The Bohemian Heiress Who Shattered 19th-Century Taboos

Badass Women Chronicles

The Bohemian Heiress Who Shattered 19th-Century Taboos

Aimée Crocker sailed across the Pacific, narrowly escaped murder in the jungle, and trounced the sexist and racist norms of her day

Apr 24, 2018

Apr 24, 2018

Aimée Crocker sailed across the Pacific, narrowly escaped murder in the jungle, and trounced the sexist and racist norms of her day

Great journeys often start with a mystery. For Aimée Crocker, the late-19th-century railroad heiress and pioneering adventure traveler, the mystery arose when she was just a small child.

According to Crocker’s 1936 memoir, And I’d Do It Again, one evening in the late 1860s or early 1870s, she bounded up the stairs of her California home ahead of her nanny to discover a surprise. In her room, bathed in silvery moonlight, a ghostly woman lay on her bed, dressed in magnificent silk robes and a gossamer veil unlike any attire the young girl had seen. (She later learned it was the dress of a Hindu noble.) The woman looked at Crocker and smiled.

“She seemed to know me,” wrote Crocker decades later. “It was somehow…I can hardly explain it…as though I knew her, too; as though she were there naturally, as if she belonged to me.”

Unafraid and excited, the girl called for her nanny to come see, but the apparition vanished. The breathless caretaker scolded her, but Crocker’s imagination burned. Who was this woman, and where did she come from? Crocker would spend much of her life searching the world for answers.

Crocker was born to an exceedingly wealthy California family in 1863, a time when women were expected to be docile and content to reside quietly in the background of public life. Meekness, however, didn’t run in Crocker’s blood. Her father was a state Supreme Court judge and legal counsel to Central Pacific Railroad; her uncle was also a railroad titan; and both of her parents were activists, abolitionists, and philanthropists.

Of her half-dozen siblings, Aimée was the wild child, an unapologetic rule breaker and inspiration to nonconformists everywhere. While other women were just starting to venture into European capitals, she was plunging deep into jungles, sailing across oceans, and racing on horseback with locals on Hawaiian beaches. Crocker spurned racist, colonialist, and sexist ideologies; brazenly crossed class boundaries; and embraced non-Christian religions—to the scandal of American high society.

“She was front-page news in major publications around the country for literally 60 years,” says Kevin Taylor, author of Aimée Crocker’s Refined Vaudeville and Aimée Crocker: Queen of Bohemia. “It surprised me that she’s not a household name today, how someone can become lost to history.”

Even by today’s standards, however, Crocker was naive in her moneyed privilege and remarkably louche. She claimed to have had a sexual awakening with a snake, and she had countless affairs in addition to her five husbands. It’s also worth noting that today, some of the remarks in her book could be deemed cringe-worthy and culturally insensitive. Crocker was outrageous and controversial and anything but boring. Thankfully, she was also a captivating storyteller and never let facts hamper a good yarn, especially not her own life story.

Crocker’s escapades started early. After she got a bit too friendly with San Francisco’s sailors as a teenager—they taught her to swear!—her parents sent her to Dresden for finishing school, where she promptly got engaged to a German aristocrat, broke it off, and caught the fancy of a Spanish bullfighter before her family could retrieve her.

Back in the United States, Crocker married the scion of a prominent San Francisco family—who allegedly dueled for the right to her hand—but the relationship quickly ended in divorce. Young, rich, and free from “marriage and other thwarting circumstances,” as she put it, Crocker decided to use her formidable inheritance to buy her own freedom and fulfill her longing to visit distant lands.

At a party in Europe, an acquaintance, King David Kalakaua, invited her to visit his tropical empire. Unannounced, Crocker hired a 70-foot schooner and a rowdy crew of sailors to spirit her across the Pacific to the Hawaiian Islands. She spent months riding in horseback races with the Hawaiians, dancing hula, and happily indulging in nighttime swimming parties off pristine Waikiki Beach, all lit with glowing torches. She lived in a hut, wore the local dress, and befriended a hypnotist. The missionaries were not impressed.

“It appears that they felt I was setting a bad example to the natives they were trying to convert by not acting superior to them,” Crocker later wrote. The king, however, was charmed. He gave her a Hawaiian name and dubbed her princess of a small island.

Fueled by curiosity, Crocker pressed farther west into Asia. In Tokyo, a Japanese baron she had met put her up in a bamboo-and-paper mansion, where she had 30 servants and lived as a 19th-century aristocrat. In Hong Kong, she shacked up with a Chinese feudal warlord who took her to Shanghai on a teak yacht hung with silks.

In Indonesia, Crocker sailed with a Bornean prince to his remote village in the jungle, where she marveled at the profusion of greenery, monkeys, crocodiles, and birds before the locals tried to kill her with poison arrows and a head hunt. (They were concerned the prince was trying to take a white woman as his queen, which he was.) She narrowly escaped by commandeering a dugout canoe and floating the river for days before reaching a Dutch outpost. But it was in Bombay where Crocker finally started to disentangle the mystery that fueled her ten-year exploration of the East.

Her great revelation began with a yogic text that a maharaja gifted her and another fantastical vision she claimed to have seen around the same time. Late one night, Crocker returned to her hotel room and, in a moment of repose, glanced at the mirror and caught a glimpse of something shimmering behind her. She whirled around. In Crocker’s telling, the same beautiful, ethereal woman she had seen as a child lay on the bed. Dressed in fine silk robes and crowned with a ring of pearls, the woman slowly rose, sat on the bed, and reached her hand out to Crocker. Fearless, Crocker took a step forward. The woman vanished.

Shortly after the vision, Crocker learned of an Indian yogin, Bhojaveda, renowned for his ability to explain the mysteries of life and death. She became determined to visit him, eventually traveling to Pune, India, to find him. While many visitors were turned away, Bhojaveda’s attendants inexplicably allowed her to enter his cave, where the old man appeared out of the murky dark. “His perfectly white hair hung to his waist and his beard to his knees,” Crocker wrote. “His skin seemed to be wax, and one could notice that the fingers and the flesh of the face were actually translucent.” According to her telling (which admittedly tests the boundaries of credulity), Bhojaveda spoke to her in a language she didn’t understand, and a vision of a young Indian boy dressed in the robes of a Hindu noble miraculously arose in front of her. Finally, he evaporated, and the yogin turned around and disappeared into the darkness.

Crocker had no idea what to make of the experience, but as she walked away, an attendant approached her and spoke in English. He said that the young boy in her vision was Crocker in a past life, and that the spectral woman she had seen as a child was her mother, who was watching over her. The great mystery of the beyond would remain unknown to her in this lifetime, the attendant said, but she would see the vision one more time—just before her death.

“You may imagine for yourself the effect that such an interpretation had on me,” Crocker later wrote. “I left with a new passion and a new fear.”

Crocker returned to the United States and never traveled to Asia again. But her obsession with the East continued, and her penchant for novel adventures and ideas never dimmed. She collected Buddhas, pearls, tattoos, husbands (including a prince or two), boa constrictors, and famous and eccentric friends. She threw outrageous dinner parties, where she showed up dressed as an Egyptian queen, strode in atop an elephant, gave away chameleons as party favors, and performed her own magic shows.

In 1936, Crocker published And I’d Do It Again to acclaim and shock. The book “swarms with séances, toreadors, Rajahs, sin, and snakes,” a reviewer from the Winnipeg Free Press wrote. The Los Angeles Times called it a “deplorable record.” Naturally, it made for entertaining reading and brisk sales.

Crocker died of pneumonia at the age of 78 in her apartment at the Hotel Savoy Plaza in New York City in 1941. She fell out of the public record for decades, but in 2010, her book was reprinted. She is still criticized for her hedonistic excess, but Crocker’s enthusiasm for life and adventure (“I would try anything once,” she said), disdain for prejudice, and gleeful flaunting of social mores continue to inspire a cult following.

While she was often snubbed as a flamboyant misfit in her own era, Crocker’s appeal endures nearly 80 years after her death. The fashion label Marchesa released a line inspired by her world travels last fall, and in December, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, founded by her family, threw a party in celebration of her birthday. Snake charmers, belly dancers, fortune tellers, and a tattoo artist entertained a crowd of about 1,400.

“I have been accused of living adventurously…and if I have dared to stick my nose into trouble just because the game was fun, does it make me a brazen hussy?” Crocker wrote. “If I could live it again, this very long life of mine, I would love to do so.”

You May Also Like

WHY ELECTRIC TRICYCLES FROM CHINA ARE TRANSFORMING GLOBAL TRANSPORTATION: A GUIDE TO CHOOSING THE BEST MODEL

December 31, 2024

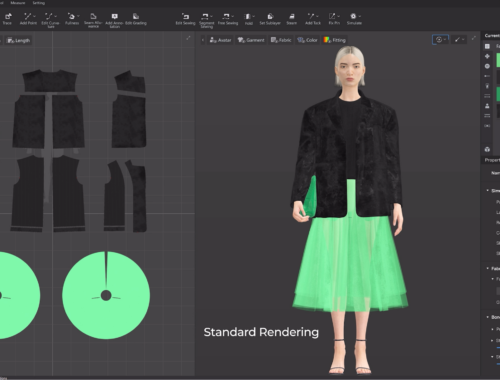

“AI Meets Couture: How Artificial Intelligence is Redefining the Future of Fashion”

February 28, 2025