On Thin Ice in Ouray

>

Take a walk down Main Street in Ouray, Colorado, on a winter day and you’ll see throngs of pedestrians in bright, technical outerwear—some wearing backpacks, helmets, and harnesses—and a steady stream of cars heading to the Uncompaghre Gorge above town, home of the Ouray Ice Park. You could mistake yourself for being in the Alps. Coffee shops, breweries, and restaurants that previously shuttered through winter now have the lights on and “Please Remove Crampons Before Entering” signs on their doors. This wasn’t always the case.

Prior to the ice park’s official opening in 1997, the historic mining town, population 1,000, hibernated through winter. Businesses would close, waiting for the peak tourist season of summer. Main Street was a ghost town. The steady growth of visiting ice climbers over the years, along with Ouray’s internationally-renowned annual ice festival—which attracts upwards of 3,000 climbers for a single weekend—has kept Ouray alive through the cold months.

Yet in this seemingly utopian mountain town, a streak of short and challenging winters combined with growing overcrowding issues and a management dustup has given rise to a new anxiety: How can a small rural town make outdoor recreation both environmentally and economically sustainable in a rapidly changing West?

For the park to open each winter, the ice farmers—a four-member team that manages a complex irrigation system of 7,500 feet of pipe and 250 showerheads and drains that run water down the 45- to 150-foot-tall cliffs—typically need a month and a half of lead time from the first frost. But the ideal temperatures for ice farming—26 degrees or lower at night—are arriving later and later. As a result, the farmers have less time to build a big enough ice base to make it through warm spells in January and February.

“We start running water in the beginning of November,” says Dan Chehayl, executive director of Ouray Ice Park Inc. (OIPI), the non-profit that runs the facility. Historically, the park would open around the second week of December and continue until the end of March. A typical season lasted 90 to 100 days. The winter of 2013–14 was a banner year at 108 days. But ever since then, the season has shrunk, with 2016–17 lasting just 46 days.

Even when it’s cold enough, the park doesn’t always have the water to sustain full operations. The farmers need 150,000 to 300,000 gallons every night to repair the damage done by climbers swinging ice tools and kicking crampons during the day. That water is the overflow from the city’s spring-fed storage tanks above town. In recent years, however, the volume has diminished significantly thanks to the drier winters, mining diversion, increased demand from the growing city, and an aging infrastructure. “There were leaks that got bigger and bigger until they were basically the size of all the water allotment we needed,” Chehayl says. (After last year’s early closure, the city fixed the major leaks in their infrastructure over the summer. This year, the ice park opened on December 23, delayed by warm temperatures, but they remained open until April 1, a date they haven’t reached since the water issues began in 2014, for a 100-day season.)

Chehayl and park staff work with the water they have or shut off the park’s pipes altogether. To cut their losses, they’ve already closed three areas that weren’t worth their diminishing resources. They dropped from a peak of around 200 routes within a one-mile stretch of the Uncompaghre Gorge to approximately 150 routes after the 2013–14 season.

Despite the uncertainty of park conditions in recent years, annual visitors are steadily on the rise and overcrowding is becoming a new headache. OIPI is playing with the idea of a visitor cap. The problem is, staff have no visitation data beyond an educated guess. The park is free, there are multiple entrances, and people come and go throughout the day, so it’s difficult to get an accurate count. Chehayl estimates around 14,000 visitors a season.

OIPI currently runs the ice park on a thin budget of donations, memberships, and sponsorships from the ice festival. “We’re slowly understanding that it’s going to require revenue streams to protect and defend certain portions of our sport,” says Luis Benitez, director of the Office of Outdoor Recreation Industry in Colorado. But, he says, “The question of who pays for what when it comes to conservation and stewardship will always be a challenge in small, rural communities.”

In the world of outdoor recreation, the ice park and the city of Ouray have a unique, symbiotic relationship. Nowhere else is a local municipality and climbing organization so intertwined or dependent on one another. The city owns the water needed to farm ice and the majority of the land that encompasses the ice park. OIPI, contracted by the city to operate the park, keeps alive the core of Ouray’s winter economy and attracts new residents to the area.

This relationship, however, is becoming increasingly strained. OIPI’s current five-year contract with the city ends in May. The park’s board of directors previously considered handing over the management of the park to the city, but ultimately decided against it. Ouray and OIPI are in talks for a new contract. “There’s a lot of things that we want, and there’s a lot of things that the city wants—so all getting on the same page has been a rough go,” Chehayl says.

The future direction of the Ouray Ice Park, and therefore Ouray’s outdoor-recreation-based economy, depends largely on the new agreement between the city and OIPI. Both parties are hopeful that they’ll see a contract signed by the end of May, if not earlier.

In the next five years, Chehayl hopes to see the park grow from “more of a cowboy-run operation to a really well-oiled machine,” with a fulltime staff and reliable fundraising, all to help better weather the changing times.

Whatever Ouray decides, it will set the precedent on how a whole community—outdoor recreationalists, guides, business and land owners, local government—can, and should, all come together to create a long-term, sustainable plan around outdoor recreation. If other outdoor industry leaders are not watching Ouray, they should be—the city is navigating uncharted waters.

“Ouray is setting an example for everyone,” says Benitez. “The outdoor industry is starting to wake up to the fact that conservation and stewardship are deeply connected to how effective we are as an economy.”

You May Also Like

コンテナハウスの魅力と活用方法

March 14, 2025

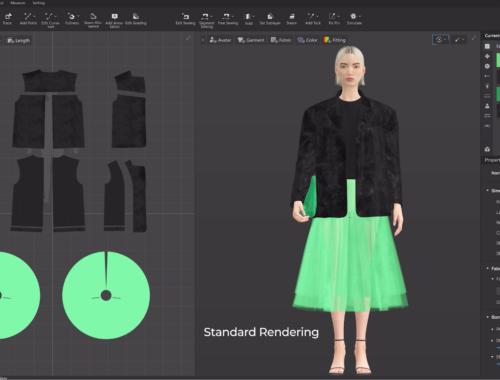

**AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability**

February 28, 2025