Op-Ed: Chris Froome Should Not Ride the Giro d’Italia

Amid an ongoing doping scandal, the Sky racer is within his rights to continue racing. He shouldn’t be.

Once again professional cycling is setting itself up for a self-inflicted, scandal-driven mess. Next week, Chris Froome, who stood atop the podium of both the Vuelta a España and the Tour de France in 2017, will line up at the Giro d’Italia to take aim at the one Grand Tour victory that has eluded him. In a doping-free world, the pre-race hype would be focused on whether the Brit will become the seventh racer in history to win all three Grand Tours. Instead, the speculation revolves around whether he’ll become the first rider since Alberto Contador to be stripped of a Grand Tour title.

Froome begins the Giro under a blanket of suspicion over his unresolved salbutamol case, which dates back to last year’s Vuelta. Froome’s urine sample following Stage 18 of that race indicated more than the permissible amount of salbutamol—a bronchodilator used to treat asthma. While the drug isn’t banned for use by pro racers and does not require a therapeutic-use exemption, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) sets a threshold for its presence in a urine sample. Froome’s sample came in at twice the allowed concentration. Experts have said that it’s unlikely that Froome could have registered such a high amount while staying inside the restrictions for the drug. Meanwhile, Froome and Team Sky have denied any wrongdoing, claiming that the high test value is due to doctor-recommended usage of the drug. They are challenging the results.

So Froome lines up next week in hopes of conquering the first Grand Tour of 2018 even as it’s still unclear whether he legitimately won his last Grand Tour race.

According to the rules, Froome has every right to race. Because salbutamol is a “specified substance” under the WADA code, his Vuelta result doesn’t trigger a racing ban. Instead, Froome has the right to exonerate himself by providing documentation and a medical explanation for the failed test—and to keep on racing until a decision is reached. That saga will play out in the courts, according to what UCI president David Lappartient has called a complex procedure. “He has more resources than the others and has good lawyers, like we do,” Lappartient told the French newspaper L’Equipe. “Because he argues that he has followed the rules, that has made the investigation a lot bigger.” Initially, there was some hope that the dispute would be resolved ahead of the Giro, but the intricacies of the case and the legal wrangling have prevented that.

The rules permit Froome to race, but they shouldn't. It’s impossible to argue that his participation will tarnish professional cycling’s reputation—which, following decades of scandals, is about as credible as the WWE—but participation makes a mockery of the rules and the race.

Allowing him to ride is like finding evidence that suggests your bookkeeper stealing from you, demanding an explanation, then giving him as much time as he needs to come up with one while still allowing him access to your accounts. The other racers can have no confidence in their chances given that Froome exceeded the legal limit for a performance enhancer in a previous race and could still be upheld as its winner. If I were 2017 Giro champ Tom Dumoulin or any of the other big contenders, that question mark over equality would make the whole endeavor an exercise in futility.

Imagine how pointless it would be if Froome wins the race, then loses his salbutamol defense. That loss would likely lead to a suspension; in two similar salbutamol cases, Diego Ulissi was handed a nine-month layoff and Alessandro Petacchi received a one-year ban. More important, it would negate Froome’s 2017 Vuelta victory and probably his Giro results, too—even his 2018 Tour results, if the case drags on into the summer. In 2011, Alberto Contador won the Giro while his case over a failed clenbuterol test during the 2010 Tour de France was pending. When the case was decided against him that February, Contador was stripped of his Giro title. In other words, not only do WADA’s rules lead to the absurd situation of a race’s results being revised in the absence of a specific offense—Contador still maintains that he is the rightful victor of the 2011 Giro, since he passed all drug controls while riding it—but it also steals the podium experience from those who’ve truly earned it. When the Giro results were revised in 2012, no one cared that Michele Scarponi became the champ on paper, nor did his team reap the financial and PR benefits.

The scenarios described above involve a lot of what-ifs, and it’s unlikely that all of them will come to pass. However, that they’re even possible underscores just how big a farce pro cycling has become. Why should fans care about the sport if the results of the three biggest races of the season could be in question?

One way to prevent future situations like this would be for the UCI to change its rules to immediately eliminate from competition any rider who tests outside the regulations until the matter is resolved. Doing so would help bolster the sport’s credibility; after all, doesn’t it make sense that if you break the rules—or at least if it seems like you broke the rules—you don’t get to race? Mandatory suspension would also speed up doping proceedings, since racers, teams, and governing bodies would all have a vested interest in reaching a swift conclusion. Of course, there’s been no serious discussion of any rule changes. And if cycling history tells us anything, it’s that there's unlikely to be a permanent fix.

You May Also Like

China’s Leading Pool Supplies Manufacturer and Exporter

March 18, 2025

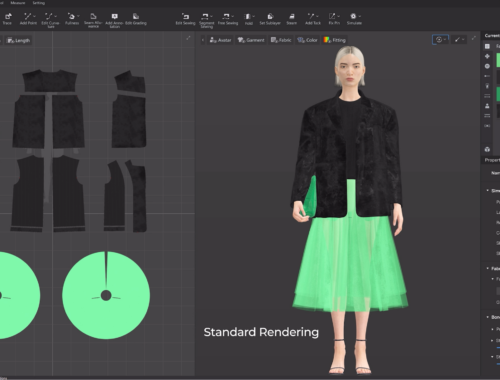

AI in Fashion: Transforming Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for the Future

March 1, 2025