The First Thru-Hike of the Mexican Border

After six months and 2,000 miles of hiking, Tenny Ostrem and Claire Wernstedt-Lynch finally reached the Gulf of Mexico

“It’s really dangerous where you’re headed,” said the driver, glancing into the rearview mirror, his brow furrowed in concern. “People die out there.”

In the back seat, Tenny Ostrem and Claire Wernstedt-Lynch felt their spirits sink. The two 27-year-old backpackers were ten days into their attempt to become the first people to thru-hike the length of the U.S.-Mexico border, and they’d been having similar conversations with concerned friends and family for months. Nearly everyone who heard about their plans to walk 1,954 miles from San Diego, California, to the Gulf of Mexico told them the remote sections of the border were simply too dangerous to visit. Especially on foot. Especially for two women.

As they planned the trip, however, Ostrem and Wernstedt-Lynch noticed a pattern. People who lived in the borderlands—the activists, ranchers, and Rio Grande guides they contacted while mapping out their route—tended to be more encouraging than those who lived in the hikers’ respective home states of Kentucky and Maryland. So, on November 19, 2017, after a year of preparation, the two friends finally flew to San Diego and took their first tentative steps eastward from the Pacific.

When the hikers reached the outskirts of Calexico ten days later, they were on edge and exhausted. The night before, they heard footsteps outside their tent. A Border Patrol agent pursued them on foot into California’s 31,357-acre Jacumba Wilderness and referenced the “high-activity areas” ahead. Each day, they saw artifacts left by migrants—T-shirts, water bottles, backpacks. So when the ride-share driver who was taking them to a hotel in Calexico for the night jumped into a lecture on the dangers of hiking in the desert, they braced themselves for gruesome tales of armed drug-running kidnappers.

“There’s no water out there,” the driver concluded instead as they neared their destination. “It’s hot, and there are rattlesnakes—not to mention the cougars, you know, mountain lions.”

That night, the hikers couldn’t stop laughing. They had each logged more than 4,000 miles on trails, often in black bear and cougar country; wildlife was the least of their concerns. That conversation soon became a microcosm for their entire hike. Americans of all political leanings seemed to view the border as a kind of war zone, and the hikers constantly had to square their preconceptions and fears with what they discovered on the ground. Repeatedly throughout the trip, they would hear that the really dangerous area started 50 miles ahead. When they reached that section, the locals there would say the same thing.

Ostrem and Wernstedt-Lynch met while thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail in 2013. They had started the hike earlier than most, setting out from Georgia in January. In North Carolina, Ostrem stopped for the night in a women’s dormitory, and inside was the first female thru-hiker she’d seen on the trail. It was Wernstedt-Lynch.

The two became fast friends and spent much of the next 2,000 miles together, braving snowstorms in the Smoky Mountains and hitching to town for breaks. After the AT, Wernstedt-Lynch completed the Pacific Crest Trail, while Ostrem tackled two different thousand-mile routes in Colorado and Utah. In 2016, they were both working at a ski school in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, and began discussing the next big hike. The Continental Divide Trail was the obvious choice, but as they started to plan, they realized their hearts weren’t in it. The country was still adjusting to the soon-to-be presidency of Donald Trump. “It felt really wrong and go out and disappear into the wilderness for five or six months,” Ostrem says.

So, late one night, she sent Wernstedt-Lynch a text: “What about walking the border with Mexico?”

As they began to consider the idea more seriously, they couldn’t find anybody who had thru-hiked the border before. Mark Hainds, a researcher from Alabama, spent three years linking together various sections, and several people had canoed the length of the Rio Grande along the Texas-Mexico line. But the possibility of being “the first” had little to do with their mission. Their goal was to cut through the heated rhetoric and fearmongering associated with the southern border. The Obama administration deported more immigrants than all 20th-century administrations combined, and Trump, who kicked off his campaign by calling Mexicans “rapists,” was carried to the presidency with chants of “build the wall!”

As Ostrem puts it, “We were trying to explore this really sensationalized issue and make it a personal experience by developing a personal connection to the area.”

Walking seemed a perfect method for achieving those ends. “Long-distance hiking has always been a really motivating force in my life,” Wernstedt-Lynch says, “and it has always felt internally focused. We wanted to see if there was a way to have more of an outward focus to our hiking. So, rather than trying to withdraw from society, we wanted to encounter communities that we maybe didn’t know much about beforehand.”

Two days after the Calexico taxi ride, the hikers contacted John Hernandez, an area resident who has worked with the Mexican American Political Association and other nonprofits. Hernandez met Ostrem and Wernstedt-Lynch at a cemetery in Holtville, California, where, until 2009, bodies of unidentified migrants were buried. Hundreds of small brown gravestones were laid out in dirt rows. Many were marked with the names John or Jane Doe, while others were given only a grid number. Hernandez showed the hikeres where older parts of the cemetery had been bulldozed, the simple headstones cleared away. Between 1998 and 2016, nearly 7,000 people died while attempting to cross the border, most of dehydration or exposure. In recent years, Hernandez said, the authorities had taken to cremating the remains and scattering them at sea.

“It seemed like their bodies were treated as trash,” Wernstedt-Lynch recalls. “You felt the presence of all these migrants who had died in the desert.”

Ostrem says the cemetery was “shocking,” but speaking with Hernandez inspired them to stay on mission. “We were taking it one night at a time at that point, just trying to get through,” Ostrem remembers, “but every day there was a little spark that sent us to the next day.”

As days turned into weeks and the winter slid to early Southwestern spring, the sparks (and shocks) kept coming. The hikers’ blog entries, which amount to more than 400 pages, record each day in detail. While hitchhiking in the Imperial Valley, they were picked up by a bus of farm workers. In California, they carried 18 liters of water (weighing 36 pounds) into the backcountry for a migrant water drop with the activist group Border Angels. More than once in Arizona, Border Patrol spotlights were directed at their tent at night. They filled their water bottles in algae-choked potholes, gas station sinks, and rusty cattle troughs. One evening, Ostrem helped a hotel owner who had recently been granted U.S. citizenship navigate the byzantine process of applying for a passport. Phone calls with ranchers, asking for permission to cross private property, led to dinner invitations.

“Walking is a peaceful way of moving through an area,” Wernstedt-Lynch says, recounting an evening on a highway in Texas when a concerned driver stopped with a Styrofoam box of steaming tacos. “People are generally pretty welcoming to those who are walking.”

But that’s not to say the hikers were naive about potential run-ins with smugglers or human traffickers. “Our main rule while camping is don’t get in anyone’s way,” Ostrem told me three months into the six-month trip. They often set up their tent in thickets of brush away from migrant trails and hidden from view. Even in the winter months, when darkness fell at 5 p.m., they were careful not to illuminate their tent by using a light inside. In between their sleeping bags, they laid out an array of what Ostrem called their “safety doodads”: an air horn, pepper spray, a church key, two GPS devices with SOS buttons, and a flare gun to notify Border Patrol in the event of an emergency. (Though they never needed to use any of them.) With a total of 19,400 Border Patrol agents currently employed—the equivalent of ten agents for every mile of border—the feeling of being monitored followed them through the trip.

Over the miles, they watched the wall change from an imposing concrete barrier to a simple barbed wire fence to a sturdy iron grid that allowed them to wave at Mexicans on the other side. (Both hikers would later say their biggest regret from the trip was their lack of Spanish fluency.) Roughly 700 miles of fencing already exists along the border, with more being added in 2018. In February, a federal judge ruled new sections of the wall need not conform to environmental laws, and the Trump administration is continuing to pressure Congress to fund a complete border wall, which could cost $70 billion.

In late January, the hikers reached the Texas line, the rough midpoint of their journey, where the border begins following the sinuous path of the Rio Grande. The wall disappears completely for long stretches, but canyon cliffs, riverbanks choked with invasive cane, and foreboding desert north and south of the border create a series of natural barriers. “It’s hard to imagine where a wall would go,” says Ostrem, echoing the former head of Customs and Border Protection who told ABC News last year he didn’t think a border wall was “feasible” due to rugged terrain and private property.

One such section, an area in southwest Texas known as the Forgotten Reach, made Ostrem and Wernstedt-Lynch particularly nervous. They’d received permission to walk through several massive ranches, but the area felt more remote than anything they’d experienced so far.

As they stopped to set up camp along a dirt road one evening, Ostrem noticed her phone had slipped from her pack somewhere on the trail. It contained her journal notes from the last section, along with photos and videos that she hadn’t yet posted to the blog. She grabbed a GPS and began jogging back toward the last place she’d used her phone. Almost three miles later, she was still searching when a few rocks tumbled down the slope above. Ostrem froze in fear. “I knew right away it was a person,” she recalls. “This was my worst nightmare, because Claire and I hadn’t been apart [in the backcountry] since the trip began. I was really panicky, but I didn’t see anyone.”

Ostrem kept running, found her phone, and turned around as dusk set in. When she passed the spot again, she saw what had caused the sound: a man in black clothes and a beat-up cowboy hat crouched among the rocks. Although he didn’t move, Ostrem knew he’d seen her. For months, she’d been imagining this type of encounter with a migrant, but now that it was happening, it was nothing like she’d anticipated.

“He was definitely more scared than I was,” Ostrem remembers. “I felt [the border hike] was frivolous compared to what he was doing.” As the migrant moved out of sight, she realized that help wasn’t one press of the SOS button away for him. “It removed me from my own fear to realize someone else was in a worse situation.”

On May 12, 175 days after leaving San Diego, Ostrem and Wernstedt-Lynch walked along the final bend of the Rio Grande and waded into the Gulf of Mexico. They popped a bottle of champagne among a crowd of fishermen on the American side. Across the river, Mexicans stretched out on beach towels as music blasted from car stereos.

In the weeks that followed, the cities they passed on their trip—Brownsville, El Paso, Tucson—were in the headlines nearly every day. Each was the site of child detention centers for minors forcibly separated from their migrant parents under Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ new “zero tolerance” policy for those claiming refugee status, which the Trump administration claims is being abused. While Ostrem and Wernstedt-Lynch don’t think their hike gave them any special insight into the plight of separated families, they do think a “culture of fear” leads to a contradictory deadlock where refugees fleeing gang violence in Central America are barred from seeking asylum because of fears that immigrants bring gang violence with them. “It’s insane that we’re treating anyone crossing the border as one stereotype,” Ostrem says.

In the end, the hikers hope the fact that they were able to walk the length of the border without incident will serve as one small counter to that culture of fear. “I don’t think we got lucky,” Wernstedt-Lynch says. “If other people did this trip, I think the probability would still be very high that there would be no violent or seriously alarming incidents.”

For the hikers, the borderlands have become infinitely more complex and humanized than they ever appeared on the news. Ostrem quotes a line her 93-year-old grandfather told her at the outset of the trip: “I’ve been a lot of strange places in my life, but once I went there, they weren’t so strange anymore.”

You May Also Like

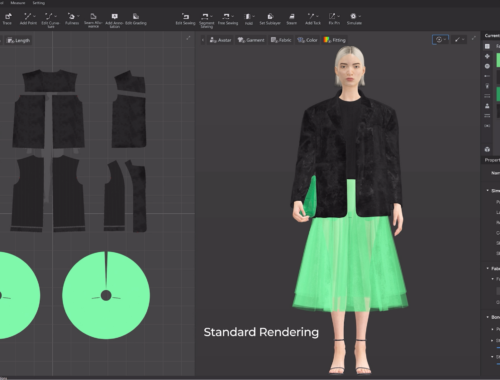

AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion

February 28, 2025

Escape Road: A Journey to Freedom

March 21, 2025