The Man Who Survived a Rattler, Bear, and Shark Attack

>

Dylan McWilliams might be the luckiest guy in the world. He might also be the unluckiest guy in the world. That depends on whether you think surviving a rattlesnake bite, a bear attack, and a shark bite within three years is fortunate or if he must have created some seriously bad juju to be bitten by all those animals in the first place.

For the past few years, McWilliams, originally from Colorado Springs, Colorado, has been backpacking around the United States and Canada, making money on odd jobs and as an outdoors survival instructor. That’s partly how he came to be attacked by three dangerous animals, all before he was old enough to legally sip a beer. Below, McWilliams tells the story of each attack—any one of which could have killed him.

In September 2015, I was hiking out of Grandstaff Canyon, near Moab, Utah, at about 7:45 p.m., after an all-day high-angle wilderness rescue training. The sun was setting. I had just switched from my climbing shoes to sandals and rolled up my pants to cool off. My three buddies and I were a few miles from the trailhead.

I was second in line, and as I stepped off a ledge, I felt a sharp, needle-like stab in my right leg. I thought I kicked a cactus. I looked down to see two puncture wounds an inch apart in my shin. Sure enough, a pygmy rattlesnake, dark, reddish-brown with pink spots, lay coiled up under the ledge.

Thanks to my wilderness emergency medical response training, I knew I had two options. I could call a helicopter to airlift me to the hospital, or I could wait it out in hopes that it was a dry bite (no injected venom). Knowing roughly 50 percent of rattlesnake hits are dry, I decided to take my chances.

I sat down on the red slickrock and waited. I pounded water and kept my heart rate down to dilute and slow the spread of any venom. We watched, ready to call a chopper at the first sign of swelling or nausea. After 20 minutes, when none came, we decided to hike out. It took us three hours to cover three miles. Downhill. I vomited once that night and once the next morning, but after that I was fine and grateful that my gamble paid off.

Then, last July, I was teaching wilderness survival skills at Glacier View Ranch near Boulder, Colorado, and five of my co-workers invited me to sleep outside with them. We spread out our sleeping bags and dozed off.

Around 4 a.m., I woke up to a crunch—like someone squeezing a handful of chips—and felt a jerk from the base of my skull. A 300-pound male black bear had dug his claws into my scalp. He dragged my six-foot, 180-pound body by the head 12 feet from my bag. I punched the bear hard and jabbed his eyeballs. He was pissed, and he dropped me and stomped on my chest a few times before running away.

The whole thing lasted less than 25 seconds.

I grabbed my head and blood gushed down my arms. It soaked my flannel shirt and my jeans, dripped on to my bare feet, and ran into my eyes. I couldn’t see. I am going blind, I thought.

That was the scariest part. I knew it was bad.

Someone called Boulder County EMS, and an ambulance took me to a hospital, where doctors told me I had five bite marks in my head, deep cuts from claws across my face, and bruises on my chest and neck. Colorado Parks and Wildlife caught and caged the bear. They tested him, found my blood and bits of scalp under his claws, and put him down.

The attack puzzled me. We knew better than to leave food out. We were in the middle of an established campground, and there were dozens of kids in cabins 100 feet away. The shock was nerve-wracking, but I camped again two days later and haven’t looked back.

Then, this April, I was attacked by a tiger shark while surfing off the coast of Shipwreck Beach in Keoniloa Bay, on the south shore of Kauai, Hawaii. It was day five of my two-week trip, and I had just finished helping emergency response teams with flood rescue and mitigation on the North Shore. I was ready for a break and eager to get on my board. I went out at 7:15 a.m.—just three other surfers in the water and incredible waves. I caught one, rode it in, and turned around to paddle out again.

About 30 yards offshore, I felt a hard bump and sharp twinge on the inside of my left calf. For a split second, I was confused, then saw my body and red board shorts marinating in a cloud of blood. Shark, I thought.

I kicked out and connected with its nose. It felt like hitting a giant rubber inner tube underwater, in slow motion. Then I saw it: a huge six-foot silhouette circling below my board. I spun around and paddled swiftly toward shore, praying I still had my leg. Time stopped. All I could think about was getting to land. It took an eternity.

I crawled onto the sand. Blood pumped out of holes in my leg. A local lady saw it happen and called an ambulance. I got seven stitches, loosely sewn so the wound wouldn’t become infected. Three days later, determined not to miss this opportunity, I duct-taped my leg and surfed the same beach. My trip clock was ticking, and I figured if I didn’t get back on my board, I never would.

I don’t think I’d call it lucky or unlucky. Stuff happens. I was just in the wrong places at the wrong times. I’ve revered Davy Crockett since childhood—experiencing outdoor adventures and honing my survival skills are a huge part of me. Now I travel the United States giving wilderness seminars to people who want to learn how to thrive outside.

Statistically, I might be the luckiest man in the world, but even so, these fluke attacks won’t keep me from doing what I love most: being outdoors. And being able to do what I love? That, to me, is lucky.

You May Also Like

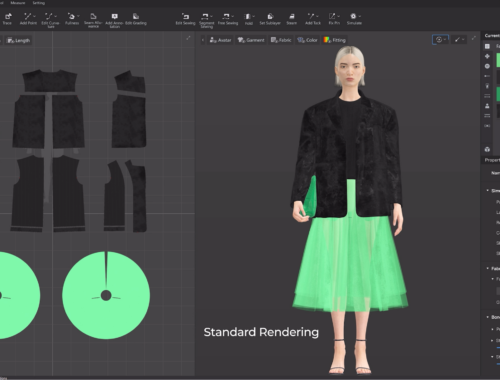

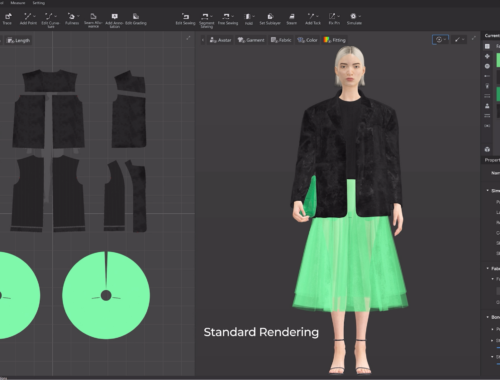

AI in Fashion: Redefining Design, Retail, and Sustainability for the Future

February 28, 2025

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025