The curious case of the ancient whale bones

Every year, thousands of whales strand — meaning that they wind up trapped on beaches or in shallow waters — and it’s really hard to figure out why.

It’s not for lack of trying. Teams of forensic researchers investigate stranded whales, studying organs, analyzing body parts with CT scanners, digging through stomach contents, and checking skin for scarring. But these meticulous whale detectives still often don’t find any answers.

“We can only about 50 percent of the time, if that much, give you a solid answer of why that animal died and why it’s stranded,” says Darlene Ketten, a marine biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who refers to her work as “CSI: The Beach.”

One reason it’s hard to figure out how whales die is that scientists don’t know that much about how they live, Ketten explains on the latest episode of Unexplainable, Vox’s podcast about mysteries in science. They range widely across the planet and dive deeply. There are many things about their complicated bodies we don’t yet understand. And these researchers are often working with whale carcasses that have been decaying for days, which can distort the evidence left behind.

Some beached whales are even more difficult to study because they’re really, really old. In 2011, Nick Pyenson, the curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, took on a cold case that had gone unsolved for a long time — seven to nine million years, to be precise.

Pyenson, who is also the author of Spying on Whales, was on a research trip in the Atacama Desert in Chile, a beautiful expanse of rock and sand that’s flecked with orange, beige, and purple because of the presence of iron and other minerals. He was there to research the origins of a nearby ocean current — but along the way, he got distracted.

“There’s all these whale skeletons by the side of this hill,” Pyenson says one of his colleagues, Mario Suarez, told him one day. “You need to check it out! It’s amazing!”

The hill was known locally as “Cerro Ballena,” or “Whale Hill,” because fossilized whale bones had been found there in the past. Bulldozers had just come through to cut a path for a new highway, and they exposed more skeletons. When Pyenson went to look, he was completely overwhelmed.

“It was whale skeleton after whale skeleton after whale skeleton, complete from nose to tail. Some of them stretched out almost like snow angels the kids make,” Pyenson recalls. “It’s as if they had died and their skeletons were not disturbed.”

This was almost unheard of: full, beautifully preserved skeletons, stretching out for 40 feet in every direction. “In the field, you spend a lot of time searching, and often times you just find a boulder with a few bits of bone — and that is a good day,” Pyenson says. “A really good day is finding more than just a few bits of bone, or a partial skeleton. If you find a head with that skeleton, that’s a home run.”

Once he’d processed what he was seeing, Pyenson realized that he was going to have to start a whole new research project to figure out what exactly had happened to these whales. It seemed like an ancient stranding — possibly one of the best-preserved ones — but it wasn’t going to be easy to solve. There were no tissues to study, so he couldn’t analyze organs or skin, as Ketten and her fellow researchers do with modern whales. Fossilization also changes the minerals in the bones, and rock layers compress them into new shapes, so the bones were somewhat unreliable witnesses.

Pyenson and his colleagues used 3D-scanning technology to make models of the whale skeletons to study them back home. They carefully analyzed the soil and layout of the surrounding area, and finally landed on three big clues.

First, the skeletons were entangled in each other and almost entirely unscavenged, which suggested that these animals had died suddenly. Second, there were many species at this ancient graveyard — whales, but also other adult and juvenile animals, which told Pyenson that the die-off was not limited to whales.

The third big clue came from a close study of the local geology, which suggested these creatures had died in four separate events over the course of around 10,000 years. So whatever was killing the whales had happened several times. That essentially ruled out an infrequent natural disaster like a volcanic eruption.

Pyenson began thinking about cyclical changes to the ocean that could kill off lots of different animals, and fast. “I started moving towards the idea of harmful algal blooms being a cause,” he says. Algal blooms, or red tides, are troublesome to this day. They occur when populations of microorganisms explode in a body of water — sometimes when agricultural runoff floods a lake or ocean with nutrients like nitrogen. These tiny organisms can produce toxins that can prove very deadly, very quickly.

Pyenson theorized that runoff from mineral-rich surrounding areas — minerals that still lend the sands of the Atacama their vibrant colors — could have periodically caused algal blooms in the ocean that once covered this area. But he wanted evidence that would hold up in the court of scientific opinion.

If this were a fresh crime scene, he could have rooted around in the whale’s guts, found a bunch of toxins, and caught the red tide red-handed. But because his crime scene was millions of years old, he could only study his photographic models instead. Those kept showing that the whale skeletons were surrounded by rings of orange sediment — mats of iron oxide, which Pyenson interprets as possible algae in the fossil record. “I kept on wondering, is this the algae of death?” Pyenson says with a laugh.

His team brought samples of this orange sediment back to the US and examined them under an electron microscope. The images included tiny spheres that were the right size to be an algae of death, Pyenson says, but all their distinguishing features had been wiped away by millions of years.

“We are so close to a smoking gun,” he says. “It’s tantalizing. But that’s how a lot of historical science goes. You struggle with it and you want to get at the answer. But sometimes the evidence you’re able to find to answer your questions is not entirely satisfying.”

Jeremy Goldbogen, a marine biologist at Stanford University, read Pyenson’s paper in 2014 and told the journal Science that the positions of the various skeletons seemed consistent with a stranding.

David Caron, who has researched algal blooms at the University of Southern California, was also asked about Pyenson’s research in 2014 and told National Geographic that present-day algal blooms also wipe out a wide range of marine animals. “There’s certainly thousands of sea lion deaths, dozens to hundreds of dolphins, untold hundreds of pelicans that all have been wiped out with the same toxic event,” he told the magazine.

According to Pyenson, these parallels between the past and the present flow in both directions. “I find studying past worlds to be a kind of time travel,” he says. “You get to go these past worlds that almost seem like alien worlds.”

Even if he’s never able to definitively pinpoint what happened at Cerro Ballena, Pyenson says the site suggests that whale strandings were occurring millions of years before modern humans evolved. That’s helpful context for researchers who are trying to prevent strandings in the present day.

For example, a large proportion of the fossils come from baleen whales, even though baleen whales make up only a small fraction of whale strandings today. So what’s changed between then and now? For one thing, centuries of whaling have decimated populations of baleen whales, Pyenson says.

These strandings have been happening “ever since there were whales,” says Ketten. But humans are now contributing to the problem, whether through whaling, plastic pollution, or climate change. “What we have to be responsible for is actions that we take in the ocean that may be … causing animals to become less fit, to be less healthy, to be less able to reproduce, to mate, to find food.”

Whale fossils like the ones Pyenson studied in the Atacama Desert can serve as a sort of snapshot or baseline, revealing how whale strandings looked before humans ever came along. And more researchers can establish about the distant past, the more they may know about the effects that humans are having on these majestic mammals.

You May Also Like

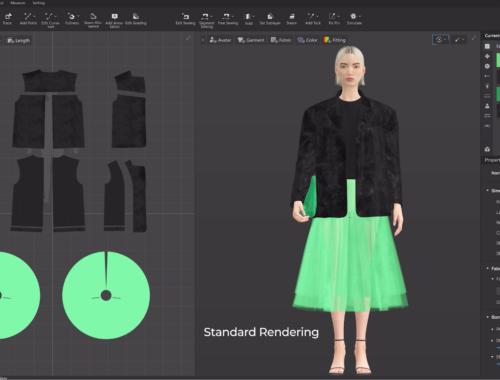

**AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability**

February 28, 2025

Sprunki: A Comprehensive Exploration of Its Origins and Impact

March 19, 2025