National Parks Fee Increase Would Cost Local Towns

>

In October, the Department of the Interior proposed an entrance fee hike that would roughly double the cost to visit 17 of the country’s most popular national parks. The National Park Service carries a $12 billion budget shortage, leaving it without funds to repair things like roads, buildings, and restrooms. The rate increase was pitched as a way to fill the gap. “Targeted fee increases at some of our most-visited parks will help ensure that they are protected and preserved in perpetuity,” Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke said at the time.

The proposal ignored a lot of other factors, like the Trump administration’s simultaneous plan to cut $400 million from the Park Service budget. It also ignored the possible repercussions on surrounding towns. A new study from the University of Montana, however, focuses on just that. Looking at just Yellowstone National Park, the study found that Zinke’s increase would cost towns within a 60-mile radius of Yellowstone about $3.4 million each year. And this prediction accounts for only the price increase on seven-day passes, which is just 30 percent of visitors, says Jeremy Sage, associate director of the university’s Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research. The overall impact is likely much greater.

“It’s not surprising, really,” Sage says. “Think about any good or service: When the price goes up, the demand for it goes down. Entry into the park and spending in neighboring communities is a complementary good—if peanut butter prices go up, demand for jelly goes down.”

The proposed park fees would increase during peak visiting season—June to October—and would raise vehicle passes to about $70, motorcycle passes to $50, and hiker and cyclist passes to $30. As a comparison, at Grand Canyon last year, those fees were $30, $25, and $15, respectively. Park fees have been rising in recent years, so in a sense this is continuing a trend. Campgrounds and parks across the country have increased fees on everything from senior citizen passes to picnicking. National parks are also increasingly more popular and crowded. Last year, a record 331 million people visited the parks, and with the lines and crowds, there’s a real demand to limit traffic.

In a way, the fee hike acts like surge pricing for Lyft and Uber. It deters some while charging a premium for those who can afford it, which in turn helps the budget shortfall. The question raised by the University of Montana’s study, however, is what’s the smartest way to do this?

The researchers knew that when travel becomes more expensive, fewer people visit parks; for every 10 percent increase in travel costs, park visits decline by about 3 percent. That figure may change a little depending on the type of visitor. While people who live in Montana may pay about $100 to visit Yellowstone, an international traveler is paying thousands of dollars, so a park fee increase doesn’t factor into the travel budget the same way. But nearly 80 percent of the people who visit Yellowstone are Americans from at least one state away, and the entry fee hike has a real impact on them.

For these people, Zinke’s proposed entrance fee hike adds about 14 percent to travel costs, which means tens of thousands of Americans will decide not to visit Yellowstone, according to the study. That adds up to millions of lost dollars for surrounding towns. And that’s only for people unwilling to pay the higher price for the seven-day pass. A lot of other fees could be raised, too. If you use this same arithmetic for the 16 other parks—including Arches, Joshua Tree, Yosemite, and Zion National Parks—you get an idea of what Zinke’s proposal might do across the United States. It’s no small matter, because money from parks visitors create 318,000 jobs in local U.S. communities.

What’s more, Zinke’s pay structure will hit low-income families the hardest. That’s raised a lot of complaints about access. There’s also a lot of anger and confusion over why other options weren’t explored. For example, to visit Kilimanjaro National Park, in Tanzania, the government charges foreigners $70 per person per day. Locals get in for $4.45. A fee structure like this, according to the study, also makes more sense because adding $40 or more onto an international plane ticket doesn’t affect the overall cost that much, and research proves these visitors will still make the trip. “We’re not saying this is what you should absolutely do,” Sage says, “but take a look at other options.”

This gets at what most concerns Sage: He worries that Zinke’s department hasn’t done much research. The Department of the Interior figures the added fees will increase the Park Service’s budget by 34 percent next year. But that doesn’t seem to account for the loss in visitors or a number of other factors. When Sage’s department asked Zinke’s office for its research, he never heard back. “I haven’t seen any evidence to suggest they’ve done a good enough job of exploring other options.”

Nike Announces Epic React Flyknit

You May Also Like

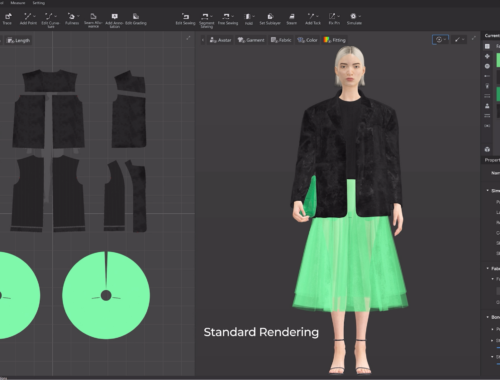

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025

Automatic Weather Station: An Overview of Its Functionality and Applications

March 14, 2025