My Wildly Fun Test Drive of a Seabreacher Submersible

>

The first time you see the Seabreacher tearing through the water, a visceral feeling of What the hell is that? sweeps through your body. It looks like an extra-large turbo-powered mechanized dolphin. It can dive below the surface, leap into the air, and travel at speeds in excess of 60 miles per hour. You feel like you’re looking at a previously undiscovered apex predator—one that’s 16 feet long, weighs 1,500 pounds, and is made of metal—and you kinda want to run away screaming.

But holy crap, is it fun to drive.

Over the summer, I traveled to Lake Shasta in Northern California to check out the latest and greatest from Innespace, the company behind the Seabreacher, and get some cockpit time. The brand has been around for more than a decade, but the construction and performance of its Megazord-like watercrafts have evolved. The base model is the Seabreacher X. It borrows a 240-horsepower engine (and other components, such as the throttle and shifter) from a Sea-Doo jet ski. It has a fixed snorkel, which allows the engine (and you) to continue to breathe even when you’re speeding under the surface. Then there’s the Seabreacher Z, which is the high-performance model. It packs in a 300-horsepower motor and has a retractable snorkel, so not only can it dive and jump like the X, it can also do barrel rolls.

The company has outfitted Seabreachers to look like sharks, sailfish, dolphins, orcas, eagles, and even manatees, as well as fighter jets. Every boat is a commissioned custom job. I got to test-drive the company’s latest creation: a Seabreacher Z modeled after a certain Italian supercar. It’s called—wait for it—the Searrari.

Each Seabreacher has two seats, with the driver in front and the passenger in back. The vessel is pretty narrow, so I had to climb into it like I was getting into a kayak, stepping directly into the center of the craft and being conscious of my balance. I sat down on the leather seat, latched the buckle on the four-point racing seatbelt, and was ready to go. Rob Innes, the Kiwi who invented these things, sat behind me as my instructor, shouting directions over the roar of the engine.

While you can drive with the hatch open, if you’re going to be going fast or diving at all, you pull the clear hatch down over the cockpit, latch it on both sides, and then press a button that inflates a seal (borrowed from the aerospace industry) to 20 psi, effectively making the vessel watertight. I wanted to close the hatch as quickly as possible, because, as a beginner, I knew that in one false move I could flood the whole cockpit in a matter of seconds.

Driving the thing definitely takes some getting used to. It’s not like a car or even a jet ski or a plane. Turning (yawing) is controlled by your foot pedals. I pushed down with my whole right foot to turn right and my left foot to go left. Easy, no? Well, I also had to use my feet to control the pitch. When I wanted to tilt the nose down and dive, I pressed the pedals with just my toes. To get the nose high, I stomped just my heels. It’s a bit tricky to master. The throttle was a trigger on the right-hand control stick. And speaking of the sticks, they control the roll.

By far the coolest thing to do in the Seabreacher is diving. You need to get up to about five or seven miles per hour, or you won’t have enough momentum to counter your buoyancy. I was told to go toes back to lift the nose, and then slam them all the way down, hard. The moment the nose dipped below the surface, I went full throttle, hands and toes all the way forward. The cockpit window was engulfed in a world of green, the engine was roaring, my ears were popping, and then I slammed my heels down and the vessel went flying into the air, landing in a spectacular, tooth-rattling belly flop. It’s a serious thrill. How long you spend under the surface is really up to you. You could do a quarter mile easily if you got the angle just right.

“When you’re in a dive and you feel like you’re going too deep, your instinct will be to pull back on the hand sticks,” Innes told me. “Don’t do it. It’ll just stall out, and you’ll pop back up backward. Every time you do that, you owe me ten bucks. People usually owe me $100 by the end of a one-hour lesson.” Luckily, I only had to hand him a twenty after my day on the lake.

There’s something about being underwater while going fast that just feels wrong. And dangerous. A water droplet or two would make its way in, and I’d get nervous. I had the tendency to go too deep, which would choke the engine and cause me to lose power. Other times I wouldn’t go quite deep enough, so when I popped back out it was more of a little hop rather than a serious jump. And yet these things are extremely buoyant, as well as self-righting, and I knew I would always end up safe on the surface—at least in theory. There were times, though, when I was able to find that perfect balance point and go screaming long distances just under the surface of the water.

The Model Z was almost more vehicle than I could handle. You really feel that extra horsepower, and it’s not easy to tame. The controls were more sensitive, too. I found myself sliding out of some of my turns. This is also when I got to try barrel rolling, which is harder than it looks (and it doesn’t look easy). To do it, you have to be hydroplaning at about 20 to 25 miles per hour, toes pointed like crazy to keep from bouncing. (At that speed, there’s no breaking the surface tension of the water and diving.) Then, as hard and fast as you can, you throw the hand sticks in completely opposing directions—one forward, one back. It’s fast and violent, and it made my head bounce off the cockpit window. My tendency was to be a little too gentle, which stalled me out on my side after a three-quarter turn. I managed a one and a half before stalling out upside down. Not the slickest maneuver.

Experienced pilots like Innes are masterful when driving. They can do precise power slides, repeatedly dive below the surface and then spring into the air (a maneuver they call porpoising), and pull off high-flying tail taps and back flops. Riding in the passenger seat while they do this is very exciting, a little bit scary, and at times physically uncomfortable. Overall, though, it’s a blast, and I’d recommend the experience to anyone who isn’t claustrophobic or easily prone to motion sickness.

Seabreacher only makes about 20 boats a year, and every one of them is bespoke. As you might imagine, these toys cost a pretty penny. The entry-level Model X starts at about $80,000. The Model Z I tried went for $130,000. These are most definitely luxury items, and the interior reflects that, with the custom leather seats, a four-speaker marine-audio setup from Kicker, and a killer paint job. Why would you need one of these things? Well, despite them being fun as hell, you don’t. At least, you probably don’t need to own one yourself. That said, there are a growing number of places around the world where you can rent these things by the hour, take lessons, and give them a go without putting yourself into debt. If you can find one, you’ll be happy you went for it.

You May Also Like

HOW TO PREVENT MOLD AND MILDEW ON TRUCK TARPAULINS?

November 22, 2024

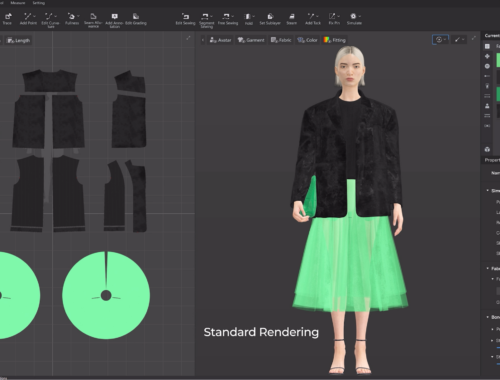

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025