The Last Words of Alpinist Jeff Lowe

>

Legendary climber Jeff Lowe, who died on August 24 at the age of 67, took more risks than most. At 7 years old, he climbed the Grand Teton. At 27, he soloed Telluride’s 400-foot Bridal Veil Falls. Perhaps his most famous and dangerous ascent was his 1991 solo climb of the north face of the Eiger.

In June, a friend who was close with Lowe told me that Lowe was in his final days and had stories he wanted to share. I was eager to meet him. I’m a rather conservative endurance runner, not a daring climber. But I am fascinated by a mind like Lowe’s that takes a body to places many wouldn’t dare go.

For the past two decades an unknown neurodegenerative disorder, whose symptoms resemble ALS, had stolen away most of his physical capabilities, including his speech. He was physically bound to a wheelchair; sometimes he needed supplemental oxygen. A tracheostomy tube expelled mucus from his lungs. Lowe would occasionally wake up and momentarily forget he was trapped in a stationary body that was quickly breaking down. His mind, however, was still whip sharp.

On my way to meet Lowe in Boulder, Colorado, that summer afternoon, I accidentally texted him a message intended for someone else.

“Oops!! Wrong person! On my way,” I attempted to explain my mistake.

“I’m not always wrong,” he wrote back. “Sometimes I’m even the right person at the right time.”

Jeff met me outside his nursing home. He was sitting in his motorized chair and smiling out at me from under his Indiana Jones-esque hat. As I asked questions, he slowly pecked out his answers one letter at a time on an I-Pad with his stylus pen. Occasionally he paused to summon what little strength he had left to cough out the mucus that had accumulated in his lungs. At one point he motioned to me to make sure his trache was draining into the bag on his chest.

We live in an age where more unskilled climbers appear to be taking impatient risks all for the sake of a social media boost. Lowe’s view of risk hadn’t changed, he said. “I have always felt that no climb is worth losing the tip of a little toe. A parallel thought is that if I had died during a climb, it would put an asterisk on all my climbs. Being willing to risk it all for any given climb will inevitably end at some point in disaster.”

“I mean any fool can hurl themselves at a climb that is beyond their abilities to safely negotiate. You may get away with such an approach nine times, but the tenth time you don’t come back. That includes what climbers call objective risks such as avalanches and rock fall. Many climbers use the term ‘objective hazard; to denote something they aren’t to be held accountable for. I held myself accountable for the mistakes I made over the years.”

Toward the end of our hour-long meeting, he began relaying the story of his last big Himalayan climb, in 1993. But it was time for me to go; I had plans. “I’ll email the rest to you later,” Jeff typed. “I’ll be back,” I reassured him. He never did email me. I didn’t get the chance to go back. It was his final interview with a journalist.

Like many people with diseases similar to ALS, Jeff was afraid of drowning in his own fluid, a term described by doctors as having air hunger. An ironic fear, perhaps, for an alpinist who spent his life climbing towards thinner air.

Seven weeks after our interview, death came for the alpinist and Lowe passed away. He was at a new care facility in Fort Collins with his cousin George Lowe, daughter Sonja, climbing friend Michael Weis, and close friend and former caregiver Chris Wolfman. They were all outside, at a spot they affectionately called “basecamp.”

You May Also Like

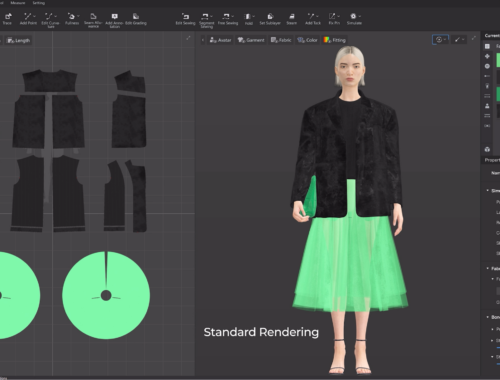

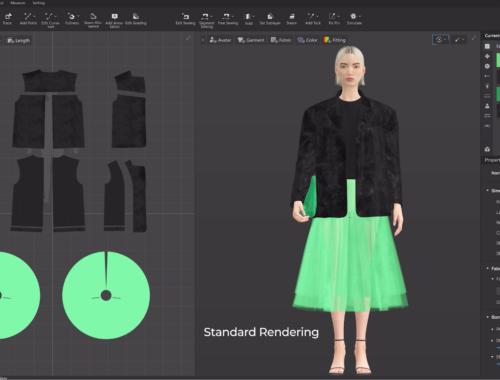

AI in Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining Design, Production, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025

**AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability**

February 28, 2025