The Art of Wayfinding

It’s not the bike that matters—it’s where you take it

What’s the best way to get the most enjoyment and satisfaction from cycling? Is it building your fitness? Honing your bike-handling skills? Optimizing your tire pressure? Figuring out how to pee in bib shorts?

Well, these all have their place, but more important than all of them combined is the ability to choose the perfect route. In the age of Zwift it’s all too easy to forget that any hamster can mindlessly crank out watts, and that cycling is above all the art of propelling a bicycle across the landscape. Ultimately, it is the path you travel that determines how enjoyable, exhilarating, or downright transcendent your ride is, and even with the luxury of GPS to help you along, there’s still no substitute for the sort of thorough and intimate understanding of your landscape that lets you act as your own route sommelier.

The Out-And-Back

The lowest form of route curation is the out-and-back. This consists of getting on your bike, riding to some predetermined endpoint, and then turning around and retracing your steps. Out-and-backs are particularly popular with triathletes and other turn-averse people who use aerobars and want to replicate the linear, two-dimensional experience of riding indoors.

This isn’t to say there isn’t a time and place for the out-and-back. After all, your local geography might require it, as might time constraints or unfamiliarity with an area. Fundamentally however the out-and-back is the cycling equivalent of sitting down at a Steinway and banging out chopsticks.

The Circuit

While on the surface of it riding around in circles would seem to be just as simplistic as the out-and-back, the truth is doing laps on a circuit can be stultifying or it can be meditative, depending on how you approach it. As a city dweller who often rides in parks, I’m quite familiar with riding circuits, and I depend on them to inject some bliss into my day. It’s also a quick and easy way to satisfy my need for mileage, just as stopping at a Halal cart and emptying a styrofoam container into myself on the way to the subway is a simple way to knock out lunch.

But while riding in circles in an urban oasis can be contemplative, it can also be maddening if it’s not augmented with other types of riding. Like the sea lion habitat at the zoo, it’s a visually pleasing facsimile of the real thing, but deep down you know the poor suckers are going stir crazy in there. Plus, here in New York we also hold our races in the parks, which is essentially the trainers coming out and making us do tricks for fish.

The Short Ride

Cycling is a time-consuming pursuit, but adept route-planners who are short on time or fitness (if you’re short on one you’re usually short on the other) and have neither the access to a circuit nor the inclination to ride one know how to make the most of a short ride. Cultivating satisfying short rides is a discipline in itself. Like a miniature bonsai forest, the artfully pruned short ride is a shrunken epic that is no less enjoyable for its diminutive size, and in fact it can be even moreso for its sheer preciousness. A steep hill, a sweeping curve, maybe a little gravel—yes, if you make the most of your surroundings it is possible to ride for a mere hour and a half and still return home with that post-ride glow.

The Modular Route

Anybody can ply the same route over and over again or jump in on the group ride, but once you truly master your surroundings and learn every inch of road and trail and how they fit together you can begin to improvise.

Being able to alter your route on the fly while still maintaining a pleasing gestalt will do wonders for your riding life. Sometimes you’re a half hour into your ride only to get a call that your kid is puking in school and you need to pick her up; other times you feel better than you expected and you want to tack on some extra miles or intensity. In the former scenario a poor improvisor might simply turn around, and in the latter one might resort to doing hill repeats. (Appending hill repeats to your ride is tacky, like stopping at McDonalds for fries because you’re still hungry after sushi.) A good improviser however will visualize the landscape and add and subtract segments as necessary, like Tom Cruise using that crazy gesture-based computer system in Minority Report.

Also, one of the greatest joys of cycling is setting out with no particular destination in mind and letting your legs determine the narrative, which is why the most satisfying rides are often the ones where you’re stringing together familiar roads and trails in a way you never have before.

Going Big

While you can subsist indefinitely on a diet of short rides, sooner or later you’re going to find yourself craving a large repast. There’s a right way and a wrong way to go about a long ride. The right way is to keep it varied and interesting, with different courses to savor. The wrong way is to treat it like a speed eating contest where you’re forcing down pedal strokes instead of cannolis. You may want to be able to say you rode X number of miles when you get home, but scale alone does not make something compelling; there’s also mise-en-scène, which is why you know who Chris Froome is but you can’t name a single RAAM winner without Googling.

Exploration

Regardless of how big or small you’re going, by far the most important aspect of becoming route artist is to make a point of trying something new on every ride. Unless you’re under crushing time constraints, every outing should include at least a little bit of reconnaissance. You never know when turning down a road or following a trail will yield a discovery and unlock an entire new set of possibilities. Sure, every so often you might find yourself dragging your bike through a thicket or trying to find your way out of cul-de-sac hell, but there are two kinds of cyclists in this world: the ones who know where the secret trails are, and the ones who don’t.

Or you can just stay hunched over your aerobars, whatever works for you.

You May Also Like

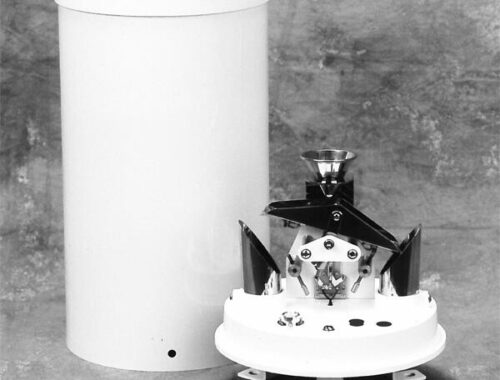

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025

Wind Speed Measurement Instrument: An Essential Tool for Accurate Weather Monitoring

March 19, 2025