Race Week Anxiety? You’re Not Alone

As Boston looms, so do the fears that haunt every marathoner

The Boston Marathon is less than one week away. Presumably, most of the 30,000 runners who will be taking the bus to Hopkinton on Patriots’ Day have already eased into late-taper, cruise-control mode. The hard work of marathon training is over. Only the small matter of racing 26.2 miles remains. It’s time to bust out distance running’s favorite cliché: “The hay’s already in the barn.”

That line never really did it for me. I think it’s because I tend to fall into the trap of indulging in what I call taper week “What If?” Syndrome—that is, the gloomy habit of envisioning hypothetical scenarios of all that might still go wrong. The hay may be in the barn, but what if the barn is struck by lightning and catches fire?

Sound familiar? In the spirit of allaying one’s fears by confronting them head-on, here are a few textbook symptoms of race week anxiety.

What If I’m Really Undertrained?

Another ubiquitous thing you might hear during race week is that you should “trust in your training” or, more pretentiously, “trust the process.” The obvious caveat here is that, as a means of reassurance, the mantra only works if your training has actually been good. What if your training has been a colossal shitshow? Alternatively, what if, a week before race day, you find out that the person you were hoping to use as a pacer has secretly been logging 30 miles more per week than you? Remember that sinking feeling you had in high school when, minutes prior to an exam, one of your peers asks about some theorem and you realize you have no idea what the hell they’re talking about? This is like that, only feigning sickness won’t help. Luckily, Outside has a handy guide for surviving a marathon that you haven’t really prepared for.

What If I Get the Flu?

Speaking of feigning sickness, taper week is prime time for runner hypochondria. One becomes increasingly paranoid that months of training will go to waste because of untimely illness or injury. A minor hamstring ache that you wouldn’t have noticed a few months ago suddenly augurs calamity. Ditto that scratchy throat. You become so wary of enclosed crowded spaces that you consider investing in one of those masks that Michael Jackson used to wear. You discover there’s no subtle way to quarantine yourself from your significant other who has a minor cold.

What If My Stomach Betrays Me?

Fueling plays a big role when it comes to marathon preparation, so it’s only to be expected that the subject would also be relevant to race week jitters. To make matters worse, prospective food woes can come from multiple fronts. On the one hand, there’s the threat of conventional food poisoning: a ceremonious pre-race dinner of coq au vin seems like a prudent choice until you feel the rumblings of salmonella. Then there are food issues that can occur midcourse: It’s difficult to be 100 percent confident about how your body is going to react when you guzzle a caffeine-infused gel after cresting Heartbreak Hill. One encouraging thing to remember here, however, is that there have been some memorable performances in which runners experienced on-course stomach issues and still went on to glory. Two favorite examples: Paula Radcliffe in 2005 demonstrating that Porta-Potties are for suckers, and Bob Kempainen projectile vomiting at mile 22 of the 1996 Olympic Marathon Trials while hardly breaking his stride.

What If I Have to Race in Awful Conditions?

Telling someone not to worry about what they can’t control is sound, rational advice. It’s also a completely useless thing to say to a marathoner when it comes to fretting about race day weather—particularly for an event like Boston, where it can snow or hit the mid-80s. In the past, I’ve told myself that I wouldn’t look up morning-of conditions until two days out for maximum accuracy, only to ultimately end up consulting multiple ten-day forecasts on different websites. In my defense, the case can be made that the amateur runner has more cause to worry about weather than the professional: Generally speaking, pros compete for place, whereas non-pros are in it for time. When your main objective is to beat those around you, that race day scorcher can potentially be an advantage. When your goal is to PR, not so much.

The Remedy

If all else fails, the best cure for race week What If? Syndrome is simply to take a big-picture approach. Remind yourself that whether you fail or succeed on race day is not going to matter much in a few billion years when the sun expands enough to vaporize our planet. It’s advisable, however, to forget about this if you wind up having the race of your life.

You May Also Like

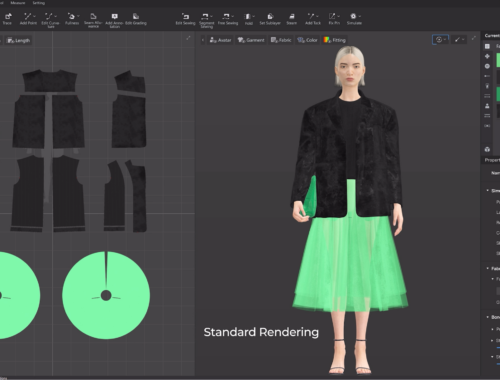

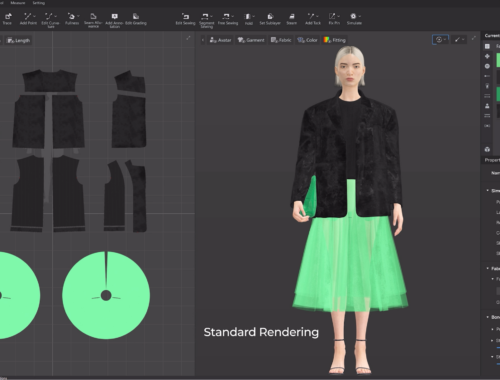

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

トレーラーハウスで叶える自由なライフスタイル

March 17, 2025