The Miraculous True Story of the Dog Who Lived

It was just another beautiful day in the mountains for the author and his one-year-old Australian shepherd, Merle, when their lives changed in an instant

We charged up the final ascent of 13,041-foot Grand Traverse Peak, about seven miles east of Vail, Colorado. My new running partner, Merle Hamburger—a one-year-old blue Australian shepherd so nicknamed because my four-year-old son, Axel, couldn’t pronounce the dog's given last name, Haggard—seemed unfazed by the previous eight miles we’d covered. I also felt strong, energized by the clear Rocky Mountain air and endless blue sky. It was Father’s Day 2017, and I was set to return home to Axel, my nine-year-old daughter, Lily, and my wife, Susan, by noon. Merle and I had cruised up meandering, buff singletrack and firm, sun-cupped snow above treeline, and now, ahead of schedule, we could take our time on the exposed alpine ridge, taking in the views of the neighboring 13ers—Mount Valhalla, Snow Peak, and the mountains of the rugged Gore Range.

As I reached the summit, I heard a short yelp but assumed Merle would be seconds behind me, as he had been all morning. I snapped a panorama of the view for my family, called out to the dog, then tucked my phone in my pack and headed back down the trail. Merle was nowhere to be seen. “Merle! Merle!” I called. “Where are you?” I felt a tickle of panic in my throat as I threaded my way down the ridge, still seeing no signs of him. But he was strong and young and athletic and invincible. He must be fine, I reasoned.

Then, several hundred feet farther down, I saw his paw prints on a five-foot-wide strip of snow at the top of a steep couloir on the north side of the ridge. I cautiously followed them to the edge until they disappeared entirely in the hard, steep chute. About 800 feet below, the couloir ended abruptly in a boulder field and a massive cliff. Below that, I could see a wide, empty, snow-covered basin. There was no sign of Merle in the rock field or the bowl. I could still hear that last yelp in my mind, and now I realized what it had signaled.

Merle was gone.

Merle and I had started the day at 4 a.m. at our home in Eagle, Colorado, where I work as a freelance model and actor. I’d stacked my running clothes next to the bed the night before and filled my pack with water bottles, trail food, and a can of sardines—my go-to for big days in the mountains. It would be my first big run in the Gore Range this summer and my first big adventure with Merle.

We’d bought the 40-pound blue-and-brown-eyed blue merle Aussie six months earlier from a breeder in Durango. Merle quickly proved himself to be a phenomenal running partner, and I marveled at the efficiency of his gait, cadence, and indefatigable attitude. On our backyard trails, he always ran at my heels, offering reassurance in an area where mountain lions are common and known to attack from behind. Merle could bang out 15 miles easy.

That morning, we drove 36 miles from our house to the Deluge Lake trailhead in East Vail. I’d grown up in Illinois, but as a kid made frequent trips to Vail, where my late father had a house. I’d hiked this trail every year since I was seven, and it had always been a special place for my dad, a mountaineer and ultrarunner. He’d take me and my younger sister, Celenda, up the eight miles to Deluge lake—training, he called it, for our annual summit of Mount of the Holy Cross, the peak where I would spread his ashes in 2002, after he died from complications associated with his cancer.

Merle and I set off, and by 7 a.m., we’d reached the Swedish Grave, a historic site four miles into the route. The sun had yet to reach us, and I took a favorite alternate path that ascended steeply to tree line, then skirted an alpine cirque on its way toward Deluge Lake and Grand Traverse Peak, a pyramid-shaped mountain flanked by three major drainages. The still-firm snow provided excellent footing, except along the rotten edges at the occasional talus outcroppings. We climbed steadily uphill, contouring the basin. When we reached the base of the peak and began the tedious scree ascent, Merle struggled a few times, but I let him navigate on his own and return to my heel.

I hadn’t thought twice about taking Merle up Grand Traverse; in fact, I expected him to beat me to the summit. Which is why when, even as I stood above the steep couloir, I still thought, “It’s going to be OK.” I knew the summit was the only spot on the trail where I got cell service, so I called Susan, panicked. “Merle fell! I don’t know what the fuck happened,” I shouted. “I’m going for him. It’s OK. I’m OK.”

Then I saw something running in the basin below me. “Holy shit, there he is! Oh my god! I’m OK. I need to go.” “OK, be safe,” was all Susan had time to say before I hung up and ran down the ridge. Merle was sprinting downhill, away from me. I couldn’t follow Merle’s nearly vertical route without technical climbing gear, so I needed to find a safer way into the basin. The next couloir had a massive cornice hanging ominously above it. I debated whether to try my luck, but I knew if the ice fell, I’d be dragged through a cheese grater of rock. The next gully looked better—fourth-class climbing down wet lichen. I downclimbed several hundred feet before it cliffed out. “God fucking dammit,” I thought. As I climbed back up, I resolved not to die that day. My kids don’t deserve this, I thought.

Several hundred feet farther down the ridge, I found a steep, off-camber couloir filled with rotten snow. Not ideal, but workable. I turned around and carefully started descending backward. With each step, I punched my fists wrist-deep into the snow and kicked my feet to form steps till my toes started to bleed. A fall would send me tomahawking down 150 vertical feet to the rock and ice below. As soon as the pitch allowed, I turned and glissaded precariously through the apron and into the basin. The wrong basin, I realized too late. Merle had fallen into the basin to the west. I continued down the snowfield and out to where I’d meet Merle if he had continued to descend. There was no sign of him. I started to run up the snow-covered bowl toward where I’d last seen him. I felt like my head was going to explode and my lungs burned, but all I could think was, “Get the hell up there.”

After 30 minutes of hiking up the bowl, I saw Merle standing on a large rock outcropping. Relief washed over me. “Merle, come here, buddy. Good dog. I’m so sorry,” I called. But he ran away. I didn’t blame him. I’d taken him on a selfish pursuit to a selfish place. I’d pushed him too far.

I followed Merle up the basin. Soon, I was close enough to see that he looked oddly swollen, covered with lacerations, and his gait was hobbled and stiff. When I got to within a few feet of him, he dove into a crack at the edge of a talus field. I grabbed his back legs for a moment, but he squirmed away from me, deep into a subterranean pocket within the boulders. I started throwing rocks and moving snow away from the crack’s entrance, until two backyard-grill-size boulders slid together, clamping my ring finger between them. I yanked out my hand and saw the nail was smashed and spurting blood. I threw on a glove from my pack to contain the flow, then kept digging. A few minutes later, I’d cleared enough snow to stick my head down the crack, but it was too narrow for me to wiggle my shoulders through. I peered down into the darkness. I could hear the jingle of Merle’s collar, but I couldn’t see him.

I yelled, alternating between angry and nearly hysterical to calm and coaxing. No response. I decided to give him space. Maybe he was OK and my panic was freaking him out. I opened the can of sardines and left them as a lure at the mouth of the cave. While I waited, I went to the scene of the fall. Above, I saw the path Merle had taken: He’d slid on the upper snowfield, fallen off a 40-foot cliff, then rolled down another 100-foot cliff to the lower snowfield where we now stood. How did he walk away from this? I thought.

I returned to the crack, leaned in, and screamed his name again. Inside, it smelled wet. After a decade of archery hunting, I knew the smell—it was as if an elk had been field dressed and the organs and bodily fluid were leaking on the ground. It smelled like death. I spent another hour crouched outside the cave, until the jingle of the collar and Merle’s deep breathing stopped.

It was late afternoon, and I worried about losing daylight. I was on the wrong side of a big mountain, many miles from home, and not prepared to spend the night outside. I packed up, traversed the basin, descended a rotten snowfield, then found my way to the base of the couloir I’d come down. I climbed the melting snowpack as quickly as I could, reusing my kicked steps from the descent. When I reached the saddle, I phoned Susan.

“I’m okay, Sus, but I’m walking down alone.”

“Is he dead?”

“Yeah.”

Then I ran away, back down the trail. I didn’t know that Lily and Axel had heard me through our car’s Bluetooth system. After I hung up, they burst into tears.

I’ve always owned a dog. Each accompanied me into the mountains, where, bounding off-leash, they seemed protected by an invincible athleticism. Merle, more than any of the others, was bred for the trail. I had assumed the rugged Aussie would take to the high alpine intuitively. But the reality is that almost no one thinks about training their dogs for the mountains.

In potentially deadly terrain, it’s critical that humans help dogs understand their limits, says Amber Quann, who runs Summit Dog Training in Fort Collins. She helps owners and dogs prepare for outdoor adventures through relationship building and body conditioning classes. “My dog will push himself to his limits all the time. One day, we were playing ball in the snow for 45 minutes, and while he showed no signs of slowing down, I noticed one stutter step before he resumed his normal stride. I flipped him over, then noticed his paw was cut.”

Dogs can’t talk to us, but they have other ways of communicating that we need to pay attention to. It’s up to us to learn our pet’s idiosyncrasies. Of course, it’s difficult to tune into a dog’s subtle behavior changes when you’re listening to a podcast or chatting with your climbing partner. “It’s as simple as putting your phone down and being present in the moment,” Quann says.

That communication leads to trust, which is the other part of taking a dog into the mountains. “You have to trust your dog to make good decisions by giving her a safe amount of freedom and not always interrupting her natural behaviors,” Quann says. “We want owners to help their dogs but not micromanage them.” The bottom line, she says, is if an outing will be more stressful with your dog, leave her at home. “You need to be OK putting the dog’s best interest first.”

I knew Susan questioned whether I’d done enough to keep Merle safe. My possible carelessness gnawed at me, too, so I called our longtime vet and friend, Charlie Meynier, owner of Vail Valley Animal Hospital, to try to get some closure. He assured me I did everything I could to save Merle. “He crawled into that cave to secure shelter, which is typical behavior for a dog in distress who is on the verge of dying—they hide and hunker down,” he said. “His body and brain went into survival mode.”

Three weeks later, on July 8, local real estate agent Dana Dennis Gumber was preparing a listing in East Vail, near the Deluge Lake trailhead, when she noticed a ragged-looking dog hanging near the property’s deck. She assumed the animal belonged to the landscapers working on the complex, but when she returned to the house two hours later, the crew had left and the dog was curled up by the front door. Gumber had noticed him limping earlier, and now, as she approached, she saw that he was filthy, weak, and skeletally thin. She ushered the dog into her car, then brought him to her Eagle Vail home for food and water.

Miraculously, Gumber found that the dog still had a collar. That afternoon, she left a voicemail on my cell: “I have Merle. Please call me.”

I’d left town a few days earlier for a work trip to Austria to model in a commercial for a river cruise company. I got the call as cameras were rolling and immediately Facetimed Susan back home, where it wasn’t yet dawn. Neither of us knew what the message meant. Susan assumed it was some kind of sick prank, but she agreed to call the woman back that morning. A few hours later, we had an answer: Merle was alive, Susan said. “I’m getting him this afternoon.” When she got to Gumber’s house, she collapsed to the floor as soon as she saw Merle, gently stroking his battered body. He seemed to recognize her, though his wandering eyes made her think he’d suffered some kind of brain damage.

Susan immediately drove him to the Vail Valley Animal Hospital, where emergency veterinarian Rebecca Hall found that Merle had two detached retinas, a punctured lung, facial lacerations, sores on his hind legs, and had lost about 12 pounds—almost a third of his body weight. His stool showed that he’d survived on pine needles and berries. He was tattered, but remarkably, he didn’t need stitches and none of his bones were broken. Hall was amazed. “House pets don’t always have the smarts to survive in the wild, but Merle has some herding breed in him,” she said. “He’s certainly intelligent, has some survival instincts, and had a strong will to live.”

Merle had fallen more than 140 vertical feet. He had hunkered down in a cave, likely gone into a coma, then woken up and, seriously injured, covered 20 miles in 20 days to return home. “You don’t hear a lot of stories about dogs surviving in the wilderness,” Quann says. “But herding breeds are very driven and tough. They possess extra motivation. His return was most likely testament to his positive association with home. These dogs are incredibly bonded to their owners.”

Quann says Merle likely followed well-established human smells on the trail to get back to civilization. Humans are decidedly limited in the olfactory and auditory departments, so we’ll never truly grasp how strong those senses are in a dog. “We can’t wrap our brains around how easy it is for a dog to follow a scent using such a small amount of odor or to hear traffic miles away,” Quann says. Plus, after a week in the wilderness, Merle’s senses most likely sharpened. “I’d guess it was this combination, plus intuition and just some good luck, that got him home,” she says.

Over the next week, while I was still away, Merle recovered beautifully. His wandering eyes straightened, he gained weight, and his gait returned to normal. Axel and Lily, who now fully believe in miracles, spent every moment with their best friend. When I got home just after midnight later that month, I walked through the front door, anxious to see Merle. Would he run from me again? I entered our living room, then kneeled down and called him to me. He gave a quick bark before lowering his ears, tucking in his tail, and wiggling onto my lap. He clawed my chest like he wanted to climb on top of my shoulders and kissed my face.

You May Also Like

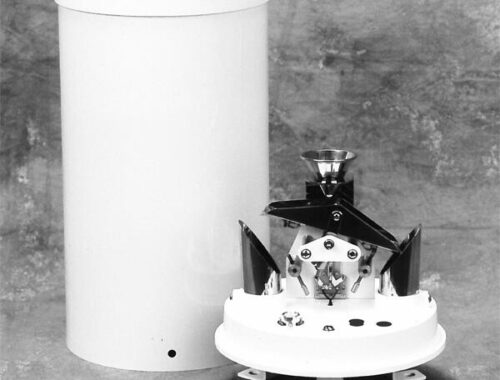

ユニットハウスのメリットとデメリットを徹底解説

March 21, 2025

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025