Russia’s stability in flux?

Russia’s stability in flux?

Russia’s presidential election may prove messy for Russia but unusually quiet for the EU.

Vladimir Putin has not been a frequent visitor to Brussels. In almost 12 years as Russia’s prime minister, president and (again) prime minister, he has visited the EU’s ‘capital’ three times. Nor is the Russian leadership particularly enthusiastic about the EU. A WikiLeaks cable suggested that the Russians treat the European Commission’s president “harshly and condescendingly” as “basically a glorified international civil servant”. Russia, which has a preference for ‘divide and rule’, is uncomfortable with the EU trying to foster a unity of purpose among its member states.

Putin and the 11 Russian ministers visiting Brussels today will no doubt depart unenthused. This ‘executive to executive’ meeting with the Commission is a largely technocratic gathering, continuing the desultory search for a successor to the partnership and co-operation agreement that officially expired in 2007 but persists until replaced. Russia will bang the drum again for visa-free travel to Europe for Russians and express alarm that the EU’s third energy package hurts Gazprom, but nothing suggests this will result in a step-change on either issue.

The lack of novelty on the agenda suggests an answer to a broader question – how much prospect there is of fresh impetus in EU-Russia relations.

Over the past 20 years, Europe has demonstrated repeatedly that it is willing (too willing, many would say) to make concessions to Russia when it sees political opportunities and dangers. But when it is not clear what political opportunities and dangers there are, there is little reason to stray from a technocratic script.

That is the situation now. Such inflexibility on the EU’s part might vex Moscow, but it could instead choose to see this attitude as a badge of success – a sign that Russia is stable and the EU-Russia relationship has stabilised.

For the EU, the concern should be the downsides of Russia’s version of stability. The Kremlin shows them often. Most recently, while others were condemning the indiscriminate killing in Libya on Tuesday (22 February), President Dmitry Medvedev chose instead to fulminate that there will be “fires for decades” in the Middle East. No such scenario would be allowed in Russia, he said – and few doubt that.

A day earlier (21 February), Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, had pinpointed two sources of danger in this stability: Russia’s “imitation” of democracy, and the “incredible conceit” of Putin and Medvedev in saying that they would decide who the next president should be.

But Medvedev’s re-election or Putin’s restoration is unlikely to be as neat as their “conceit” might suggest. In the past week alone, we have seen many indications that Russia’s elite will be in ferment through to the March 2012 elections:

The country’s richest woman, Yelena Buturina, is now under investigation. (What does this mean for her husband, Yury Luzhkov, whose bid for the presidency was shot down early in the 2000 campaign and who was fired as Moscow’s mayor by Medvedev last year?) Aleksandr Lebedev, an oligarch, is refusing to travel outside Russia for fear of finding himself exiled. (Who, oligarchs wonder, will be targeted in the campaign?) Aleksei Kudrin, the finance minister, has attacked the lawlessness of Russia’s political and economic culture. (Are there reformers willing to fight?)

Click Here: cheap Cowboys jersey

Still, while such Kremlinology suggests a febrile 12 months in Russia, it is unclear whether it will produce risks and opportunities for Europe. At the moment, there seems less at stake than in previous elections.

At this point in the 2000 electoral cycle, all eyes were on the battle to succeed Boris Yeltsin. Which power group would triumph? How would the next president seek to establish stability in a reeling country?

For a time in the 2004 campaign, the question was whether the oligarchs created by the wild privatisation of the 1990s might do what the 19th-century ‘robber barons’ of the US had done: after making their money, would they seek to safeguard their wealth by trying to make Russia a less lawless society? Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Russia’s richest man, seemed to have chosen that option. He was arrested.

A year ahead of the 2008 elections, the questions were whether Putin would seek an unconstitutional third term and, if not, whether he would back Medvedev, his mild-mannered former chief of staff, or Sergei Ivanov and the strong men behind him. And would Putin’s choice remain docile?

The most important question so far in this cycle – whether either Medvedev or Putin will embrace reform – is no threat and, at best, a very forlorn hope.

At times, Medvedev has shown an appetite for reform, offering sharp critiques of Russia’s (ie, Putin’s) system. In essence, he has put himself into the odd position of being the president who called the emperor naked. But, after three years in office, it is hard to argue that Medvedev has the ability to reform the emperor’s system.

So far, then, the overarching political narrative of the 2012 campaign seems likely to be highly familiar – that Russia is returning to the 1980s, the Soviet period of zastoi, or ‘stagnation’. Europe knows some of the immediate implications, because Russia is already an unhappy place for awkwardly minded Russians and for foreign businessmen. In the unrest in the Middle East, it should already see some of the possible, albeit distant, consequences.

Fair access to all areas?

You May Also Like

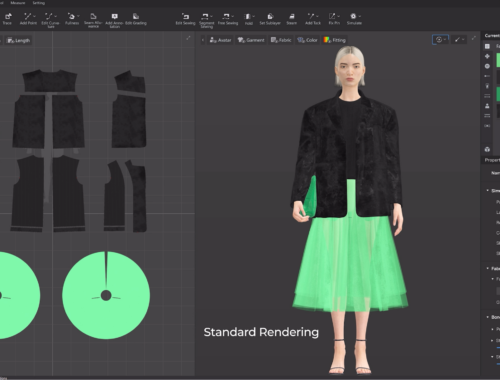

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

February 28, 2025

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability

February 28, 2025