Lawsuit Challenges Trump's Potomac Closures

>

Twenty-five miles northwest of the White House is a two-mile length of the Potomac River where the water relaxes before it crosses an earthen dam near the Seneca Break rapids. It’s the perfect spot for kids at a nearby summer camp to put in their canoes. It’s also a favorite training area for the U.S. Whitewater Team. Snowy egrets and blue herons land in the calm pool, and for locals it’s easy to paddle out and feel a world away from the D.C. chaos. Or at least it was.

Across the river is the Trump National Golf Club in Loudoun County, Virginia, one of the courses where the president has spent nearly a quarter of all his days in office playing golf. In the name of keeping the commander-in-chief safe, last year the U.S. Coast Guard began closing off this section of the Potomac any time Trump felt like hitting a round. Since then, kids on the water, even a group of kayaking wounded veterans, have been chased down by patrol boats and told to leave.

The closure is open-ended, with almost no forewarning. It was also done without letting the public know, which, according to a lawsuit filed last Thursday by the legal watchdog group Democracy Forward, is illegal.

“Last year it was just awful, and it was happening day after day,” says Barbara Brown, head of the Canoe Cruisers Association, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

Brown has been paddling the Potomac since the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration. She’s lived around D.C. most her life, so she’s used to the security convoys that come with living near the nation’s capital. But in all that time she says the river has never been closed like this. Just two weeks ago, for instance, she says a group of kayakers were practicing whitewater safety tests when a Coast Guard boat rushed near. The dedicated phone number her association calls to check on closures had said nothing about a presidential visit, but the officials onboard the boat demanded they leave—immediately. With the water level nine feet up, they were in a dangerous spot to portage. They argued for a bit, Brown says, and “eventually, the patrol boats let everyone go into a nearby canal”—technically in the no-go area, but a safer spot to disembark.

In the past, an area could be shut down for presidential security temporarily, but usually only for a short visit, and the closure was published on the Federal Register. The Trump administration seemed to stick to those guideline for the Potomac until June 2017, when for some reason it quietly decided on a bank-to-bank closure. To do that legally the Coast Guard needed to announce the change and open the decision to public comment, according to Charisma Troiano, a spokeswoman for Democracy Forward. Beyond inconvenience, Troiano says Democracy Forward is worried that, left unchallenged, this kind of broad, quiet decision to close a public space could become more common. “We’ve seen many instances,” Troiano says, “where this administration is rolling back rules or creating new rules without going through the proper process.”

The Trump administration has generally tended toward shortening public comment periods, or completely ignoring them. But in this case, public comments were only opened after the decision to close the river had been made. And when comments were allowed, more than 600 people wrote in, almost all in opposition.

“While government officials need to be protected, completely closing the river is overkill,” wrote one commenter. “Canoes, kayaks, and SUPs are not likely to be used as attack platforms.”

“America, land of the free?” wrote another. “Doesn't sound like it with attempts to take away freedoms to paddle.”

Part of the irony here is that Trump, before he was elected, unwittingly helped create this security concern. Trump bought the 800-acre club in 2009 (where membership fees range between $10,000 and $300,000) and quickly chopped down 465 trees to open views of the river. “You couldn’t see anything,” Trump complained at the time. Of course, now that the river is visible from the golf course, so is the commander-in-chief on the green. Still, kayakers argue it seems unlikely that an assassin would pick the Potomac to make an attempt on Trump’s life. And last year the head of the Coast Guard seemed to agree. Talking with members of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Former Coast Guard Admiral Paul F. Zukunft said he’d heard complaints about the bank-to-bank closure on the Potomac and wanted to work out a better situation. “We listened,” he said, “and we’re making that accommodation.”

But—perhaps especially in D.C.—talk is cheap, and nothing has been put in writing. So until that happens, any locals hoping to escape D.C. for a bit of relaxation on the Potomac must hope that the president isn’t doing the same across the river.

You May Also Like

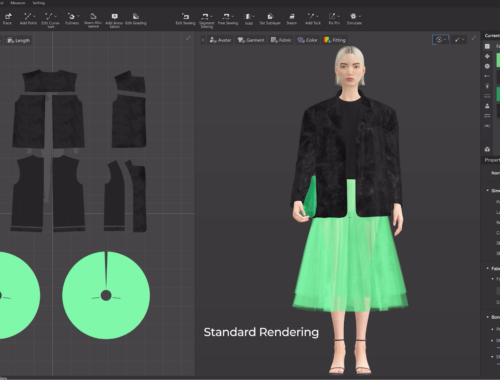

AI in Fashion: Revolutionizing Design, Sustainability, and Shopping Experiences

February 28, 2025

DO YOU KNOW HOW TO EXTEND THE LIFESPAN OF YOUR LASER CUTTING MACHINE?

November 22, 2024