Leadership, what leadership?

Leadership, what leadership?

Conventional wisdom offers no guide to the EU’s current leadership problems.

Who leads the European Union? In Paris, Berlin and London, the established answer is that the EU is led by some configuration of the three largest member states: Germany, France and the United Kingdom. The view in other national capitals is different. Some countries charitably attach importance to the president of the European Council (Herman Van Rompuy) and the president of the European Commission (José Manuel Barroso). Some still believe that the member state that for six months holds the presidency of the Council of Ministers is leading the EU.

A case could perhaps be made for each of these answers, by a class of political science students in need of intellectual exercise. But if the question is re-phrased slightly, to make it more specific in time – who is leading the European Union this week? – then Europe’s problems are thrown into sharper focus.

At the beginning of this week, Europe was trying to assess the damage of a G20 summit that seemed to promise more instability rather than less. The eurozone’s sovereign-debt crisis was taking another turn for the worse, with jittery bond markets betting on an Irish default.

It was a moment of some importance to the EU. But looking around the national capitals of the EU at that moment, it was hard to see where intelligent leadership might come from.

To start with the most histrionic: Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s president, was reshuffling his team of government ministers in a desperate attempt to restore his political fortunes. Yet so great is Sarkozy’s own unpopularity that he was constrained about what changes he could make. He might have wanted to sack François Fillon, the prime minister, but could not do so. A potential rival for the presidency, Jean-Louis Borloo, left the government.

Meanwhile Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, was at a party congress of her Christian Democrats (CDU), trying to resolve rivalries and calm discontent. A year ago, it seemed that by escaping the grand coalition and striking a deal with the liberals, Merkel was about to embark on a different style of government. The changes are not as great as we had been led to expect. At times the difficulties in the CDU’s coalition with the Free Democrats seem remarkably similar to differences in the CDU’s previous coalition with the Social Democrats.

Click Here: Putters

David Cameron, the British prime minister, seems to have a bit more room for manoeuvre politically. His coalition creaks at times – notably over housing benefits and student fees – but it is holding together. On the other hand, the economy is in dire shape and his government is driving through drastic cuts to the public sector. Even if Cameron did have greater freedom to show leadership in Europe than either Sarkozy or Merkel, he shows little inclination to use it. His Eurosceptic instincts are still sharp and the UK was in its customary role this week – blocking a deal on the EU budget.

Further down the EU’s hierarchy, Italy’s government is dissolving slowly. Four ministers resigned this week. Votes of confidence are scheduled in both the senate and the lower house of parliament. The chief preoccupation seems to be whether a national budget can be agreed before the votes of confidence. Silvio Berlusconi is well nigh irrelevant to the EU.

Spain’s government is on both its heels and its uppers, if that is physically possible. José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero’s unpopular government is on the defensive politically. The economy is in a dreadful state and the public finances are teetering on the edge of the eurozone’s debt crisis, threatened by that all-consuming ‘contagion’.

So you would have to turn to Poland to find a government whose leadership is secure politically and economically.

Note, en passant, that the Netherlands has a minority government and Belgium has a caretaker government – both of them founding members of the EU that have contributed much to its development.

In theory, this need not affect the EU adversely. The decisions taken by the member states in the Council of Ministers are not taken by a weighting of the governments’ standings in opinion polls. It is possible to look back and find moments in the EU’s history where a group of weak national governments took significant – and lasting – decisions.

But, in practice, there has to be a detrimental effect: at the EU’s core, there is a desperate lack of confidence. National leaders who are struggling to lead their own countries are barely in great shape to lead the EU. Yes, there will be moments when they get their acts together – usually when a crisis occurs and their senior advisers insist that they turn their attention to some pressing international matter. But there will not be continuity. There will not be a strategy put together by a political leadership that wants to maximise the EU’s chances.

And even relatively low-key, humdrum EU business will be affected. National governments that do not command the support of their own voters will be circumspect about signing up to EU legislation. They struggle to deliver their domestic constituencies to the EU cause.

The Lisbon treaty was supposed to have resolved that hoary old question of Henry Kissinger’s – when I want to phone the EU, whom do I call? When Van Rompuy and Barroso meet Barack Obama at the EU-US summit on Saturday, they will be giving a predictable answer (call me! call me!). But the truth is that he could call any of them: it won’t make much difference.

You May Also Like

シャーシ設計の最適化手法とその応用

March 20, 2025

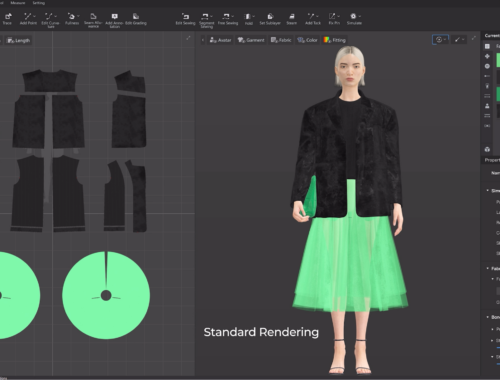

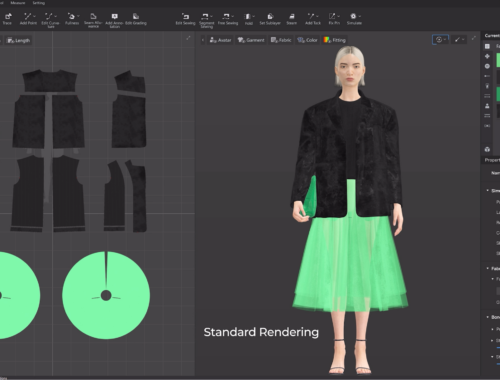

The Future of Fashion: How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing the Industry

February 28, 2025