The Case for Not Changing a Thing

Sometimes, when it comes to making progress it’s the smartest choice you can make.

We humans suffer from the commission bias: a preference toward doing something rather than nothing. We’re also novelty-seeking creatures, drawn to bright and shiny objects. These propensities have served us well throughout evolution. Long ago, they drove us to develop useful tools, to hunt even during times of surplus, and to explore new and fruitful lands. Today, they fuel cultural progress and scientific discovery. But our hardwired tendency toward action and novelty isn’t always a good thing; it also makes us prone to make a change in situations where the best thing to do is nothing. This is a trap that is especially common in health and fitness, where patience really is a virtue—and one that is far too often overlooked.

Consider diet. Drawn to the latest and trendiest approach, many people who are trying to lose weight constantly bounce between fads: low-carb, high-fat; low-fat, high-carb; South Beach; Atkins; DASH; Zone; Ornish; intermittent fasting; the list goes on and on. The continual switching (perhaps because you’re searching for a better way or aren’t seeing results quickly enough) is actually detrimental to losing weight. A 2018 study out of Stanford University compared low-fat and low-carb diets, also tracking randomly assigned participants for a year. The best predictor of weight loss wasn’t which diet the participants were assigned to but whether or not they adhered to that diet. Writing about these results in the New York Times, Aaron Carroll, a physician and researcher at the Indiana School of Medicine, explains that “Successful diets over the long haul are most likely ones that involve slow and steady changes.”

A similar trend is prevalent in fitness, too. A 2016 article published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine makes the case that the majority of sports injuries are caused by impatience. “Excessive and rapid increases in training loads are likely responsible for a large proportion of non-contact, soft-tissue injuries,” writes Tim Gabbett, author of the paper and a well-known Australian sport scientist. Gabbett’s research shows that the best way to avoid injury is to slowly build up training volume over time. When acute workload (what you did this week) is more than twice as much as chronic workload (the average of what you’ve done the past four weeks) you’re 5 to 10 times more likely to sustain an injury versus when you make a more modest—say, 10 percent each week—increase in training volume and intensity.

Patience is especially important when returning from an injury. “You have to have patience and respect the process,” says Michael Lord, a sports chiropractor who treats and trains elite athletes in Northern California. “Your body will take some time to adapt and build resilience to the training loads again. You build this resilience by being consistent over a long period of time. One of the major failure points of a rehab program is an athlete who gets impatient and does too much too soon.”

This impatience trap isn’t just about doing too much too soon, but also about constantly switching approaches. Through my work writing this column, I’ve had the privilege of getting to know some of the top athletes and coaches in the world. People like Shalane Flanagan, Rebecca Rusch, Siri Lindley, Alex Honnold, Des Linden, and Kelly Starret. What’s interesting is that they all use different strategies to build fitness. Some follow a high-intensity, low-volume approach. Others the opposite. Some train using heart-rate zones, while others use perceived exertion. And yet they’ve all told me that the key to training success isn’t so much the plan, but whether or not they (or the athletes they coach) stick to it. So long as the training is based on sound principles, the specific method isn’t nearly as important as an athlete’s patience with it. There are many roads to Rome, but you’ll only get there if you stay on the same route.

Of course this isn’t to say you should never switch things up. Sometimes taking a dramatic action, or changing your routine altogether, is exactly what you need—especially if your plan isn’t working. But just be wary of pulling the trigger too soon. Even though we often feel the urge to take action or change things up—to make things happen—sometimes the best thing we can do is simply give it another week or two. Lasting progress in just about any endeavor involves peaks, valleys, and plateaus. And therefore it also involves plenty of patience.

Brad Stulberg (@Bstulberg) writes Outside’s Do It Better column and is author of the book Peak Performance: Elevate Your Game, Avoid Burnout, and Thrive with the New Science of Success.

You May Also Like

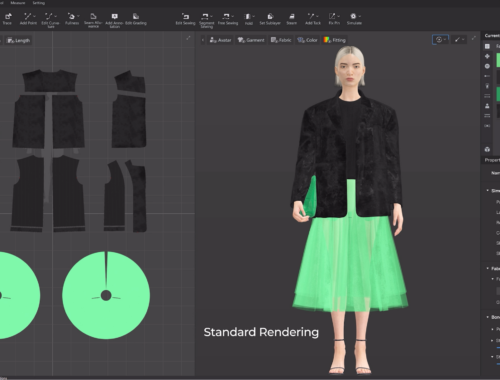

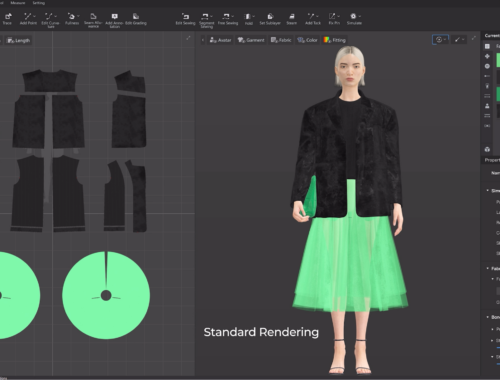

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025