Mitt Romney: Environmentalists' Next Great Ally?

>

Utah Senator Orrin Hatch has decided 42 years are enough. After orchestrating the reduction of two national monuments and a sweeping tax overhaul, Hatch announced Tuesday he would retire at the end of his term, in early 2019. There was speculation that Hatch would run again—President Donald Trump asked him to do so—but the influential senator reportedly followed the advice of his family (and 78 percent of Utah voters) and chose retirement.

Political analysts in Utah and Washington, D.C., believe Hatch’s seat will be filled by Mitt Romney, the former Massachusetts governor and 2012 GOP presidential candidate. Romney is incredibly popular in Utah: He earned nearly 73 percent of the vote there when he ran for president. And while Romney hasn’t made an official announcement, it seems a near certainty that he will throw in for senator. (Moments after Hatch said he’d resign, Romney changed his Twitter location to Utah.)

Unlike Hatch, Romney has not been chummy with Trump, who is deeply unpopular in Utah. There is wide speculation that Romney might even become a defiant force against the president. In a searing speech during the 2016 election, Romney called Trump “a phony, a fraud.” There’s good reason to believe, however, that this defiance won’t translate to the environment.

True, as governor of Massachusetts, Romney championed pollution control, fuel efficiency, and phasing out greenhouse gases. But that changed drastically when he became a presidential candidate. This is why, when thinking of his environmental record, it helps to look at two Romneys.

Not even a month into his governorship, Romney squared off with coal plant workers who said he was threatening their livelihoods. It was February 2003, and Romney had just denied a coal plant’s request to extend a deadline to clean up its emissions. Picketers were concerned about their jobs, but Romney had a more visceral worry. “I will not create jobs or hold jobs that kill people,” he said. “And that plant, that plant kills people.”

A Republican championing a coal cleanup is pretty much unthinkable today—all of Massachusetts’ coal-fired plants were shuttered by summer 2017—but Romney was progressive on many fronts during his governorship. He created a holistic office that oversaw transportation, housing, energy, and environmental policy and appointed a longtime environmental lawyer, Doug Foy, to run it. Also in 2004, Romney released the Massachusetts Climate Protection Plan, which promoted hybrid cars to lower emissions to 1990 levels.

“This plan is going to reduce pollution. It’s going to cut energy demand. It’s also going to nurture job growth and boost our economy, because reducing greenhouse gases has multiple benefits,” he said at the time.

Most striking was Romney’s involvement in a regional cap-and-trade plan. Working with other states in the Northeast, Massachusetts officials spent two years formulating the plan, only to have Romney back out in the final stages. “Industry opposed it,” the New York Times wrote in 2012, “and some former Romney policy advisers say his political team feared that it would doom his chances for the presidency.”

As Governor Romney became candidate Romney, his transformation intensified.

Romney’s no vote on the cap-and-trade plan was indeed a talking point during his presidential campaign. “I do not believe in a cap-and-trade program,” he told a Pennsylvania audience during the primary. “By the way, they don’t call it ‘America warming,’ they call it ‘global warming,’ so the idea of America spending massive amounts, trillions of dollars to somehow stop global warming is not a great idea.”

To differentiate himself from President Barack Obama, Romney abandoned many of his previously held positions on the environment. After championing fuel efficiency in Massachusetts, he called Obama’s fuel-efficiency standards overbearing. He promised to end renewable-energy subsidies if elected president, even though he allocated $24 million to similar projects as governor. The onetime castigator of coal was suddenly in favor of the sector, arguing that Obama’s regulations “would prevent another coal plant from ever being built.”

Romney’s campaign rhetoric was consistent with current GOP talking points. He said more federal land should be opened up to drilling and states should handle the regulations. He felt the EPA shouldn’t police carbon dioxide emissions and thought drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was a good idea. His campaign energy plan proposed opening up more offshore areas to drilling, finishing construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, and reducing overall regulations on extraction industries. “Energy independence” was the new buzzword. There wasn’t much talk anymore of air quality.

Romney’s environmental dance seems to correlate with the changing ideology of his constituents. In Massachusetts, he was governor of a liberal state, which dragged his politics to the left. Come 2012, the Tea Party movement was in full swing, and national politics on both sides had galvanized toward extremes. So Romney followed.

If he wins in Utah, Romney would be a senator in one of the country’s most conservative states. So while his recent behavior suggests he might break from the mainstream GOP’s fealty to Trump, breaking away from conservative environmental policies seems much less likely.

You May Also Like

Sprunki: A Comprehensive Exploration of Its Origins and Impact

March 19, 2025

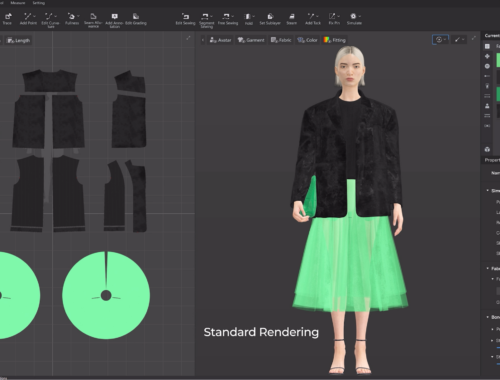

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025