Molly Huddle and the Perks of Running Dangerously

Sometimes a little bit of recklessness pays off

At last Sunday’s Aramco Houston Half Marathon, Molly Huddle ran 1:07:25—a new American record. In doing so, Huddle dethroned the illustrious Deena Kastor, whose mark of 1:07:34 stood since 2006. “I couldn’t dream of passing the torch to a more deserving athlete,” Kastor tweeted afterward, throwing in the #cleansport hashtag for good measure. For Huddle, who will be contesting her second marathon in Boston this spring, it was a hell of a way to kick off 2018.

Impressive as it was, one interesting aspect of Huddle’s race is that she slowed down considerably over the final miles. According to official results, her last 5K split (16:20) was more than half a minute behind her average for the first two (15:48 and 15:46, respectively). In a post-race interview, Huddle even acknowledged that she “blew up.” Blowing up, however, was apparently part of the plan. Given the strength of the elite field, her goal was to hold on for as long as she could, in the hope of coming away with a fast time. (Despite her record, Huddle finished seventh behind a bevy of East African talent. The winning time was 1:06:39.) “I knew the bottom would fall out eventually, but it was fun to see where the line was for me,” Huddle said in the interview.

Wait, what?

Running until the bottom falls out? Doesn’t that defy the golden rule that one should never go out too fast in a race? Generally speaking, running the opening miles hard in the hope of giving oneself a cushion for later in the race is a distance running no-no. The longer the race, the more the rule applies. I know a guy who works in the financial services industry but redeems himself through his enthusiasm for endurance sports. As he puts it: “The Bank of Marathon accepts no deposits—borrowings only. Whatever time you think you’re putting in the bank early is drawing against your later reserves and must be paid back with interest later in the race.” (And you probably thought banker bros were incapable of nifty metaphors.)

Did Molly Huddle just prove otherwise?

Probably not.

First off, it’s worth noting that Huddle wasn’t exactly staggering to the finish line in Houston. “Blowing up,” in other words, is relative. Huddle went from averaging a 5:05-minute mile early on to a 5:15 for the final three miles of a half marathon. While the early pace was ultimately too “hot” for her, Huddle wasn’t being totally reckless. She knew what she was doing.

“I’ve been in that position a couple of times in my career,” Huddle told me over the phone this week. “In some of the Diamond League track races, where I’m kind of in over my head and my PR might be the eighth or ninth fastest one in the field. Those days, you kind of just take advantage of being surrounded by those athletes who are better than you. You know you’re going to get pulled along for the majority of the race, and you just hope you can hold it together enough at the end so that when you fall off, you still run fast.”

It’s an approach that’s worked for her on the track. Huddle’s résumé includes an American record in the 10,000 meters (30:13.17), set at the Rio Olympics in a race where Ethiopian runner Almaz Ayana destroyed the world record. Similarly, when Huddle broke her own American record in the 5,000 in 2014 (14:42.64, since broken by Shannon Rowbury), it came in a stacked race in Monaco where she finished sixth. Those race experiences probably also made it easier for Huddle to go for it in Houston.

“I think what Molly did was that she took a calculated risk,” NAZ Elite coach Ben Rosario, who was on hand in Houston, told me. “It wasn’t so fast that you would call it irresponsible. Certainly, for someone of her caliber in the 10,000 meters, to do the kind of splits she was doing early on in the half wasn’t unchartered territory for her.”

As for “irresponsible” running, even top athletes are not immune. In 2015, in his final marathon as a professional, Ryan Hall went out at world record pace on an unseasonably hot day in Los Angeles. It didn’t end well. (And don’t get me started on those overzealous non-pros who like to hang with the world elites for the first mile or so of a major marathon just so they can be on TV. Granted, these runners are likely not gunning for a PR, but they personify the difference between taking a risk and just being stupid.)

In fairness to Hall, the physiological demands of the marathon make it a fundamentally different kind of race. In the shorter distances, it’s easier to be irresponsible and get away with it. In the marathon, on the other hand, when you blow up, you really blow up.

“There’s an added element in the marathon that’s not there in the half or the 5K, which is that you’ll run out of glycogen storage. Once you do that, no amount of willpower will get you to the finish line any faster,” says Rosario, whose stable of marathoners includes 2:12 guy Matt Llano, and Kellyn Taylor (2:28), among others. “If I were giving general advice across the board, I would say taking a calculated risk in the 5K or 10K or the half marathon is something that you might consider, but in the marathon you really have to know yourself and what you’re capable of and stick to the plan.”

For Huddle’s part, the newly crowned American record-holder in the half marathon agrees.

“I definitely wouldn’t do it in the marathon,” Huddle said when I asked her whether she would ever intentionally go out too fast in a 26.2-mile race. She will have to resist that temptation at the Boston Marathon in April, in a race that features arguably the strongest field of American women ever assembled.

“My racing style is just to kind of go with the front and see what happens. But I know that if you do that in a marathon, you might not finish, and that’s never been a fear for any of the other races I’ve done,” Huddle said. “Especially a course like Boston, I think that comes into play a lot. You see people who don’t even know that they went out too hard, and they end up coming back to you in the end. It’s definitely something I’ll keep in the back of my mind—that you really have to stay within yourself when it comes to that distance, because it’s not just you racing the girls ahead of you. It’s you racing the marathon.”

You May Also Like

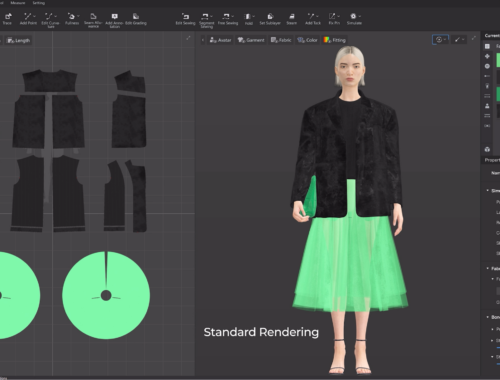

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for a Smarter Future

March 1, 2025

Automatic Weather Station: An Overview of Its Functionality and Applications

March 14, 2025