The Grand Canyon Speed Record Has Fallen. Again.

>

Five days after Swedish runner Ida Nilsson ran a fastest known time (FKT) for the Grand Canyon rim-to-rim-to-rim (R2R2R), a new record has already taken its place. On November 21, Taylor Nowlin shaved three minutes off Nilsson’s time, completing the south-north-south double crossing in 7 hours, 25 minutes, 58 seconds.

Even if you’re an ultrarunning fan, you’ve likely never heard Nowlin’s name before, because the unsponsored 26-year-old is a relative newcomer to competitive trail running. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Nowlin was a steeplechaser at the Oregon State University (“I was good,” she says, “but never a huge standout.”) before moving to Crested Butte, Colorado, in 2014, where she met mountain-running pro Stevie Kremer, who encouraged her to start running trails. A few years of casual racing evolved into more disciplined training this year.

And it’s clearly paid off. In the past ten months, she’s made quick work of notching podium finishes at major races like the Lake Sonoma 50-miler and the Speedgoat 50K.

Earlier this month, Nowlin was gearing up for the North Face Endurance Challenge Championships 50-miler, which was scheduled to take place in mid-November. When California wildfires led to the race’s last-minute cancellation, she found herself with pent-up fitness to burn. The Grand Canyon double crossing—roughly 42 miles with 20,000 feet of total elevation change, and located just a 90-minute drive from her home in Flagstaff, Arizona—was the perfect outlet.

If this all sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the very same situation that led Nilsson to take a swing at the record days before Nowlin’s attempt. And two days after Nilsson set the record, pro runner Sandi Nypaver (who also trained for TNF 50) put down a time just three minutes shy of Nilsson’s and 20 minutes under Cat Bradley’s 2017 record. This was the most activity the canyon had seen from fast women since 2011, when the last record before Bradley’s was set by ultrarunner Bethany Lewis.

Nowlin wasn’t deterred by the company. “FKTs are a really cool way to compete against other people who you may not have had the chance to toe the line with in a traditional race,” she says. “This was an opportunity for me to measure myself against some incredible names in ultrarunning that I’ve never raced against.” The day before her attempt, Nowlin researched Nilsson’s and Nypaver’s split times online. Nico Barraza, her coach and boyfriend, enlisted a couple of local friends to crew at the North Rim. Then it was go time.

The morning of November 21 was cold and overcast, with temperatures hovering around freezing. Nowlin took off from the South Rim just after 6 A.M. at a pace that she hoped would put her back at the South Rim in seven hours.

The cold turned out to be the biggest obstacle that Nowlin faced all day. “It’s hard to move quickly and get to things in your pack when it’s freezing and you’re in split shorts,” she says. To make matters worse, Nowlin suffers blurry vision in cold weather. Halfway down the descent from the North Rim, her sight grew fuzzy. Within a few miles, she couldn’t read the numbers on her watch.

Unable to check her time—and convinced she was behind record pace—she committed to simply running the final 15 miles as fast as she could. But mixed in with the panic was a sense of relief: freed from the stress of splits and pace goals, Nowlin says she “just accepted that if it was going to happen, it would happen.”

When she topped out the South Rim, she had no idea whether she had set the record. A friend had to read her the time on her watch. When she knew the FKT was hers, relief and excitement weren’t the first emotions she experienced. “I think I felt how most people do after running 42 miles,” she says. “Hungry for popsicles and desperate for a shower.”

Looking back, Nowlin says she thinks her attempt was far from perfect. But from the outset, it was about more than speed. “Women in trail running have incredible momentum right now,” she says. “There’s a culture of encouraging one another to go hard on race day or go after FKTs. Challenging the R2R2R FKT was my way of contributing to that momentum.” Nowlin says she hopes her record will inspire other women to put down even faster times.

On a great day, with the right combination of fitness, technical skill, and luck, she thinks it’s possible for the women’s canyon record to go under seven hours. “If the men’s record is in the five-hour range,” she says. “I see no reason why the women’s record can’t be in the six-hour range.” With so many women chasing after the mark, that may not be too far off.

You May Also Like

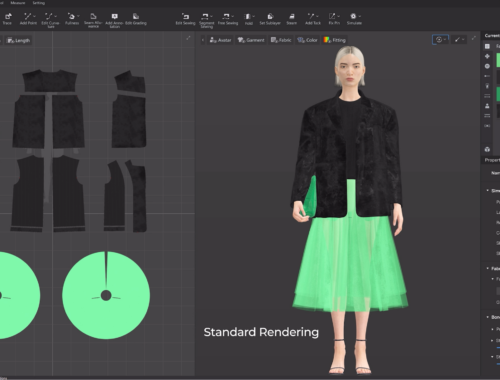

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Supply Chains

February 28, 2025

Generated Blog Post Title

February 28, 2025