The Crusader Protecting Kid Athletes from Sex Abuse

Over the past three decades, Nancy Hogshead-Makar has established a reputation as the leading attorney and champion for young athletes filing sex-abuse lawsuits. Now the former Olympic swimmer faces her biggest challenge yet: making sure #metoo’s impact is permanent.

They lined up shoulder to shoulder, behind Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein. Four tiny former Olympic gymnasts, now adults, each alleged victims of abuse at the hands of coaches. Standing alongside them was Nancy Hogshead-Makar, attorney, Olympic swimmer, and CEO and founder of advocacy organization Champion Women. The women were gathered at a press conference to mark the passage of the Protecting Young Victims from Sexual Abuse and Safe Sport Authorization Act on January 30, which was sponsored by Feinstein and designed to afford athletes of all ages the protections against abuse that have long been missing from amateur sports. The moment represented years of work by Hogshead-Makar, a tireless advocate for young female athletes who need it most. “The passage of this statute is just the beginning,” she says. “Abuse is in every single sport, but we now have protection for 8 million children.”

Hogshead-Makar, 55, brings a passion that stems from personal experience. An Olympic swimmer who won gold and silver medals at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, she understands how hard athletes must strive to reach the pinnacle of their sport. She also understands sexual abuse. In 1981, during her sophomore year while on a swimming scholarship at Duke University, Hogshead-Makar went running just before Thanksgiving break. A man grabbed her, pulled her into the woods, and raped her. Though she reported the rape to authorities, the police were never able to find her attacker.

The emotional toll was overwhelming. “It brought me to my knees,” she says. “I dropped out of swimming for a year, really thinking I was retiring. But then my coach told me I had to come do one practice in order to keep my scholarship.” Hogshead-Makar soon found her competitive drive returning. “My coach knew what he was doing,” she says. “Swimming became therapeutic, and I got back in shape quickly.”

The rest might have been history—moving on to the Olympics, then to law school—except for a visit from former Olympic swimmer Donna de Varona during the 1984 Los Angeles Games. Speaking to the Olympians about Title IX—the 1972 federal law that ensured, among other things, equal treatment and funding for female sports—de Varona awakened an advocate in Hogshead-Makar. Soon after, opportunity knocked. “In the summer before my senior year at Duke, I started interning at the Women’s Sports Foundation (WSF), and all the leaders in women’s sports were on the board,” she says. “They started opening doors for me.”

Hogshead-Makar’s impact over the years cannot be understated, says Rebecca Carlson, head women’s rugby coach at Quinnipiac University. “There are incredibly powerful and moving figures throughout the timeline of the fight for equality. Most of us can only read about them in the history books. For anyone who knows Nancy and her work, we have the privilege of witnessing the same robust leadership and passion in real time.”

Hogshead-Makar moved up through the ranks at WSF, serving as board member from 1985 to 1990, vice president from 1990 to 1992, president from 1992 to 1995, legal adviser from 2003 to 2010, and senior director of advocacy from 2010 to 2014. In her 30 years there, she worked on a wide array of issues, tackling coach-on-athlete abuse, Title IX enforcement, and athlete protections from harassment and assault. Along the way, she also litigated on behalf of athletes in numerous sports to keep well-known abusers out of coaching and administrative roles.

Christine Tuzi is one of those athletes. From a young age, Illinois-based Tuzi loved volleyball and had the drive and talent to match her passion. In 1984, at age 16, Tuzi met the coach she hoped could take her all the way to the Olympics. Rick Butler listened to her goals and told her he could make her dreams come true. Instead, in 1995, Tuzi came forward with two other players alleging that Butler gave her years of nightmares in the form of sexual abuse, lasting well into college. Thirty years later, at age 50, she still struggles. “There are days where my experience sends me into a tailspin,” Tuzi says. “I have to fight off going to a bad place. I cry in the shower and run, swim, or bike to work out my rage.”

In this age of reckoning, Tuzi has reason to hope the future will look different for young athletes. “I’ve noticed I don’t slip backward as much anymore,” she says. “It’s not as common for me to get that pit in my stomach, that feeling that I’ve done something wrong and will be punished for it. I try to find the positives, and most days now, I can control it.” Tuzi gives part of the credit for that progress to Hogshead-Makar, who took up the cause against Butler in 2015 on behalf of Tuzi and several other women who allege that he assaulted them in the 1980s and 1990s. (Butler adamantly denied these allegations in a statement to the Chicago Sun-Times.)

In 1995, USA Volleyball banned Butler from coaching, but the organization partially lifted the ban in 2000, making him one of many coaches who, in spite of receiving bans from their sports, wind up back near the playing field, gym, or pool. (USA Volleyball permanently banned Butler this year.) According to Hogshead-Makar, “When Butler threatened to sue USA Volleyball, the organization did not have the insurance to defend against a suit like this. This is why we worked to pass legislation that protects the athletic organizations against lawsuits like his.”

In February, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU)—which serves as an umbrella organization over volleyball and many other U.S. amateur sports—removed Butler as a member and permanently disqualified him from participating in AAU activities. His removal follows numerous allegations of sexual contact with underage girls. As reported by ESPN, the AAU launched an independent review in 2015 and asked Butler to step aside during the review. Nonetheless, in the ensuing years between his original USA Volleyball ban and the AAU ban, Butler continued to coach for multiple clubs.

Hogshead-Makar campaigned hard for the organization to enforce his ban. She launched an online petition, gathering thousands of signatures, and sent letters to more than 90 volleyball clubs alerting them that Butler was still on the sidelines working as a coach for hundreds of young women and in proximity to their players during matches. “We also wrote to Disney, where the national championships were held that year, to let them know he’d be on their property, and over 40 athletes wore ‘ask me why’ T-shirts to the event,” she says. “One by one, all the AAU sponsors pulled out.”

“When the AAU and USA Volleyball allowed him to coach again after a lifetime ban, Nancy led the charge to see that his ban was enforced,” Tuzi says. “It was the first time someone with power cared about what happened to his victims.”

Stories of coaches accused of abuse who remain working in their sport are common. This is particularly prominent in Olympic and club sports, where, until the recent passage of the Safe Sport Act, there were no central guidelines to protect young athletes.

There were steps along the way, however, that helped: In 2012, under pressure from Hogshead-Makar and coupled with the rising voices of well-known gymnasts, swimmers, and other athletes, the U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) passed a board resolution requiring all of its national sports governing bodies to prohibit romantic and sexual relationships between coaches and athletes, regardless of age and consent. “In Rick Butler’s case, he deftly moved to another sports organization after getting banned by USA Volleyball,” Hogshead-Makar says. “USA Volleyball left it to a regional division to enforce its ban; the group did not have the resources to fend off Butler’s litigation threats, so it was easier for them to allow him back into USA Volleyball as an administrator.”

Under the new law, all youth sports organizations must report sexual abuse allegations to law enforcement within 24 hours, rather than leaving it up to the organizations to handle cases internally.

In addition, and perhaps more important, the Safe Sport Act provides USOC, national governing boards (NGBs), and clubs with immunity from defamation claims by those removed from sport for violating sex-abuse policies. The act requires a minimum of $150,000 in damages against someone, delivered to the charging victim, after they have been found to have committed sexual abuse in a civil suit.

“Criminal laws have always been around, but they are poorly suited to deal with child sex abuse,” Hogshead-Makar says. “Beyond a reasonable doubt, all the criminal protections mean not many abusers will see a day in prison. Nevertheless, this new law will prevent accused coaches from threatening expensive lawsuits that the NGBs and other organizations cannot afford to defend.”

Before, the governing bodies saved millions by leaving accused coaches in place. “The U.S. Olympic Committee wanted to save money, period,” Hogshead-Makar maintains. “The organization didn’t spend money on investigations, education, background checks or investigating lawsuits. The Olympic movement, including administrators and coaches, have adamantly denied protecting athletes from pedophiles, leaving it to parents, clubs, and the police.”

Hogshead-Makar has also worked against the system in her own sport. Former swimmer Jancy Thompson, 36, says that in California in 1995, her coach began grooming her for abuse at the age of 13. Similar to Tuzi, Thompson had Olympic dreams. “He had total control over me and sexually abused me for many years,” she says. “Eventually, I was a shell of my former self.”

Thompson learned about Hogshead-Makar from her lawyer, Robert Allard, and the two formed a partnership to advocate for change within the swimming culture. “I wanted to understand how she got to the place she has,” Thompson says. “I admire her willingness to keep fighting.”

While successful on many fronts, Hogshead-Makar’s legal and legislative battles over the years haven’t been without frustration. When her former U.S. Olympic team coach Mitch Ivey received a lifetime ban from USA Swimming in 2013, it was the culmination of decades of work. Hogshead-Makar had been sexually harassed by Ivey, and “he was a well-known abuser for years,” she says. “But it took congressional scrutiny of the organization before the case went anywhere.”

In 2014, Hogshead-Makar petitioned to prevent the induction of Chuck Wielgus, former executive director of USA Swimming, into the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Representing 19 women, Hogshead-Makar pressed hard to demonstrate that under Wielgus, countless coaches had abused their swimmers. “We also helped ensure that USA Swimming changed its laws surrounding sexual misconduct,” she says. “Now USA Swimming has one of the best policies in the country, imposing stricter background checks and penalties for sexual misconduct.”

Still, the wheels of justice often spin slowly. “Any profession where there is a power relationship—priests, coaches, prison guards—should have very strict rules and oversight to prevent abuse,” Hogshead-Makar says. “Instead, the culture has allowed young girls to be molested under the guise of ‘dating.’”

As Hogshead-Makar says, abuse allegations exist in every sport. In 2014, she joined forces with Bridie Farrell, a short-track speedskater who came forward in 2013 at the age of 31 to accuse her teammate Andy Gabel of alleged sexual abuse. Hogshead-Makar championed the effort to remove Gabel from the board of U.S. Speedskating and worked with Farrell in an unsuccessful bid to remove him from the Speedskating Hall of Fame.

The two women together attended a USOC event to train the Olympic movement on Safe Sport policies. Farrell handed out postcards to everyone in attendance. On them, she included her picture and details of her story. “After I passed the postcards out, I scribbled a note to Nancy, asking ‘What did I just do?’” Farrell says. “But Nancy told me I had this, and just as importantly, that she was with me.”

Hogshead-Makar left the WSF in 2014 to continue to push for an independent entity for Safe Sport, as well as a statute that would protect athletes from sexual abuse. “The USOC tried to dissuade the WSF from pursuing these efforts, because they were staunchly opposed to the policies that female athletes wanted,” she says. “Ultimately, it’s because of the cost, but they also didn’t want it to be their responsibility.”

This led Hogshead-Makar to form Champion Women, her own advocacy organization for women and girls in sports. She then spearheaded the push in Congress to protect athletes by federal statute. Her efforts included collecting 55 organizations and 183 sport and child protections experts who threw their support behind the legislation. All of this led up to that moment in January alongside the gymnasts, when Congress instituted new protections for athletes participating in club and Olympic sports.

Hogshead-Makar also advocated for the resignation of USOC CEO Scott Blackmun, which happened in February. As a leader of the Committee to Restore Integrity to USOC, Hogshead-Makar presented the House Committee on Energy and Commerce with documentation that outlined numerous opportunities USOC had to prevent athletes from being sexually abused. “Blackmun’s career will be defined by his unwillingness to protect athletes from sexual abuse within club and Olympic sports,” she says.

To Hogshead-Makar’s line of thinking, Blackmun’s removal is a big first step, but there is much work to do. Through the Committee to Restore Integrity, she is already pressing Congress to amend the Amateur Sports Act to provide athletes with methods to solve conflicts with their NGBs and to provide even greater protections from abuse. Above all else, Hogshead-Makar believes one rule should dominate the others: “Coaches shall not have romantic or sexual relationships with the athletes they coach, regardless of age or consent.”

And in this age of #metoo, Hogshead-Makar feels that real change is on the horizon. “We’ve reached a tipping point,” she says. “Today, women have great role models for speaking out. When you see elite athletes saying they were abused, and that narrative doesn’t diminish their stature, that’s progress.”

For her part, Farrell views Hogshead-Makar as a champion for women in sport. “She has given a voice to me and so many others,” Farrell says. “I think the name of her organization—Champion Women—is a perfect tagline for who she is.”

You May Also Like

Google Snake Game: A Classic Arcade Experience

March 23, 2025

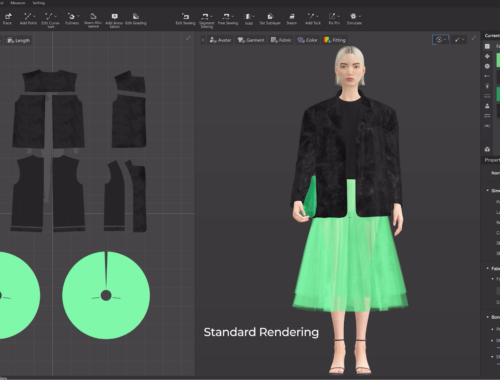

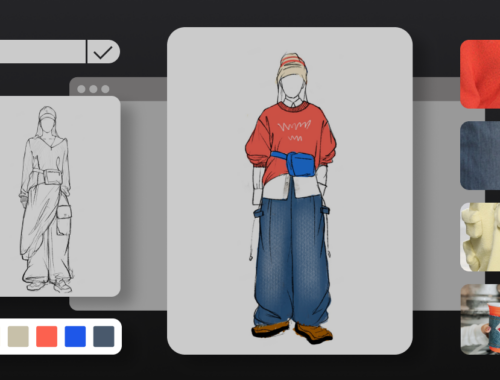

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025