The Boston Marathon Stands Up for Sub-Elite Women

After the craziest race in decades, a controversy emerged about prize money. Luckily, this story has a happy ending.

It’s been well-established that this year’s Boston Marathon was an all-around peculiar day. Adding to the chaos, a post-race controversy emerged about who was entitled to collect prize money, as the high attrition rate among the pros (23 of whom DNF’d) opened the door for less established, sub-elite runners.

Case in point: the second place finisher in the women’s race was Sarah Sellers, a full-time nurse anesthetist whom even running mega-nerds had never heard of. (“Who Is Sarah Sellers?” a Washington Post story asked.) Fortunately for her, Sellers had qualified for Boston in a time fast enough (2:44:27) that she was invited to start with the elite women, who head out of Hopkinton roughly a half hour before Wave One. By running with the elites, Sellers was eligible for prize money. As the second place finisher, she won $75,000.

Many among the top female finishers were not so lucky, however.

As the Boston Athletic Association’s (B.A.A.) website explains, prize money is offered in the marathon to the top 15 finishers in both the men’s and women’s races, as well as the top five Masters (Age 40+) finishers. The caveat here is that for the women, it is only awarded to those who, like Sellers, are given the nod to start in the elite field, which in 2018 consisted of 44 runners. In other words, in the unusual event that a woman who starts with the masses runs a faster chip time than a top-placing elite finisher, the purse stills goes to the elite runner. Conversely, since the elite men start with the rest of Wave One, an amateur male runner who manages to sneak into the top-15 can claim a cash prize.

Due to the carnivalesque nature of this year’s Boston, three non-elite women finished in the top 15 of the “Open” category, and two non-elite Masters women cracked the top five—a historical first. Per the rules, none of these runners were eligible to be compensated for their efforts.

Jumping on the fact that this apparent injustice wouldn’t happen in the men’s race, Buzzfeed ran an article last week with the headline: “This Woman Placed 5th In The Boston Marathon. If She Were A Man, She'd Have Won $15,000.” Vox subsequently ran a similar (if more nuanced) story, which also picked up on how the rules were skewed in favor of sub-elite men. To their credit, both articles cited the Boston Athletic Association’s (B.A.A.) rationale for having a separate elite women’s start, which is standard practice for many major marathons: “As opposed to starting men and women at the same time, and ultimately having the female competitors lose each other among packs of men (and potentially receive pacing assistance), the EWS [Elite Women’s Start] allows athletes to compete without obstruction," T.K. Skenderian, the Communications Director for the B.A.A., told Buzzfeed, adding that having a separate women’s start also allowed for better media coverage of the race.

In the requisite backlash to the backlash, some members of the running cognoscenti were annoyed at how Buzzfeed and Vox were apparently giving the story a battle-of-the-sexes spin.

“This isn’t a gender thing. It’s a competition thing, as in a race to the finish line,” pro and collegiate running coach Steve Magness tweeted. “It's a race. Not a competition to see who runs the best time.”

That’s really the heart of the matter. The non-elite women and the elite women are competing in two entirely separate events, and the B.A.A. only awards prize money for one of them.

Except in 2018. In a move that feels like an appropriate coda to a race where none of the regular rules applied, the B.A.A. announced yesterday that, what the hell, they would also be paying out money to the top-finishing women who started in Wave One. As a consequence, non-elites Becky Snelson (14th place), Veronica Jackson (13th), and Jessica Chichester (5th) will be paid $1,500, $1,700, and $15,000, respectively. On the Masters front, Brenda Hodge (5th) and Joanna Bourke Martignoni (3rd) will receive $1,000 and $2,500. These amounts are equal to what elite runners are paid.

“Given the nature of this year’s race, we want to recognize and celebrate some of the performances that made this year’s race special,” Skendarian said in an email explaining the B.A.A.’s decision.

Following the announcement, I called 13th-place finisher Jackson, a New York-based sub-elite athlete who finished the race in 2:49:41.

“I feel really grateful that the B.A.A. is giving us this money since they definitely don’t have to. This rule [i.e. the separate start for elite women] was only made with the best intention for women, which I think has gotten lost in this discussion,” Jackson says.

She added, however, that this wasn’t the first time she’d missed out on potential prize money because she’d been denied an opportunity to start with the professional women. It’s an issue, Jackson admits, that only affects a very small number of women, but doesn’t affect men at all.

“I routinely miss out on money for this exact reason, when I fully believe I belong in that field,” Jackson said.

It’s worth stating that Sellers probably only got to start with the pros because her qualifying time was just under the U.S. Olympic Trials “B” standard of 2:45:00; there’s no official cutoff time for the pro start and it’s always left to the discretion of race organizers. Sellers wasn’t initially listed among the elites when the pro fields were announced by the B.A.A. in January, and could very easily have been relegated to start with the masses. In other words, one of the best running stories of the year almost didn’t happen.

As Jackson sees it, it’s in the interest of the B.A.A. to give more runners like her a chance. “The fact of the matter is that men don’t face that hurdle. Do I think the B.A.A. should be chided as being sexist? Absolutely not. But I do hope that because of this, sub-elite women who want to be up racing against those women are maybe given an opportunity. What is the harm in doubling the elite field size?”

You May Also Like

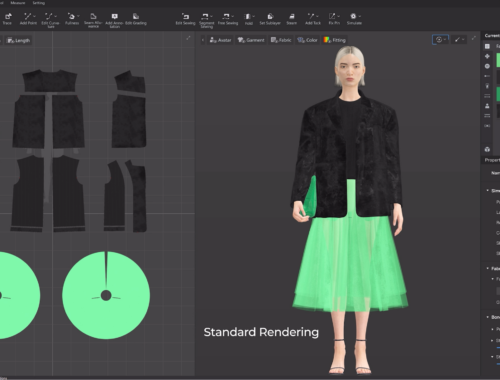

AI in Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining Design, Production, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025

トレーラーハウスで叶える自由な暮らし

March 17, 2025