One success doesn’t solve Belgium’s failures

The coincidence was striking, almost sinister.

On the east side of Brussels, the European Council was drawing to a close, with what Donald Tusk, the European Council president, called an “historic” agreement with Turkey. Meanwhile, on the west side of Brussels, in the now notorious suburb of Molenbeek, Belgian security services were closing in on Europe’s most wanted man, Salah Abdeslam.

On the face of it, these were two very separate incidents, connected only by a simple accident of timing, but they did not stay separate for long.

Ahmet Davutoğlu, the Turkish prime minister, chose, very deliberately, to repeat the criticism of Belgium voiced by his president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, earlier in the day for allowing street demonstrations outside the European Council in support of Kurdish separatists.

At the very moment that Belgium was scoring an apparent victory in its fight against terrorism, Davutoğlu berated Belgium for its tolerance of terrorism — equating those who demonstrate in support of the Kurdish cause in Brussels with those who set off bombs in Ankara.

“Terrorism is a threat to all of us,” Davutoğlu said. “Two capitals in Europe have been targeted by terrorist organizations, Paris and Ankara, twice. And both times, in Paris and Ankara, we stood shoulder to shoulder and this solidarity against terror — regardless the origin of terror, Daesh, PKK or DHKP-C, regardless of the terrorist organization — that’s what we need.”

By the time Davutoğlu made these remarks — much to the discomfort of those on the stage with him, Tusk and Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission — Charles Michel, the prime minister of Belgium, had already rushed from the European Council building to follow events as they unfolded in Molenbeek.

But earlier in the day Michel had responded to Erdoğan’s comments with a message on Twitter: “Freedom of speech and expression are essential to democracies. Belgium is committed to defend these values at home and abroad #Turkey #EUCO.”

No expertise in the compressed language of Twitter is needed to see that Michel believes freedom of speech and expression are under threat — in need of defense — in Turkey. And he is right. Earlier this month, the Turkish government took control of the main opposition newspaper, Zaman, only the latest in a series of repressive acts.

And that is why, while Belgium and Turkey trade diplomatic blows, the European Union’s leadership squirms.

The dilemma for the EU is that it needs the cooperation of Turkey if it is to reduce the flow of migrants into the Balkans, but the solution that it has devised — returning people to Turkey — depends on Turkey being recognized as a fit and proper place to which to send people back; in other words one which respects the rule of law, freedom of speech, and human rights.

There are various points of contention in the agreement reached between the EU and Turkey (such as the ability of the authorities in Greece to process the registration of migrants, and the premise that this will “break the business model of the human traffickers”), but the point that the EU is arguably least able to control is the Turkish government’s repressive tendencies.

And yet the EU’s discomfort with Turkey is mirrored, on the other side, by discomfort with Belgium. That Abdeslam has been captured does not, at a stroke, end all doubts about Belgium and why it has proved such a hot-bed for radicalism.

Reputational damage

The attacks in Paris in November provoked trenchant criticism from various quarters, including from this website, of how Belgium had failed in its duty to keep public order. It takes much more than the arrest of the Bataclan perpetrators to address all those problems: the failure to confront radical mosques; the availability of weapons and false documents; the poor coordination between the various layers of law-enforcement and the poor quality of some community policing.

Davutoğlu was wrong to imply that only Ankara and Paris had been affected by terrorism — forgetting the 2014 shooting at the Jewish museum in Brussels — but such suffering does not diminish Belgium’s failures.

Belgium’s international reputation took a severe knock in November in the aftermath of the Paris attacks. How much it recovers will depend a lot on the details that emerge over the coming days and weeks about the Belgian investigation that led to Abdeslam’s arrest.

If, as currently seems plausible, the police owe his capture to a lucky break — a fortuitous discovery on Tuesday, when police checked out what they thought was an empty safe house — then they may not get much credit. Especially if it emerges that he was in Brussels all this time. Rather, the question that will be asked repeatedly is “why did it take so long?”

Such questions will feed criticism that Belgium has been a soft touch, that it has not done enough to confront radicalism. And successful counter-terrorism operations this week will not automatically dispel the impressions that the causes of terrorism have not been addressed.

Click Here: Maori All Blacks Store

The other government leaders around the European Council table with Michel know that in a globalized world the threat of terrorism has become so prevalent that European societies cannot be as liberal as they once were. There are uncomfortable choices to be made: ensuring public safety apparently necessitates greater public surveillance, more infringements on public liberty, and less respect for the niceties of procedure.

Where then should the balance be struck? European leaders have been anxious this week to make clear their values must be defended, that they will not go down the path of repression taken by Turkey. But copying Belgium is not the answer either.

Tim King writes POLITICO‘s Brussels Sketch.

You May Also Like

ユニットハウスのメリットとデメリットを徹底解説

March 20, 2025

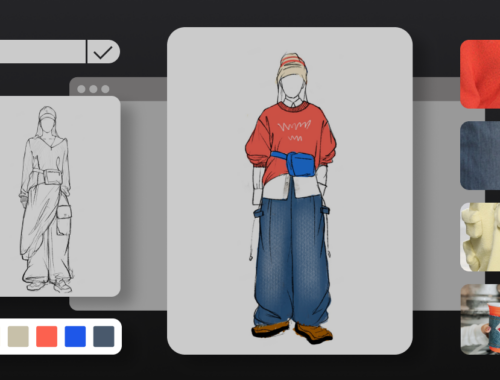

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025