The 8 Best Travel Books of All Time

>

When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we earn an affiliate commission that helps pay for our work. Read more about Outside’s affiliate policy.

At their worst, travel books are dated, deeply racist, or just painfully dull. But at their best, they capture the spark of seeing something new, as well as the way your perspective shifts when you’re out of your rut with your eyes open. Here are some of the best—including some by writers who have been overlooked for too long.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s chronicle of his time pioneering new mail routes as an Aeropostale pilot in the 1920s and ’30s is the kind of adventure story that’s too crazy to have been made up. But what really sets it apart is Saint-Exupéry’s clarity about both the minutia of early aviation and his own feelings as he faces his potential death while flying above the empty Sahara. It’s a gripping, gorgeously written window into a world that doesn’t exist anymore. If the early days of flying get you going, Beryl Markham’s West with the Night should also be on your list.

There are piles of American road-trip books, and plenty of them don’t hold up well (ahem, On the Road), mostly by dint of their selfishness. Staring at the windshield trying to figure out your shit stays interesting only for so long. In both Travels with Charley in Search of America, where John Steinbeck, in his old age, takes a lap around the country, and Great Plains, where Ian Frazier tries to understand what pulls him to those plains, the focus is external. They’re fascinated by the people they meet and the way those people shape and are shaped by the land around them. That contrast, and the complicated crew each author encounters, is what makes America—and both of these books—great.

Mark Twain, more than anything, is funny. And his satirical account of his trip on a steamship to Europe and the Middle East is a send-up of privileged Americans, including himself. But between Twain’s character sketches and sarcasm, he digs into why people travel, the ways tourism takes advantage of locals and capitalizes on history, and the baked-in moral conflict of being a traveler responsible for that capitalism.

Hunter S. Thompson has nothing on Zora Neale Hurston’s brand of gonzo journalism. For her in-your-face look at medicine, ritual, race relations, and tradition in Jamaica and Haiti in the 1930s, Hurston, an American woman, had to unflinchingly show up for those rituals, even if it meant getting bucked off a mule in the middle of nowhere or subjecting herself to medicine men. It’s immersive travel writing at its finest.

A really good book can take a subject that you might otherwise think is a snooze (sheep! someone else’s spiritual journey!) and turn it into something relevant and fascinating. The Snow Leopard, Peter Matthiessen’s story about his loosely planned trek into the Nepalese Himalayas with sheep biologist George Schaller, is also a story about why climbers go to the mountain in the first place and what we’re trying to find there.

Eat. Pray. Love. Or something like that. Julia Child’s memoir of her time in France is the best, most joyful version of a certain type of travel story—like Under the Tuscan Sun or Elizabeth Gilbert’s actual Eat Pray Love—where the writer (often a woman) is submerged in a foreign culture and works her way through discomfort, cultural clashes, and awkwardness to achieve some kind of grace. Child is funny and self-deprecating, and (all respect to Gilbert) you don’t have to wade through her thoughts on meditation.

Calling this a travel book, or even more snubbily calling it a sports book, belittles the grace that William Finnegan weaves into the story of his lifelong love of surfing and the way it took him around the world. He captures the angsty drive to keep moving that fuels a lot of young travelers, the FOMO-y obsession of following something ephemeral, and the heartbreak of finding the perfect untouched place—in Finnegan’s case, Tavarua—and then having it changed by the next crew of travelers looking for the exact same thing.

Rebecca Solnit is a master of juxtaposing seemingly disparate ideas, digging into them, and then weaving them together in a way you may never have expected. A Field Guide to Getting Lost, her collection of essays about place, the unknown, and all the different ways one might get lost, is a mesh of stories that also manage to touch on travel, history, wilderness, and more. Plus, Beyoncé allegedly named her kid Blue because of one of the pieces, so you know it’s good.

You May Also Like

Block Breaker: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering the Game

March 22, 2025

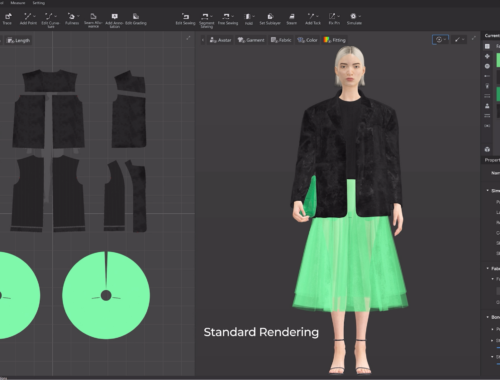

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025