In Search of the Vanished Destination

The Bering Sea is one of the deadliest places on the planet. But for the fishermen who harvest crab there every winter, their work had steadily been getting safer—they hadn’t lost a boat in a decade. That all changed on February 11, 2017, when the 110-foot Destination disappeared off the coast of Alaska with its six-man crew.

It was close to midnight on February 9, 2017, when the Destination left its Alaskan harbor for the last time. The lights of Unalaska, the regional fishing hub, slowly faded into blackness as the vessel made its way out into the Bering Sea and cut a path north toward the Pribilof Islands, a tiny archipelago in middle of the vast emptiness between Alaska and Russia. The crew planned to drop off extra bait on Saint Paul, the northern island, before heading out to the crab grounds.

It was a trip everyone aboard had made dozens of times. The Destination’s captain, Jeff Hathaway, had been a crab fisherman for 40 years and probably spent as much time in the area between Unalaska and the Pribilofs as his own backyard. He usually drove most of the way, with the other five crew members taking shifts on wheel watch at night.

The wind was starting to pick up from the northeast as a cold front pushed down from the Arctic. Saint Paul sits 275 miles northwest of Unalaska—a day’s trip for a boat traveling at a steady clip. As the Destination headed that way, it was riding in the trough, broadside to the wind and waves, taking all the spray and weather on its starboard side. That, along with a full load of crab pots on its back deck, would have exaggerated the boat’s side-to-side roll. By the time dawn broke, the Destination’s course had taken it almost 100 miles from land. It was cold enough that nearby boats reported accumulating a thick layer of ice from freezing spray.

“F/V Destination, Do You Copy?”

Listen to Outside’s podcast about the Destination.

Listen now

At 1:30 p.m. on February 10, the vessel’s automated tracking system showed the Destination turning to the northeast, pointing its bow into the waves, and slowing down. Jogging, as it’s called, is a way to make a boat more stable. It’s common when the crew is out on deck or when there’s a problem, like loose chains on the pot stack. In winter, crabbers will sometimes jog as the crew breaks ice off the boat to keep it from getting top-heavy. But clearing any significant quantity of ice takes hours, and the Destination was back on its way in just 20 minutes.

The vessel kept a steady course until 10:10 p.m., when it slowed down and jogged for a second time. For 30 minutes, the Destination faced into the wind at a slow crawl until, as before, it continued on its way toward the islands. It was strange for the boat to jog twice in such quick succession, but if something was wrong, the crew didn’t radio anyone about it.

Around 5 a.m. on February 11, the vessel reached the southern tip of Saint George Island, the southernmost of the Pribilofs. It would have been impossible to see the island in the dark, but the wind and seas would have calmed in its lee. In rough weather, boats often shelter behind the island, but the Destination didn’t stop. An hour later, it was back in the open ocean, maintaining its northwesterly course toward the processing plant on Saint Paul. The boat was on track to arrive around 8 a.m.

The Destination had just barely cleared the island when it slowed down and turned to the northeast, once again jogging into the waves. For two minutes, the vessel continued traveling in a straight line at three knots. Then, at 6:12, the bow abruptly swung hard to starboard, pointing the boat almost due east. Even though it was moving slowly by then, the sudden change in direction would likely have caused it to pitch to one side. That jolt would have been the first sign for most of the crew that something was seriously wrong—at that hour, almost everyone would still be sleeping below deck.

For the next two minutes, the Destination continued to spin, tracing a 270-degree arc, until the bow was facing due west—out toward the empty sea.

If anyone was in the wheelhouse at that moment, it would have been abundantly clear that disaster was imminent. Boats aren’t meant to spin like that. But there was no mayday.

Then, at 6:14 a.m., the Destination’s tracking system stopped transmitting.

The Bering Sea has a well-deserved reputation as a dangerous place. One author called it “where the sea breaks its back”—a nod to the massive storms that regularly churn across the region, bringing hurricane-force winds and multistory waves. It’s also the most productive fishing grounds in the United States, with boats hauling in more than $1 billion worth of seafood every year. The most famous of those harvests is crab, which has been dramatized in the reality television series Deadliest Catch.

In the 1990s, Bering Sea crab fishing lived up to that name. Fishermen raced each other in cocaine-fueled competitive derbies, staying awake for days on end and loading as many pots and as much crab as possible onto their boats. The results were catastrophic. During the decade, 12 boats sank and 73 crab fishermen died. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an agency not known for exaggeration, called the fatality rate “astronomical.” Even so, young men arrived in droves for fishing jobs, inspired by the extraordinary high pay—one could make $100,000 in a season. The Bering Sea was the the last outpost of the Wild West. Unalaska, which had been a small, mostly Native fishing village with a few hundred permanent residents, became a boomtown. There were almost nightly brawls at the Elbow Room, a bar that Playboy once ranked as the second most dangerous in America.

Then, in 2005, the same year Deadliest Catch started airing, everything changed. Fisheries managers started divvying up the catch, and each boat was given a share of the crab harvest—a quota—which it could fish at its leisure. That, combined with new safety regulations, transformed the industry. The derbies that inspired the show ended. Between 2006 and 2016, not one boat sank and just a single crab fisherman died on the job.

So when the Destination went missing, it didn’t take long for the news to spread across the fishing fleet. The reaction was almost unanimous disbelief. Hathaway and his crew were veterans of the Bering Sea. Many of them had been at it for decades. Then there were the circumstances of the boat’s disappearance—in unremarkable weather, close to land, and with no mayday. It didn’t make sense. “If I could line up the fleet of 70 boats, that boat, with that guy running it—it would be pretty high on my list of boats that wouldn’t have a problem,” says Mike Mathisen, captain of the F/V Karin Lynn, another Bering Sea crabber.

Less than an hour after the Destination stopped transmitting, Coast Guard rescue aircraft were preparing to launch for the vessel’s last known location. But the vast distances of the Bering Sea meant that it would be hours before they arrived.

Exactly one week before the Destination disappeared, the boat pulled into its home port of Sand Point, Alaska, after 27 days fishing for cod. It was rare for the Destination to visit town during the season, but the six-man crew was exhausted and it was Super Bowl weekend. They’d have four days on land before setting off again for the upcoming snow crab harvest.

The Destination tied up to the dock at the east wall of the harbor. At 110 feet long, the blue-and-white vessel dwarfed most of its neighbors. In earlier decades, Sand Point—a town of 1,000 that feels considerably smaller, with few paved roads, one restaurant (Chinese), and no stoplights—had been home to a fleet of large Bering Sea fishing vessels. But industry consolidation sent most of them 3,000 miles south to Seattle. It was a point of pride for the local community that the Destination still called Sand Point home, and everyone knew the crew, even though most of the six lived elsewhere in Alaska or in the lower 48.

Thirty-six-year-old deckhand Darrik Seibold, who’d spent about seven seasons on the Destination, was the closest to a full-time resident. A former high school football player nicknamed Superman because he was, in the words of a friend, “one strong son of a gun,” Seibold moved to Sand Point in 2009. He’d struck up a relationship with a local woman, Amber Karlsen (nee Gundersen), and in 2014, they had a son, Eli. Seibold had been a nomad for most of his life, often picking up and leaving with little more than his sketchbooks and journals, but Eli grounded him. The relationship with Karlsen had recently hit a rocky patch, according to his family and friends, but Seibold still spent most of his time in Sand Point with Eli. He liked to take his son four-wheeling in the tundra near town and hiking on the island’s big, sandy volcanic beaches. There wouldn’t be time for those things on this quick stopover, though: There was lots of work to be done on the boat.

The first order of business was to rerig the Destination’s 200 pots—seven-by-seven-foot rectangular cages of steel and webbing—for crab season. The crew worked on the dock, looking out over the brown rolling hills and white-sand beaches of Unga Island, part of the Shumagin archipelago, at the far eastern end of the Aleutian Island chain. During winter, it’s common for the wind to whip through the passage between the islands at almost hurricane force, but it had been a relatively mild year, and the weather stayed calm as the crew worked its way through the stack of pots. Since 2005, most boats had cut down on the number of pots they carried, to save weight, but Hathaway liked his 200-pot configuration. It had been his go-to for years.

Seibold worked a little more slowly than usual—he had tweaked his hip the previous month, the latest of a long string of fishing injuries. Just after Eli was born, Seibold caught his hand between a dock piling and the steel hull of a small boat, crushing his thumb and index finger. It took surgery and metal pins to fix it, but he was back fishing as soon as he could make a fist.

As a kid, Seibold had bounced back and forth between his mother’s home in southeast Alaska and his father’s home in Washington. In Alaska, he spent time on his grandfather’s charter boat, catching halibut and salmon. After high school, he tried various jobs but eventually fell into fishing full-time—the camaraderie and athleticism were like the football teams he had played on. It was also good money: When the fishing was going well, Seibold could make $30,000 in a few weeks. He hoped to make at least that during the upcoming crab season. Even so, Seibold had started talking about leaving the industry.

“He would go to the Bering Sea and be gone three months at a time,” Karlsen says. “It was too long for him when Eli was growing up. Eli was his life.”

Seibold wanted to find a job that would allow him to come home to his son at night—maybe carpentry or construction. He was going to start looking as soon as the season ended.

Fully loaded, the Destination left port on the morning of February 8, then headed west down the Aleutian chain toward Unalaska. The weather had stayed relatively nice, and the boat chugged along at eight knots.

In Unalaska, the crew needed to pick up more bait—the squid, cod, and herring fishermen use to attract crab. The Destination’s bait freezer was already full, but word was that the fishing had been slow out on the grounds and boats were burning through their reserves. The Destination’s owner, a fisherman turned entrepreneur named David Wilson, told the crew to stock up before heading out. Stopping in Unalaska would add a day to the trip and extra weight to the already heavy boat, but without bait, there would be no crab.

Before arriving in port, Hathaway called the Coast Guard. Since 1999, crabbers have been required to give the agency 24 hours notice before leaving for the fishing grounds. The rule is supposed to give the Coast Guard a chance to inspect crabbers for overloading before they leave port, but the inspections aren’t mandatory. The Coast Guard petty officer who answered the phone offered to send someone over, but Hathaway declined. He told them he’d been through an inspection before the crab season in October, although the Coast Guard has no record of that.

As the Destination switched docks in the Unalaska harbor, it passed the F/V April Lane’, headed the other way. The five-high stack of crab pots on the Destination’s back deck made Rick Fehst, captain of the April Lane’, do a double take. “They are not leaving [Unalaska] with that stack on,” he thought. Fehst had seen the weather forecast, which called for heavy freezing spray with temperatures dipping into the teens. Bad weather is a fact of life in the Bering Sea, but the spray poses particular challenges for crab boats carrying pots. The pot stack provides a large surface area for the water to turn to ice; enough accumulation can make a boat top-heavy and prone to roll over.

Fehst called his crew up to the wheelhouse for a teaching moment as the Destination passed. If he were running that boat, Fehst explained, he would ditch the top layer or two of pots. Better yet, he told his crew, he would stay in port until it warmed up. One of Fehst’s crew members shot a video of the Destination on his phone. Then everyone went back to work. Fehst didn’t hail the Destination on the radio or reach out to the Coast Guard. “It’s not my business to call a captain out,” he said. “It’s not our culture to do something like that. We all just figure if you’ve gone to the wheelhouse, you know what you’re doing [and] you’re going to make the right choices.”

He didn’t know Hathaway well, but he knew that he was an experienced mariner. Hathaway started fishing in the Bering Sea in the 1970s, after dropping out of high school, and had been captain of the Destination since 1993. Within the fleet, he was known as a perfectionist for his color-coordinated buoys and perfectly aligned crab pots. Aboard the Destination, Hathaway had a reputation for his quirks, including his habit of wearing pajamas while on the boat—usually plaid, but sometimes a pair featuring the blue and red fish of Dr. Seuss fame.

Hathaway was well aware of how dangerous the Bering Sea could be; he had almost lost his wife, Sue, to it. The couple met on a fishing boat in 1979, when she was a cook and he was an engineer. They married in 1984. The year before, Sue was aboard the 98-foot Arctic Dreamer as it headed into port, fully loaded with crab, when a wave hit the vessel and it capsized. The six crew members barely had time to put on their survival suits and issue a mayday before the boat sank, leaving the fishermen swimming for their life raft. Sue went back to Alaska for one more season before giving up on fishing for good. She and Hathaway lived in Port Orchard, Washington, where they raised their daughter, Hannah Cassara.

Hathaway kept fishing, taking over as captain of the Destination in 1993. As Cassara grew up, she wrote letters and postcards to her dad during his three- and four-month absences. During his infrequent visits to port, Hathaway would call home on scratchy connections and tell Cassara how peaceful it was to throw off the lines and head out to sea. In recent years, since the advent of satellite phones, he made a point to call home every night. There were times over the years when Hathaway tried to quit fishing and find work closer to his home in Washington. But none of those efforts—including a failed oyster business, ostrich farming, and a gig patching asphalt—ever stuck. “His passion was definitely fishing,” Cassara says. “It was what he knew best.”

From Unalaska, Hathaway called Wilson, the Destination’s owner, to let him know they would be leaving for Saint Paul that night. During the call, Hathaway mentioned that the stuffing box—the watertight seal around the propeller shaft—was leaking, but that they had tightened down the bolts and it seemed like the problem was fixed. Leaky valves and clogged filters are common problems for any commercial fishing vessel, but the Destination had also been plagued by some bigger mechanical issues in recent years. Infrequently but unpredictably, the rudder would stick hard to one side, causing the boat to suddenly veer in one direction until the engine could be restarted. It was enough of a concern that Wilson had the whole steering system flushed when the Destination was in Seattle for repairs in 2016. They needed to make a small repair to the exhaust system, and then they would be on their way.

With the boat tied up at the dock, Hathaway went to pick up spare parts for the exhaust system. While he was gone, Seibold’s brother, Dylan Hatfield, stopped by. Eight years Seibold’s junior, Hatfield was also a crab fisherman and had worked on the Destination until 2014. The two were recognizably related but had radically different personalities: Seibold was reserved, while Hatfield was a self-described social butterfly. He bounced around the boat, chatting with his former crewmates. The atmosphere was normal, Hatfield said later. The men were “laughing and telling stories and having a good time.”

The group included Larry O’Grady; at 55, he was the most senior deckhand. He’d been fishing almost as long as Hathaway and liked to regale the crew with stories about the glory days. The boat’s engineer, Charles “Glenn” Jones, 46, was another veteran, having fished on and off for decades. He was recently married and had three little kids. The other deckhands were Ray Vincler, a 32-year-old local raised in the tiny village of Akutan, just one island over from Unalaska, and Kai Hamik—the youngest, at 29—a square-jawed former college baseball player from Arizona.

In contrast to the high-drama interpersonal clashes often portrayed on Deadliest Catch, the Destination’s crew mostly got along. They liked to play pranks on one another and kept up a running joke about O’Grady allegedly perming his hair. In one spoof video captioned “NOT DEADLIEST CATCH,” Hamik spliced together footage of the crew pulling pots with video of Jones showing off his dance moves on deck. The crew respected Hathaway. “Jeff was dad,” Hatfield said. “That was what we called him on the boat.”

During Hatfield’s tenure, Hathaway would sometimes gather the crew in the galley to show old videotapes from boats he’d worked on in the 1970s. He would point at the video periodically and say, “That guy’s dead, that guy’s dead, that guy’s dead.” At the time, it seemed to Hatfield that knowing fishermen who had died was a rite of passage.

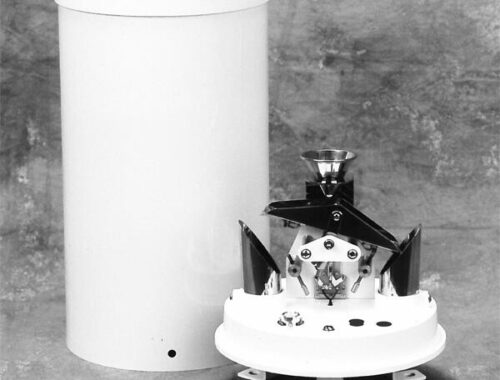

Bill Prout was in the wheelhouse of his crab boat, the F/V Silver Spray, getting ready to leave Saint Paul harbor, when he heard the Coast Guard’s first callout for the Destination over the radio. It was around 6:30 a.m. on February 11, and the broadcast noted that the Destination’s emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) had been activated near Saint George.

At first, Prout didn’t think much of it. He had been in the wheelhouse and hadn’t heard a distress call from the vessel. Also, he knew the Destination by reputation, and it wasn’t the kind of boat likely to have problems. EPIRBs are designed to activate on contact with the water, communicating to the Coast Guard that a vessel is in trouble even when a boat is out of radio range. In practice, however, EPIRBs are often set off by far less dramatic circumstances—someone chipping ice off the boat or hitting the wrong button. Prout figured the Destination’s crew had knocked the EPIRB accidentally. He didn’t change course. The Silver Spray was 23 miles from the Destination—at least two hours away.

It wasn’t until 6:54 a.m. that the Coast Guard called Prout directly to ask if he could hail the Destination.

“Destination, Destination, Destination, this is Silver Spray, receive us on Channel 16.” There was no answer. Prout tried again and again. After the third time, he started worry. He plotted a new course toward the Destination.

Along the way, he turned the Silver Spray’s floodlights on and off, hoping to see the flash of a strobe or the shadow of a hull. But other than the reflection of his own lights in the water, everything was dark. Prout arrived at the Destination’s last known position around 9:15 a.m., three hours after the EPIRB alert.

When dawn finally came, the first thing Prout spotted was a pair of buoys. Then he smelled the diesel and spotted the fuel slick. “That’s when we really started looking for a life raft,” he said. The Destination, he knew, was gone.

More than four hours had passed since the initial distress signal. In 32-degree water, someone wearing street clothes can’t survive longer than a few minutes. Even in a fully sealed immersion suit, which boats are required to carry, most estimates of survival time are between four and six hours.

Soon, the Coast Guard aircraft arrived. The helicopter was carrying not only a rescue team, but also a cameraman from Deadliest Catch. He filmed as the helicopter crew directed Prout to the still-transmitting EPIRB. It floated alone on the surface of the water.

Hannah Cassara had just come in from feeding the horses at her Washington home when her mother called. It was 8:30 a.m., and this was already Sue Hathaway’s second call of the morning. Cassara’s heart sank at the ring. Her uncle was in the hospital with complications from surgery, and the earlier phone call had been to let Cassara know he was in critical condition. For her mom to call back so soon, Cassara knew the news must be bad. “I thought my uncle had died,” she said.

When she picked up, Cassara heard Sue crying on the other end of the line.

“Hannah, they found the EPIRB on the boat,” Sue said.

For a moment, she couldn’t process what her mother was saying. Hathaway had missed his usual evening call the night before, and Cassara had been hoping to hear from him in the morning so they could talk about her uncle. It had never even occurred to her to worry about her dad.

“He must be in a life raft,” Cassara thought. “They do their drills. They know the safety stuff. The safety stuff is so important to Dad.”

Panicked, she and her husband packed up their car to head 100 miles north to her parents’ house. As they drove, Cassara kept expecting the Coast Guard to call and tell her they had found the life raft. She was waiting to hear her dad’s voice coming over the line from far away, just as it always had.

It wasn’t until several hours later that Hatfield, Seibold’s brother, heard the news. His morning flight out of Unalaska had been canceled, and he was back on his boat, taking a nap, with his phone off. Hatfield woke up to his captain knocking on the door. Rubbing away the fog of sleep, Hatfield asked him what was happening, and his captain broke the news that the Destination’s EPIRB had gone off.

“I knew right then they were gone,” Hatfield told me.

The question that remained: Why had the boat sunk? There was no obvious explanation for its sudden and fatal disappearance.

The Coast Guard searched the area of the Destination’s last transmission for days, hoping for a miracle, or at least a body. When the Silver Spray retrieved the EPIRB, the crew found that it had been taped to a coil of rope, a highly unusual setup for an emergency beacon. “Someone rigged it!” a crew member shouted as they hauled the EPIRB aboard. But after searching more than 6,000 square miles, the Coast Guard failed to locate a life raft or anyone in a survival suit. “It’s a different type of grieving,” Hatfield told me last fall. “There’s no closure, no body, no grave. They’re just gone, dust in the wind.”

Understanding why the boat had sunk would take longer. In April, the Coast Guard discreetly coordinated a search for the wreck using sonar but didn’t find anything in the vicinity of the Destination’s last transmission. On a second attempt in July, with an expanded search area, they finally located the boat. The Destination was resting on its port side in 250 feet of water, more than two miles from where it last transmitted. Grainy sonar images, taken from the surface, showed the boat was upright and intact, although it appeared to be missing the back half of its pot stack.

The Coast Guard sent an underwater vehicle to take photos of the wreck, but the current was too strong and kept pushing it off course. One of the only clear images it managed to capture was of a small section of the stern of the vessel. Beaming through the murky waters were big, white letters: DES.

In August, the Coast Guard convened a marine board of investigation to determine what happened, in hopes of preventing similar accidents. Investigators called on 44 people to testify over ten days.

There’s a recurring theme in most disasters, especially those at sea: It’s never a single thing that dooms a vessel. Rather, a series of small decisions and circumstances together add up to a catastrophe. Those factors often start piling up long before the actual accident.

A few serious issues came to light during the testimony. First, there were the 200 crab pots that the crew loaded in Sand Point. According to the Destination’s stability book—a manual for how to properly load a vessel—200 pots was well within its operating limits. But the manual hadn’t been updated since 1993. The naval architect who wrote it estimated each pot’s weight at 700 pounds. That may have been accurate at the time, but it wasn’t in 2017. When the Coast Guard pulled up one of the pots from the wreck site, they found it weighed closer to 850 pounds. With the extra weight of the pots, plus the additional bait, the Destination was already tens of thousands of pounds heavier than accounted for in its stability book—and that didn’t include the weight of ice accumulation from the freezing spray.

When a boat has too much weight up high, it starts to lose stability. When that happens, the boat’s roll becomes more pronounced and the steering can become sluggish. The less stable the boat, the less it takes to knock it over—a big wave, a sharp turn, a sudden change in speed. Former crew members testified that it was unusual for the boat to have jogged twice on its way to the islands. If the Destination was already having problems, icing would have exacerbated those issues.

Finally, the Destination’s life raft was stored behind the wheelhouse in a cradle with an automatic release. Like the EPIRB, the life raft should have automatically deployed on contact with the water, but rescuers never found it. Did it deploy and sink? Or did it never deploy at all?

The Coast Guard is expected to release the findings of its investigation sometime this year; that may provide some more definitive answers. But there are still likely to be outstanding questions—like why there was no mayday.

The day of Seibold’s memorial in Sand Point was cold and rainy, but dozens of people came out anyway. It was April 16, Seibold’s birthday—he would have been turning 37. Instead, the community gathered on the beach to bid him farewell. Karlsen had built a small boat and attached a Superman cape to the mast. Eli added a basket of Easter eggs that he wanted to send to his father. He knew that his dad’s boat had sunk, but he hadn’t quite yet grasped what that meant and kept asking Karlsen to go find Seibold.

As Karlsen stood on the beach, she thought about how Seibold must have felt once he realized he would never see Eli again. “He just wanted so bad to spend his life with Eli,” she said. “Eli was just his pride and joy.”

She thought about what she would tell her son about his dad, once he was old enough to understand, and wondered if Eli would someday want to follow in Seibold’s footsteps and go to sea. Karlsen knew that when it came down to it, she probably wouldn’t have much say in that decision. “When he gets older, [Eli is] going to want to know about all of this, and his dad,” she said. “He’ll make that decision himself.”

Hatfield, Seibold’s brother, spent the summer after the accident fishing salmon in the more protected waters of southeast Alaska. But when fall came and king crab season neared, Hatfield found himself staring down an empty suitcase as he tried to talk himself into going back to the Bering Sea. “I couldn’t even get myself to pack,” he said. He had been having nightmares for months about what might have happened in those last few minutes on the boat. He imagined how it must have felt as his brother was pulled down into the depths. Even so, Hatfield didn’t want the dreams to end.

“It’s kind of nice to see everyone’s face,” he explained.

The day he was supposed to leave for the crab season came and went, Hatfield’s suitcase still empty.

“My heart’s just not in it anymore,” he said.

Stephanie May Joyce produced the podcast “F/V Destination, Do You Copy?” for Outside. Mengxin Li is an illustrator based in New York.

You May Also Like

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025

Sprunki: A Comprehensive Exploration of Its Origins and Impact

March 19, 2025