Putting Napping to the Test

It feels good, but does it boost performance? Only randomized controlled trials can tell us.

I’m currently reading a great book about randomized trials, which is honestly more interesting than it sounds. Randomistas: How Radical Researchers Are Changing Our World is by an Australian economist-turned-politician named Andrew Leigh, and its fundamental premise is that we don’t really know anything until we test it properly with a randomized trial. Give some people the treatment; withhold it from others; see who fares best.

The book starts with James Lind’s famous 1747 experiment that assigned 12 scurvy-ridden sailors to receive cider, sulfuric acid, vinegar, seawater, a paste of spices, or citrus fruit, which is often pegged as the world’s first randomized trial. (How bad was scurvy? During the Seven Years’ War, from 1756 to 1763, Leigh reports, “Britain raised 185,899 sailors; only 1,512 died in action, while 133,708 died of scurvy.”) But the book doesn’t stick to medicine; it surveys the far-reaching power of randomized trials in education, poverty reduction, economics, and other areas. The overall theme: sometimes our instincts are right, sometimes they’re wrong.

This message was echoing in my mind when I saw a new randomized trial in the European Journal of Sports Science, from a team led by Anthony Blanchfield of Bangor University’s Extremes Research Group, called “The influence of an afternoon nap on the endurance performance of trained runners.” On the surface, it’s obvious: a nap is a wonderful thing, so of course it should boost your performance! But the findings are a little more complicated.

The study involved 11 runners who visited the lab twice for time-to-exhaustion tests in random order. Once they were instructed to take a 40-minute nap about 90 minutes before the test; once they weren’t. At first glance, the nap (which included about 20 minutes of actual sleep time on average) didn’t seem to make any difference: the average times were 596 seconds with the nap versus 589 seconds without, which was nowhere close to a statistically significant difference.

But there was an interesting pattern. Those who had slept the least the night before were more likely to see an improvement in their time. Here’s what the individual results looked like as a function of night-before sleep time (with numbers above zero indicating a post-nap improvement):

This looks awfully suggestive. In fact, the runners who improved their time trial after the nap had an average of 6.4 hours of night sleep, while those who didn’t improve had an average of 7.5 hours. And these sleep durations were consistent with a night of sleep testing that the subjects did a month before the experiment, suggesting that it’s the overall pattern of sleep, rather than a single night of poor sleep, that made the difference. The authors conclude that “a short afternoon nap improves endurance performance in runners that obtain less than 7 [hours] night-time sleep.”

All of this makes intuitive sense—which, thanks to Leigh’s book, sets off some alarm bells in my head. After all, wouldn’t it be equally valid to conclude that “a short afternoon nap worsens endurance performance in runners that obtain more than 7 [hours] night-time sleep?” Since there was no difference between the nap and no-nap conditions overall, improvement in some subjects has to be balanced by worse performance in others.

In fact, when I looked up some other papers to see what they’d found, I noticed a brand-new one in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance which found that an afternoon nap had no effect on target-shooting performance and worsened 20-meter sprint performance in high-school athletes in Singapore. There may be a difference in how naps affect sprint versus endurance performances; or it may be that the athletes in the Singapore study were still suffering from sleep inertia, since they had to sprint just 45 minutes after waking up. But apparently a nap isn’t always a good thing.

Personally, my instinctive belief in the power of naps is so strong that I can’t help but be convinced by the figure above: naps must be performance-enhancing if you’re sleep-deprived. But that’s the sort of thinking that, in countless examples in Leigh’s book, leads policy-makers to ignore the findings of randomized trials. Scurvy’s horrific death toll in the Seven Years’ War, you’ll note, came more than a decade after Lind had shown that citrus fruit could ward off the disease. So I’ll try to keep my mind open until newer, more robust evidence becomes available. In the meantime, I’ll keep napping whenever I get the chance—not in the expectation of a performance boost, but simply because I love the feeling of falling asleep on the couch on a sunny afternoon with a book on my chest. On this topic, maybe’s that’s all I really need to know.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.

You May Also Like

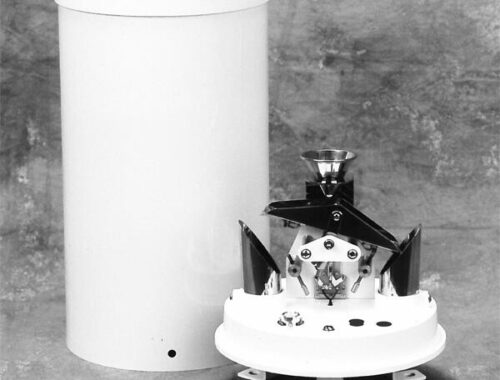

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025

シャーシ設計の最適化手法とその応用

March 20, 2025