The Dirty Secret Hiding in Your Carbon Mountain Bike

Riding bikes may be green, but the manufacturing behind them can be far from it

Last January, Leo Kokkonen, founder of Finland-based Pole Bicycles, visited China in search of a frame manufacturer, the final step of a two-year-long project to design, test, and launch the company’s first carbon-fiber mountain bike.

Founded in 2013, Pole quickly made a name for itself among critics after its Evolink bikes—known for their long wheelbase—took top honors in the industry’s 2017 Design and Innovation Awards. The rollout of a carbon frame was supposed to be the next logical step to put Kokkonen’s startup on the international map in an industry where carbon is the new king.

By the time Kokkonen boarded his flight home to Finland, however, he’d made up his mind to pull the plug on the whole project.

“It wasn’t just one thing. It was many,” he says, recounting how his lungs burned after an easy ride outside Dongguan, China, where coal-fired power plants cast a cloud over the industrial city. At the factory that was to make his frames, Kokkonen saw just how much water, electricity, and human labor is required to lay, mold, and bond the carbon, a process that entails working with toxic resins. Then there’s the waste. “We knew that carbon fiber is not recyclable, but our idea was to create a frame that was indestructible, so at least we could increase the product lifespan,” Kokkonen says. But when he asked what the facility did with the excess carbon trimmed off each frame—about a third of every carbon sheet is wasted—he was shocked by the answer: “They said they dump it in the ocean.”

Kokkonen isn’t the first person in the bicycling industry to question the environmental effects of carbon. Whereas the more commonly used aluminum can be easily melted down and reformed, the source of carbon’s strength—microscopic fibers covered in epoxy resin and cured at high temperatures—makes it prohibitively difficult to reclaim.

Researchers are working on ways to improve carbon recycling, but the field is still nascent, and the process far from perfect. The resin typically used to bond the carbon fibers together is not only toxic, but also has to be burned off or chemically dissolved to return the fiber to a reusable state. And because recycled carbon fiber can’t bear the same loads as virgin material, it can only be used by the aerospace, automobile, and bicycling industries for nonstructural, injection-molded parts.

Carbon recycling facilities have cropped up in the United States and Europe, but they are not widespread in Asia, where 99 percent of bikes sold in the U.S. market are made, according to the National Bicycle Dealers Association. So when waste gets trimmed during the manufacturing process, odds are it ends up in a landfill—or, as Kokkonen learned, the ocean—where the nonbiodegradable material simply remains. Forever.

That’s why, in 2010, Wisconsin-based Trek Bikes partnered with the South Carolina recycler Carbon Conversions to recycle the carbon prototypes, damaged frames, noncompliant parts, and waste coming from its U.S. manufacturing facility. Even so, the carbon Trek manages to recycle each year represents a small fraction of amount it uses: Most of its bikes are made in Asia, where the company says it is actively investigating recycling programs.

California’s Specialized Bicycle Components also piloted a carbon recycling program in 2015 but ended it the next year because there wasn’t enough demand to make it profitable for the recycler. The company has set up a pilot program in Germany with a recycler that has developed a way to preserve the original fiber, and Specialized is exploring new recycling options for the U.S. market. “Until then, any frame returned to SBC or our dealers is being stored in our Salt Lake City warehouse,” says Troy Jones, the company’s corporate social responsibility manager, formerly a compliance manager at Outdoor Research and REI and the first chairperson of the Outdoor Industry Association’s fair labor working group. “No frames returned to SBC are being disposed of in a landfill.”

In 2014, Specialized partnered with bicycle component manufacturers SRAM and DT Swiss and Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment to research the environmental impact of bicycle manufacturing. Unlike some corporate-backed reports, this one did not give its partners a pass, noting that the industry had “done little to address” the environmental impact of making bikes.

The study compared Specialized’s carbon Roubaix road frame with its aluminum Allez. Based on waste and water and electricity use, the results slightly favored the aluminum frame, and the researchers recommended that bike manufacturers collaborate, as other outdoor product makers have, to create best practices, keep better data, and measure their impact.

To that end, Specialized and SRAM are part of a handful of brands to join the World Federation of Sporting Goods Industry’s Responsible Sport Initiative, launched in 2013, to share information about suppliers and use their collective influence to effect change. The brands receive a list of facilities where they overlap and then divide and conquer by auditing those plants. When the group identifies an area that needs improvement, “the request carries more weight because the factories know it is coming from more than one brand,” says Specialized’s Jones.

While the group is focused on a range of issues, including the environment, most of the changes so far have been focused on labor, health, and safety. For example, the Responsible Sports Initiative required manufacturers to provide protective equipment for their workers and identified ways to minimize the carbon-fiber dust churned up in the sanding process.

Still, with a relatively small list of active members, including Accell Group, FSA, MEC, Pon, and REI, the bike-specific program has only scratched the surface. Of the roughly 260 suppliers Specialized has identified in its supply chain, only 41 overlap with other bike and component manufacturers.

Bike and component makers of any size can make a difference, says Jones, if the industry works together. “I applaud Pole for starting the conversation,” he says. ”A lot of their concerns are valid…but I think they would do more if they stayed and tried to make an impact.”

When it comes to the world’s worst polluters, the bike industry is hardly the biggest offender. Bikes and other sporting goods made with carbon represent a sliver of total carbon demand. According to data from Composites Forecasts and Consulting, only 11 percent of carbon fiber goes to consumer products. The rest goes to make automobiles, pressure vessels, airplanes, and other industrial uses.

“One blade of a wind turbine could produce a year’s worth of carbon frames for us,” says Eric Bjorling, a spokesperson for Trek. The company did its own environmental study, examining everything from the distance between suppliers to its packaging materials. “It’s not one big thing,” Bjorling says. “It’s the sum of all the things.”

Meanwhile, most consumers probably aren’t giving it that much thought. On the sales floor of River City Bicycles in Portland, Oregon, questions about the carbon footprints and supply chains don’t come up at all, says owner Dave Guettler. “The issue has been raised on a minor level from the industry, but consumers aren’t putting pressure on the industry,” he says. “I think most people, when they get into bikes and how they’re made, would have a hard time pointing fingers, considering the environmental impact most people’s lifestyles produce.”

That may be, but it doesn’t exonerate companies, says Kokkonen. Before he pulled the plug on Pole’s carbon frames, Kokkonen looked back at his original business plan. “I wrote a line that says: ‘We don’t want to do unnecessary harm,’” he says. He tries to apply that philosophy to every part of his operations, from keeping marketing materials and swag to a minimum to shipping finished products in repurposed packaging from suppliers.

“We aren’t going to save the world by making Pole noncarbon,” Kokkonen says. “But this is an ethical choice.”

Jay Townley, a partner in the Gluskin Townley Group, a U.S. consultancy that researches the bicycle market, shares that sentiment. When he visited a factory in the late 1980s, the tour came to the area where the resin was applied. Townley said his guide took him by the elbow, turned him around, and said, “We are not going in there without a respirator.” The employees, Townley noted, were not wearing respirators.

Townley has since visited facilities in Taiwan, where he says conditions have improved and employees are now properly equipped. Still, as production has shifted to other countries, including China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Bangladesh, he says, there is no guarantee that any such standards are in place. “I made a conscious decision I won’t buy carbon unless I’m absolutely sure [of its origins],” Townley says, acknowledging that for most consumers, this is impossible. “I don’t think there is any excuse or reason for a product to be made that not only harms the people who make it, [but also] probably can’t be recycled.”

When he visited China, Kokkonen says, it was made clear that he would have little say in how his frames would be made, let alone how employees would be treated or how the waste would be disposed. Instead, Kokkonen, who outlined Pole’s position in a September blog post, is doubling down on aluminum and has plans in place to start building high-performance aluminum bikes on demand in Pole’s own facility in Jyväskylä, Finland, by early next year. The success of his Evolink series, he argues, is proof that aluminum, if designed right, can go head-to-head with carbon on the trail.

Which is not to say that Kokkonen faults anyone who does buy carbon. “We don’t want to be part of the problem,” he says.

Sarah Max covers business and cycling from Bend, Oregon. Eric Nyquist (@ericbnyquist) is an American artist working in Los Angeles.

You May Also Like

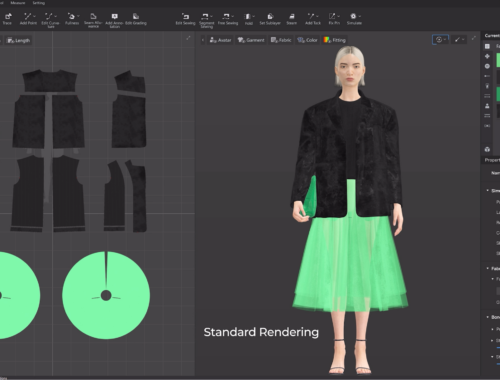

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

トレーラーハウスで叶える自由なライフスタイル

March 17, 2025