In Breakup with Boy Scouts, It’s Mormons Who Lose

>

After over a century together, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and the Boy Scouts of America are calling it quits, effective December 31, 2019. What does that mean for the country’s largest outdoors program? I spent the last two days trying to figure that out.

To understand the significance of all this, you first have to understand how intertwined the two organizations currently are. Scouts in LDS troops currently make up about 20 percent of BSA membership. Historically, that number has reached as high as one-third. That’s because the church enrolls all its boys in Cub Scouts when they turn eight, then in Boy Scouts once they’re 11. The BSA has historically been the official youth development program for boys in the Mormon church, but it will be replaced in 2020 by a new program the church is developing that will place a greater emphasis on religion, rather than outdoor experiences. Church members will be free to participate in scouts, but they will no longer be compelled to do so.

The way the BSA organizes its individual troops allows for unique arrangements like that, serving local needs. The national organization sets direction, then chartering organizations—churches, community centers, and such—sponsor individual troops that are naturally attuned to the needs of local communities. Boys involved in Scouts through a Mormon church in rural Utah work on the same programs, with the same goals as boys participating in scouts through a YMCA in the Bronx, but the culture within those two example troops will obviously differ.

This approach has enabled the Scouts to effectively serve the diverse needs of kids across the country for the last 108 years, but it’s also occasionally led to tension with the LDS church. At times, the BSA has pushed the church to be more progressive. In 1978, the Boy Scouts forced the church to allow African-Americans into the priesthood for the first time. (That was the topic of an article I wrote in 2015.) Adult Scout leaders from outside the church have told me that summer camps and other scout events appeared to be the first time that many Mormon boys had encountered people from other faiths, races, and cultural backgrounds.

Yet the influence of LDS is part of the reason why the BSA has maintained such conservative practices for so long, according to multiple people I interviewed, who asked to remain anonymous to avoid ruffling the feathers of either the BSA or the church. It wasn’t until 2013 and 2015 that the BSA formally accepted both gay boys and adults as members, respectively. (When I requested comment from the BSA, the spokesperson referred me to the joint statement with the LDS church.) But when up to a third of your membership—and your revenue—comes from a single, conservative organization (the Mormon church still considers homosexuality a sin, and does not admit practicing homosexuals into its priesthood, it's not shocking that you could be forced to take its interests into account.

This recent break has been a long time coming.In 2015, when the BSA began accepting gay adult leaders, the Mormon church objected and threatened to withdraw its support. A compromise allowing individual troops to set their own adult volunteer policies was reached that year, but the church still began development on the new youth development program that’s launching in 2020. In January 2017, the BSA began accepting transgender boys as members. In May of that year, the Mormons announced that they would begin withdrawing from the BSA’s older teen programs. Then, in October, the BSA announced that it would begin allowing girls. Last Wednesday, it announced that it was dropping the gender from the name of its teen program, changing it from Boy Scouts to Scouts BSA. One week later, the Mormons announced their withdrawal from Scouting.

“This is a sad day for Scouting,” Justin Wilson, the executive director of Scouts for Equality, told me over the phone yesterday. That answer surprised me. Wilson leads an organization that has campaigned heavily for the BSA to become more inclusive. I was expecting him to celebrate the official end of the church’s sway over Scouting, but instead he mourned the loss of the organization’s influence on Mormon children. “The more kids who benefit from Scouting, the better,” he says.

Everyone I spoke with while writing this article expressed a strong sentiment that it’s Mormon youth who stand the most to lose. While they’ll still be able to chose to participate in Scouting, and work toward the Eagle rank, its inevitable that fewer of them will do so. It remains to be seen what the church’s own program will offer its kids. “High-level Scouting creates opportunity, and with opportunity comes a chance at success,” says Sydney Ireland, who fought to convince the BSA to allow women Scouts.

The breakup is going to hurt the BSA financially. The Mormon church currently enrolls nearly 460,000 Scouts in the BSA, and each scout pays $33 per year for membership—a contribution from the church of about $15 million per year. Some of the adult Scout leaders I spoke to predicted an increase in membership fees to help offset that lost revenue. That said, no one had any fears for the BSA’s future. “The BSA is doing just fine financially,” says Wilson. “They never have a problem finding plenty of donors.” (The BSA received $65 million in charitable donations in 2016.)

The BSA still requires both boys and adult volunteers to believe in God. Devout atheists need not apply. Will the withdrawal of the Mormon church from Scouting lead to change in that long-held policy?

“We obviously want to work toward a future in which religion is not a prerequisite for people to participate in Scouting,” says Wilson, citing his belief that Scouting should benefit as many kids as possible.

Scouts doesn’t dictate which god you have to believe in, just that you do need to believe in one. Anecdotally, I’ve seen more and more parents voice this as a reason why they haven’t encouraged their kids to participate in Scouting. In my own experience, it creates a dilemma for non-religious Scouts. The Scout Law requires Scouts to tell the truth, yet as an atheist, I lied through omission both when I attained the Eagle rank and when I became an Assistant Scoutmaster as an adult. I doubt I’m the only otherwise proud Eagle Scout who’s been forced to do that.

“There’s still a lot of strong religious influence within the BSA, and a lot of support for the requirement,” says Cate Readling, an adult BSA volunteer in Chicago who has three sons in the Scouts. Many chartering organizations within the BSA are churches, and many will likely still be LDS churches, even after 2020. But none of them represent a voting block compromising 20 percent of the organization, or speak from such a unified platform.

You May Also Like

Google Snake Game: A Classic Arcade Experience

March 23, 2025

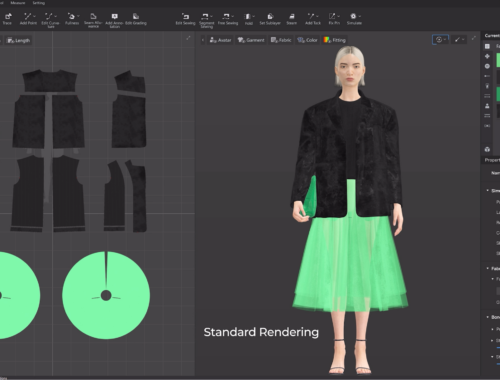

AI in Fashion: Transforming Design, Shopping, and Sustainability for the Future

March 1, 2025