containing no carbohydrates.

Then they repeated the initial gut challenge (two hours of steady running followed by a one-hour time trial). The gut training wasn’t a panacea: Most participants still reported GI symptoms. But overall, the carbohydrate training group reported a 44 percent reduction in gut discomfort and a 60 percent reduction in total GI symptoms. They also had less carbohydrate malabsorption than the placebo group. And, perhaps most important, they improved their time trial performance from 11.7 to 12.3 kilometers, while the placebo group didn’t improve.

Here’s what the average gut discomfort ratings, on a scale of zero to ten, looked like for the carbohydrate training group during their three-hour gut-challenge test. The black squares are before the two-week training period, and the white squares are after:

Gut training isn’t the only tactic to consider. Ricardo Costa, the senior author of the study, has written a guide to managing GI symptoms in ultra-endurance sports, which is available on the Ultra Sports Science Foundation’s website. There’s not much evidence for supplements and probiotics, Costa concludes. Hydration is important, and temporarily avoiding “FODMAPs,” a class of poorly digested carbohydrates that includes wheat, milk, onions, stone fruit, and many legumes, in the days leading up to a race may be useful.

But the bottom line is that deliberately and systematically preparing your digestive system for the demands you intend to put on it while racing is probably a good idea, particularly for marathon or ultramarathon races. The gut, as an influential journal article in 1993 suggested, is an “athletic organ.” Just like your muscles, it needs training to perform at its best.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, is now available! For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.

You May Also Like

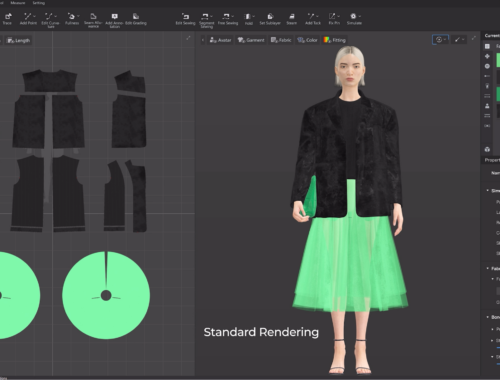

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

March 1, 2025