In 'Eager,' Ben Goldfarb Champions the Beavers

>

If you care one whit about wildlife, you’ve probably seen the YouTube hagiography “How Wolves Change Rivers.” If you’re not among its 39 million viewers, here’s the gist: After the destruction of Yellowstone’s wolves, the story goes, unchecked herds of elk grazed the park’s streamside plants to nubbins. Denuded riverbanks slumped into their channels, leaving behind bare, incised, eroding waterways.

Wolf reintroduction in 1995 changed all that. Not only did Canis lupus thin the herds, wolves also frightened their prey away from narrow valleys, deathtraps whose tight confines made elk easy pickings—a dynamic dubbed “the ecology of fear.” Safe from hungry elk, riparian aspen and willow thrived. Wildlife from flycatchers to grizzly bears returned to shelter and feed; eroding streambanks stabilized; degraded creeks transformed into deep, meandering watercourses. Wolves had apparently catalyzed a trophic cascade, a process in which the influence of top predators—lions in Africa, dingoes in Australia, even sea stars in tide pools—ripples through foodwebs, changing, in some cases, the vegetation itself. “So the wolves, small in number, transform not just the ecosystem of the Yellowstone National Park…but also its physical geography,” enthused the video’s narrator.

“How Wolves Change Rivers” transfixed me when I first saw it. I wasn’t the only one: I’ve since heard the Yellowstone wolf tale repeated at conferences, seminars, and even on the lips of baristas in Scottish fishing villages. “This story—that wolves fixed a broken Yellowstone by killing and frightening elk—is one of ecology’s most famous,” wrote the biologist Arthur Middleton in the New York Times. And it’s a great story: imbued with hope, easily grasped, bespeaking the possibility that our gravest mistakes can be remedied through enlightened stewardship. We live in a world of wounds, quoth Aldo Leopold, but we can also play doctor.

There’s only small problem with the vaunted wolf narrative, Middleton added: “It’s not true.”

“Untrue” is, to my mind, too harsh. “Incomplete” might capture it better. Wolves have undoubtedly changed Yellowstone’s ecosystems, and in some river valleys they’ve done extraordinary good. But there are other valleys the canids haven’t managed to save, places that remain as degraded as they were on that January day, more than two decades ago, when reintroduction began. Yellowstone’s wolves are landscape benefactors, but perhaps not panaceas.

So what makes the salvational story incomplete? Well, for one thing, it elides the role of another species—an equally influential animal that, like the wolf, was for decades almost entirely absent from the park. Over 20 years after wolf reintroduction, most of Yellowstone’s streams are still missing their true architects.

More than a century ago, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem ranked among the finest capitals in all of Beaverland. Although trappers pillaged the region, Yellowstone’s beavers survived the fur trade unvanquished. In 1863, Walter DeLacy complained about the “numerous beaver dams” that frustrated his travels through the Madison drainage. The Earl of Dunraven, exploring the Upper Yellowstone River in 1874, remarked that “all the streams are full of beaver.”

There was a good reason why Yellowstone was so beaver-rich: The same otherworldly geysers and hot springs that entranced the park’s human visitors made it uniquely well suited to harboring aquatic mammals in winter. “These outlets, relatively clear of ice, afford unusual advantages for burrow habitations in their banks,” wrote superintendent Philetus Norris in 1881, “or for the construction, in their sloughs, of the…brush-and-turf houses of these animals.” Were it not for illegal trappers surreptitiously controlling their numbers, Norris speculated that beavers would overrun the park altogether. “Unmolested by man, who is ever their greatest enemy, the conditions here mentioned are so favorable to their safety that soon they would construct dams upon so many of the cold-water streams as literally to flood the narrow valleys, terraced slopes, and passes, and thus render the park uninhabitable for men as well as for many of the animals now within its confines.” In 1927, Milton Skinner, the park’s superintendent, estimated Yellowstone’s beaver population at 10,000, but added that the guess was likely “very conservative.”

Yet the park’s beaver boom was short-lived. By the time Robert Jonas, a graduate student at the University of Idaho, surveyed beavers in Yellowstone’s Northern Range the 1950s, he found little but ruins, like an archaeologist stumbling upon the overgrown rubble of an abandoned kingdom: empty lodges, derelict dams, chew scars darkened by the passage of years. “Of all the areas (previously) found to have significant beaver workings,” Jonas wrote, “none had any activity in 1953 nor was there any indication that beaver had inhabited those regions for several years.” Just three decades earlier Yellowstone had been Castor central. Now, despite all the protections afforded by a national park, it was a ghost town. What had gone wrong?

Beavers, Jonas realized, were collateral damage—the victims of backward wildlife management. In 1914, Congress had granted the Bureau of Biological Survey, an obscure agency tasked with controlling crop-eating birds and rodents, a sinister new remit: the destruction of wolves, coyotes, cougars, and other predators. Sheep and cattle were spreading across the West, and the government sought to purge the range of stock-menacing carnivores. Bureau agents bearing guns, poisons, and traps scuttled across the land under the orders of director Vernon Bailey, a man not known for mercy. “By watching near [wolf] dens in the early morning or at dusk before the young are taken out,” Bailey advised in one circular, “a good hunter is sometimes able to shoot one or both of the parents.”

Today national parks are strongholds for large carnivores. But when Bailey visited Yellowstone in 1915, he “found wolves common, feeding on young elk,” and urged the bureau to kill “without abatement until these pests are greatly reduced in numbers.” The new National Park Service became one of Bailey’s most enthusiastic clients. By 1926, the Park Service and the Bureau of Biological Survey had killed at least 122 Yellowstone wolves, 1,300 coyotes, and untold cougars. The campaign was largely motivated by the cynical politics of self-preservation. By eliminating predators, the Park Service hoped to reassure ranchers and Congress that future national parks wouldn’t threaten livestock. And without pesky wolves around, Yellowstone’s burgeoning elk, deer, and pronghorn herds would, in theory, spill out of the park, satisfying hunters. “To me a herd of antelope and deer is more valuable than a herd of coyotes,” superintendent Roger Toll opined in 1932.

Public pressure eventually ended the slaughter, but by then it was too late: The wolves were gone. Almost immediately, researchers realized how badly the policy had backfired. Exploding elk herds devoured vegetation as fast as it could grow, hastening soil erosion. “The range was in deplorable condition when we first saw it, and its deterioration has been progressing steadily since then,” a team of visiting scientists cautioned in 1934.

At first, the anti-predator campaign may have given beavers a boost. Wolves are inordinately fond of the delectable rodents: When scientists picked through summertime wolf scat in Alberta, they found nearly 60 percent of the samples contained traces of luckless beaver. In 1926, one researcher suggested that carnivore extermination had unleashed “what is probably an unnatural expansion of the beaver population.”

Soon after the final wolf fell, however, beavers found themselves squeezed out by other herbivores. Beavers in northern latitudes, recall, cache food in frozen ponds for the winter. According to ecologist Bruce Baker, the rodents are prudent about their stores, ignoring willow stems until the plants are large enough to furnish an adequate winter supply—around three years of growth. Beaver-chewed willows tend to coppice, growing back shoots after each cutting; beavers often harvest and rotate their coppices as diligently as any silviculturist. “There’s a rest period built into the system,” Baker told me.

Elk, by contrast, prefer aspen and willow at their youngest, greenest, and most tender. Nibbled incessantly by elk, willow can’t recover from browsing; eventually the plants die, depriving beavers of their winter larder. In his 1955 report, Bob Jonas didn’t pull punches: “The serious reduction of the favorable beaver habitat within the park boundaries can be attributed primarily to the overpopulation of elk.” Beaverland had ceded to Elktown.

In the mid-1980s, beavers finally found a champion. Dan Tyers, today a grizzly bear biologist for the U.S. Forest Service, grew up around Yellowstone, the son of a Park Service ranger. When, in 1978, Tyers landed a backcountry ranger gig in the breathtaking Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, the block of land just north of Yellowstone, he kept his eyes peeled for beavers. He saw ancient lodges and overgrown dams everywhere, but scant recent sign.

As Tyers ascended the Forest Service’s ranks, the shine wore off his ranger job. He grew disenchanted with the mundanity of checking permits and monitoring timber sales. He yearned to feel creative, to ask grand questions and seek meaningful answers. His supervisors were perplexed by his zeal, but they didn’t object when he proposed his big idea: reintroducing beavers into the Absaroka-Beartooth.

Tyers’s effort, which lasted from 1986 to 1999, remains one of the largest beaver relocations ever undertaken. The biologist live-trapped nuisance beavers on private property and transplanted them in public headwaters, even capturing the rodents on Ted Turner’s ranch after they lopped down the magnate’s shade trees. He moved the animals on horseback, in canvas-wrapped cages cooled by blocks of ice. Tyers turned his beavers loose in streams like Slough Creek and Buffalo Creek, waterways that flow south from the Absaroka-Beartooth into Yellowstone National Park, passing from Forest Service land to National Park Service jurisdiction as they go. Tyers knew there was a chance—indeed, a likelihood—that his beavers would follow the creeks into the park.

Sure enough, Tyers’ beavers soon trespassed. In 1996, Doug Smith, Yellowstone’s wolf biologist, surveyed its beaver colonies from the sky, his lanky frame folded up in the back of a circling Piper Super Cub. (Smith made sure to stop before hitting “observer fatigue”—a euphemism, he wrote, for “the puking point.”) During that first survey, Smith counted only 49 colonies in the entirety of Yellowstone. By 2007, however, the tally had nearly tripled, to 127 colonies. The spike, Smith noticed, was concentrated in the Northern Range, on many of the same streams where the Forest Service had released beavers. At last, Tyers figured, his wards had drifted downstream.

In the popular imagination, however, Tyers’ relocation tale lost out to a more compelling narrative: that, by allowing willows to regrow, wolves alone brought beavers back. Articles in National Geographic, the New York Times, and Orion Magazine attributed beaver recovery to wolf reintroduction, without once mentioning the relocation program that had quietly restocked the rodents just outside the park. Beavers became another link in the trophic cascade. This framing wasn’t inaccurate, per se, but it omitted Tyers’ meddling.

“The conversation made me think about spontaneous generation,” Tyers told me when I visited his Bozeman office, referring to the antiquarian theory that, say, maggots could simply arise, without progenitors, from rotting meat. “‘How did beaver get there? Well, they just appeared.’” He sat back in his rolling chair and shrugged. “Beavers started showing up in Yellowstone, and because of the park’s name recognition, it hit the news. Reasonably so—I’m not being critical. But all the while we’d been moving beavers into the backcountry and probably had 50 different active lodges and terraced dams that went on for a mile. Holy smokes, folks, if you just went a few miles north of the park and saw what beavers were doing there, you’d have a different view of the world.”

The media coverage glossed over another inconvenient truth: Despite the wolf reintroduction, and despite beavers’ incremental recovery, many Yellowstone valleys remained untransformed. Had Philetus Norris surveyed the Northern Range in 2006, he would have discovered that the soggy paradise he’d witnessed in the 1880s remained largely bone-dry and beaverless. The sad reality, some scientists suspected, was that a century of mismanagement had inflicted damage that neither wolves nor beavers could readily repair.

As long as beavers are back in Yellowstone, why does it matter whether wolves or relocations get credit for their return? Ask Dan Kotter, and he’ll tell you the reason is expectation management.

One June morning, Kotter, a PhD student at Colorado State University, drove me to Elk Creek, Exhibit A in the case for the limitations of the trophic cascade. In the 1920s, Elk Creek had been a beaver-built wonderland of open water, willow, and aspen; in the stream’s North Fork, one surveyor recorded 17 dams, including “a splendid new structure…more than 350 feet if measured along all the curves, and 5 feet high on the lower face.” But the concerted wolf-killing had allowed elk to feast here, outcompeting beavers for precious forage. Without plants and beaver dams to slow its flows, the creek eroded to bedrock, while its floodplain, now disconnected from the stream, devolved from productive wetland to fallow pasture. Millennia to create, mere decades to unravel.

Kotter and I scrambled through smooth brome and timothy into Elk Creek’s channel. A towering cutbank loomed eight feet above the ankle-deep flow, the eroded cross-section as black and rich as chocolate cake. Hardly a willow stem adorned the banks: The water table had plummeted so far, Kotter said, that roots couldn’t tap groundwater. “The only thing that could recreate this big wet valley would be beavers coming back,” Kotter explained. “But can beavers come back when there’s no food resource?” He shrugged. “I don’t think this site will restore itself in my lifetime.”

In other words: Wolves may well be boosting vegetation and stabilizing streams in many Northern Range valleys, yet some incised creeks have degraded too far to bounce back. Those doomed streams are locked today in the dreaded purgatory that Kotter calls the “alternate stable state.” Without tall willows to feed them, beavers can’t return; without beavers to irrigate them, willows can’t recover—a feedback loop of degradation. I’ve thought a lot about how to reconcile the competing Yellowstone stories, and here’s the best I can do: In many heavily grazed western landscapes, restoring beavers demands wolves. But some ecosystems are too damaged for even predators to salvage.

Nor are wolves the only way to alleviate the symptoms of elk overabundance. Four hundred miles southeast of Yellowstone, in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, a parallel ungulate explosion drove the park’s beavers nearly to extinction. By 1980, nary a beaver cavorted in Rocky Mountain’s Beaver Meadows. While Yellowstone tackled its elk glut with wolves, Rocky Mountain—which is practically next door to Denver—took a more cautious approach, encircling over 200 riparian acres with six-foot-tall fences and planting thousands of aspen and willow stems. Although the park’s elk population has descended to sustainable levels, beavers have recolonized only 10 percent of its suitable habitat, and landscape ecologist Hanem Abouelezz told me vegetation throughout much of Rocky Mountain still isn’t ready to support the rodents.

“If they just mow down all our plantings and den in the bank, that could really set us back,” she said. Park officials have discussed the possibility of installing artificial beaver dams to boost water tables and willow growth, but Abouelezz told me the idea was still embryonic. “We didn’t create this problem in ten years,” she said, “and we’re not going to fix it in ten years.”

Whether it’s appropriate to build artificial beaver dams in national parks is an ethical question as much as a scientific one. What do you value more: rapid recovery, or the relative naturalness of a hands-off approach? Without intervention, Yellowstone aficionados may have to wait a long time—centuries, perhaps—to glimpse the gloriously ponded Northern Range that scientists sloshed through in the 1920s. But maybe that’s okay. “Twenty years ago, Yellowstone was a dismal desert,” Bob Beschta, an Oregon State University hydrologist who’s among the leading proponents of the trophic cascade theory, told me. Since 2003, Beschta and his frequent co-author, the ecologist William Ripple, have published around 20 studies demonstrating the renaissance of Yellowstone’s vegetation, from cottonwood to willow to serviceberry. “Today, most aspen stands are on the trajectory of success,” Beschta said. “Personally, I’m not in a huge rush to push the system. I think it’s working.” Installing artificial dams to accelerate natural recovery, Beschta added, would be “an ecologically bankrupt idea.”

Beschta’s aversion to heavy-handed meddling is also why he wishes that Dan Tyers had never relocated beavers into the Northern Range. Wolves would have paved the way for the rodents’ eventual return, he insists. “He could’ve dumped a thousand beaver outside the park, and you’d still never have any in the Northern Range if the plants hadn’t recovered,” Beschta said. “The reality is there was no place for them before wolf reintroduction—zero.” To Beschta’s mind, the Yellowstone story proves that bringing back beavers throughout the West means keeping ungulates, both domestic and wild, in check—whether with more assertive cowboys or more abundant carnivores. “Until we resolve grazing issues, until we get functioning riparian plant communities that allow beaver to come in, we’re going in the wrong direction.”

I have spent more time tromping through Yellowstone National Park than I have just about anywhere else. And yet, until the summer of 2017, the park’s beavers were invisible to me.

The morning after our Elk Creek visit, Dan Kotter led me eight miles on foot up Slough Creek, a stream that horseshoes lazily through sweeping bison meadows on its way into the park from the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, to rectify my oversight. Twenty thousand years ago, the Pinedale Glaciation had gouged out this valley with a flick of its icy finger. Over millennia, Kotter said as we climbed, beavers aggraded the ice-carved trench into the lush grassland below us, capturing enough sediment in their ponds to fill a vertiginous V into a hospitable U. We could still make out the grass-covered shadows of ancient dams snaking across the damp meadows.

Now Slough Creek’s beaver population was again growing. When Doug Smith first surveyed the park’s beavers from the air in 1996, Slough Creek hadn’t supported a single colony; a decade later, it held nine. We met beaver sign everywhere: foraging canals slicing through damp floodplains, gnaw marks inscribed into small spruces, spindrifts of polished sticks washed ashore on point bars. “This place,” Kotter said, “is the beating heart of Northern Range beaver recovery.”

At last we stumbled upon shelter, a charmingly dilapidated cabin perched at Slough Creek’s confluence with a rollicking tributary called the Elk Tongue. No sooner had we dropped our packs than we were passed by a beaver coasting down Slough at high velocity, mocha head poking from the current. Later, we saw the same animal struggling back upstream at a much slower clip, riding high and ungainly, like a paddling golden retriever. It was the first time I’d seen a beaver look clumsy in his aquatic element. Kotter pointed out, though, that the creek’s flow was weakest at the surface, where it was diminished by friction with the air. Even awkward-seeming beaver behavior, I realized, conceals efficiency.

After dinner, we set out for some evening recon. Flooding had left Slough’s meadows soft and saturated; soon we were soaked to the shins. Baseball-sized boreal toads, a species that in many places breeds exclusively in beaver ponds, leaped to avoid our footfalls. Every quarter-mile a haystack-sized beaver lodge sprouted from the bank. Kotter cut across the floodplain to examine a massive dome with a freshly manicured roof. We knelt to examine tracks, a jumble of splayed hind feet and dainty front paws. Some of the impressions were no wider than a thumbprint. “I think there are kits in here,” Kotter whispered. We held our breath, and moments later faint burbles, uncannily like the cries of a human baby, rose from the lodge’s interior.

Evidently the parents did not appreciate our proximity, for the chirrups were followed by a resounding kerplunk, as though someone had thrown a flagstone into the stream. A glistening black head cut a wake through Slough Creek, whose glowing surface reflected the fiery sunset. The beaver swam toward us with startling boldness, tacking back and forth upstream like a sailboat battling a strong wind. He whacked his oar-like tail again, shattering the dusk and raising a plume of spray. He was brave, determined, selfless in the face of danger; I felt instantly guilty at causing him undue stress.

As we retreated through near-darkness to the cabin, bear spray at the ready, I realized this encounter represented something new to me. In my beaver-watching career, I had seen the adaptable animals flourishing in irrigation ditches, culverts, and drainage canals. But I’d never met one in a place so wild that I could gaze from valley wall to valley wall, upstream and down, without laying eyes on house, road, or artificial light. We have countless examples of how Castor canadensis uses and abuses human-built infrastructure, but precious few places where we can observe beavers interact with a full complement of native wildlife—wolves and elk, bison and boreal toads, cutthroat and cranes. Beavers are defined by their role as keystone species; the Greater Yellowstone is one of a handful of ecosystems where the arch remains intact.

Even so, there’s something fallacious about calling Yellowstone wild. Over the last 150 years, its denizens have been hardly more self-willed than the orcas at SeaWorld. Wolves were wiped out by one government agency, then reintroduced by another; elk were culled and subjected to firing squads the moment they crossed park boundaries. Bison still face hazing or slaughter when they summon the temerity to leave Yellowstone. Even the return of beavers, one of the park’s happiest stories, was abetted by a relocation program engineered by an idealistic Forest Service employee. Our wildest ecosystems are indelibly smudged with human fingerprints.

We woke the next morning from a sound night’s sleep in our Slough Creek cabin to find that rain had fallen and bejeweled the grass. After breakfast, Kotter cracked open a cabinet and unearthed a trove of old logbooks, scrawled with entries authored by visiting rangers and researchers. I sat on the wooden porch in the sun and leafed through 40 years of semi-legible jottings. Some were quotidian: “The outhouse door slams at the same moment every morning.” Others, dramatic: “Grizz print on door is a front pad and is 6 inches wide.” There, on November 30, 1988, was Dan Tyers, up Slough Creek to radio-collar moose: “Joys of early winter skiing—breaking trail; not as bad as trip last January.”

Wait a second—collaring moose? I’d been into Slough Creek half a dozen times over the years without once seeing hide or hair of Alces alces. As I paged through the logbooks, though, I discovered that both moose and elk had once been ubiquitous in Slough Creek. Nearly every journal entry mentioned encountering one or both species. In 1988: “Almost 200 elk seen between here and the Silver Tip ranch.” In 1989: “We’ve seen at least eight moose, many ducks, elk with new calves.” In 1990: “Saw elk in every meadow.”

While browsers apparently had the run of the place, beavers, I noticed, had been scarce. An entry from June 7, 1989, signed by one of Tyers’ assistants, told the tale: “Not good beaver habitat until you get to Frenchy’s meadows”—a bend far upstream. Now the species’ roles had reversed: Elk and moose had nearly vanished, and beavers had taken their place. The old logbooks might not qualify for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, but they still provided compelling testimony on behalf of an ecosystem restructured by trophic cascade.

The most powerful stories tend to be the simplest ones, the tales that can be cogently distilled into four-minute YouTube clips. Ecological truth, however, is harder to condense in a viral video. Much though we crave a unified field theory for Yellowstone National Park, we may instead be forced to settle for dozens of stories, each unique to its stream, each the product of a different permutation of topography, hydrology, and ecology. Yellowstone is larger than some European countries; it contains multitudes. There is room for waterways, like Slough Creek, that have been transformed by predators, and for others, like Elk Creek, that no number of wolfpacks could ever restore.

“The two most common words in ecology,” Kotter told me as we flipped through the musty logbooks, “are it depends.”

Toward the back of one journal, I came to an entry penned in 1991, signed by a mysterious M.B.—perhaps Mollie Beattie, former head of the Fish and Wildlife Service, who died of cancer in 1996, just a year after wolves were reintroduced. The log prattled on for a few sentences about meteorological conditions before wrapping up with a premonition that, in its wistful mix of hope and yearning, hit me with the force of a line from A Sand County Almanac. “All this place needs is a pack of wolves to serenade us to sleep,” M.B. had written, four years before the carnivores’ return. “We’re working on it!”

This excerpt is from Ben Goldfarb’s new book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

You May Also Like

Google Snake Game: A Classic Arcade Experience

March 23, 2025

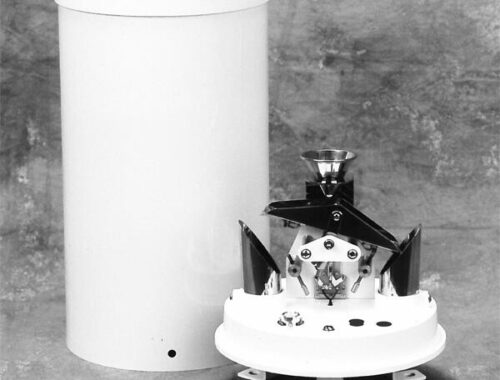

10 Practical Applications of Rain Gauges in Everyday Life

March 20, 2025